Lieutenant Tony Sangster RN, the Gunnery and Correspondence

Officer on HMS Venomous, wrote a 180 page unpublished memoir of his service in the

Royal Navy. He joined Venomous in March 1942 after its refit following the collision with HMS Keppel and his memoir includes a description of convoy PQ.15 to Murmansk in northern Russia, the sinking of HMS Eagle

while escorting a convoy to relieve the besieged island of Malta and

the events of the night of the 11 - 12 November 1942 when Hecla sank.

Lieutenant Tony Sangster RN, the Gunnery and Correspondence

Officer on HMS Venomous, wrote a 180 page unpublished memoir of his service in the

Royal Navy. He joined Venomous in March 1942 after its refit following the collision with HMS Keppel and his memoir includes a description of convoy PQ.15 to Murmansk in northern Russia, the sinking of HMS Eagle

while escorting a convoy to relieve the besieged island of Malta and

the events of the night of the 11 - 12 November 1942 when Hecla sank.

Tony

Sangster was born in Kandy, the ancient capital of Ceylon, in 1921

where his father was a tea planter. He was sent to prep school,

Stubbington House School ("the cradle of the Navy") in Fareham,

Hampshire, as a child of seven and farmed out to relatives during the

school holidays. His older brother, known as Derek Sangster

(but christened Anthony Trevor), had chosen the Navy as his career and

Tony Sangster followed him. They were both Cadet Captains at the Royal Navy College,

Dartmouth, served throughout the war and retired as Lieutenant Commanders in the 1950s.

Tony Sangster went to Dartmouth in 1934 and on leaving in 1938 joined the cruiser, HMS Vindictive, for his sea training. When war was declared he was serving as a Midshipman on the battleship, HMS Warspite. After a promotion course at HMS Victory, Portsmouth, and further training he was posted to the cruiser, HMS York, at Singapore.

On the 11 March 1941 he embarked at Liverpool on the SS Britannia, a passenger liner adapted for use as a troop carrier, bound for Bombay via Freetown and Durban. The Britannia was attacked and sunk by the German commerce raider Thor near the Cape Verde Islands on the 24 March and the passengers and crew took to the lifeboats. Tony Sangster's lifeboat was waterlogged with only the stem and stern above water. There were only nine survivors out of the fifty four in his lifeboat when they were picked up after five days by the neutral Spanish ship, Cabo de Hornos. They were landed at Tenerife in the Canary Islands where the British Consul negotiated with the Captain General of Canarias that they would be treated as "Distressed British Seamen" and confined in a hotel at Santa Cruz which constituted an "internment camp". They were under parole and accountable to the Consul and their Senior Naval Officer. After four months the Consul was able to arrange for them to be released at Gibraltar and he was posted to the destroyer HMS Montrose as Sub Lt Navy Signals in September 1941.

He made an interesting comparison between Montrose and Venomous which is worth quoting here:

"Venomous was an extraordinary ship. She behaved very well in rough weather, and was quite unlike Montrose which being 30 feet longer was really beautiful with two matched funnels. However, 'andsome is as 'andsome does, because although Montrose with her beautifully flared bow and her balanced silhouette looked so nice she was an absolute pig at sea. She had so much top weight that she heeled crazily under large rudder, and rolled all over the place. Worse still, when she pitched, her after end used to whip up and down and you could not keep your feet on the deck. You really had the impression of being on a diving spring board."

He was plagued with persistent inner ear and throat infections, the lingering after effects of his time in the lifeboat, and was eventually invalided out of Montrose. He joined HMS Venomous

in time for Arctic Convoy PQ.15 to Murmansk in Northern Russia which is

described in his unpublished memoir. This was followed by escorting

Convoy WS.21S to relieve the besieged island of Malta when HMS Eagle was sunk and Venomous took several hundred survivors back to Gib., a low key "rehearsal" for the dramatic events of the 11 - 12 November 1942.

Tony Sangster's account of what happened when Hecla was torpedoed begins as Convoy KX.4A assembled off Gourack at the mouth of the Clyde.

Venomous

left Gourack after fond farewells to “Two Ton Tess” [probably the

"torpedo" with the one ton depth charge fitted in the No. 1 torpedo tube during

the refit at Troon; also known as the 'brute', it was never used], and

a very special

Patricia, in the Bay Hotel the previous night. Usual convoy we

supposed, but no, off the Mull of Kintyre where all the elements of the

convoy assembled, there were passenger ships, fast liners with troops

crowding them.

Venomous

left Gourack after fond farewells to “Two Ton Tess” [probably the

"torpedo" with the one ton depth charge fitted in the No. 1 torpedo tube during

the refit at Troon; also known as the 'brute', it was never used], and

a very special

Patricia, in the Bay Hotel the previous night. Usual convoy we

supposed, but no, off the Mull of Kintyre where all the elements of the

convoy assembled, there were passenger ships, fast liners with troops

crowding them.

The Captain, Commander Falcon-Steward, was I think Senior Officer of

the Escort and there was the usual extended climax of signaling by

lamp and flag to the Commodore, and the escorts to arrange ourselves in

the appropriate pattern. After all the usual grind of protecting trade,

at last it looked as if we were going on the offensive!

The general direction of advance was west south-west, way, way out into

the Atlantic. October 1942 – were we going to attack the West Indies or

South America? At last we turned South, and later on South East for

good historic approaches to the Mediterranean where Nelson had taught

the world a lesson which still stirs my heart today in 1981.

They had a Royal Fleet Auxiliary tanker in the convoy from which all

the escorts fueled in turn in the last stage before the Straits of

Gibraltar.

At dead of night the great ships passed through these straits, and more

escorts joined, and Venomous was detached to steam in the reverse

direction westwards. Meanwhile, the great merchant ships, the real

might of Great Britain, went eastward into the Med., with those brown

job soldiery on board. They were the second wave of Torch, the code name for the North African landings.

Convoy Escorts for HMS Hecla and HMS Vindictive

The next day found us with Marne,

one of the really chunky destroyers of L&M Classes in line abreast

making SW out of sight of the African coast at 15 knots. Security was

so strict that even the officers of the Watch knew not what to expect.

Two days out of the Straits:

“Captain, Sir!”

“Yes, ”

“Two ships on the horizon at Red one oh, mast only in sight.”

Marne’s ten-inch signal lamp proved that they were equally alert and aware of the sightings.

And so in half an hour we met our convoy: Vindictive (my cadet training cruiser four years ago, but now converted into a submarine depot ship) and Hecla, sister ship of Tyne, built as a destroyer depot ship. Maximum speed of convoy 15 knots, albeit Vindictive could do 24.

Venomous took the starboard wing position, and Marne

the port wing and, we turned back towards the Straits of Gib., or in

naval parlance – “the gut”. Conventional zig-zag, escort conforming.

The Asdic Operator reports a contact ...

I had the first watch that night (2000-2400) and about 2315 the Asdic

sonar operator [George Wilson,

the 19 year old Asdic operator, who reported to Warrant Officer

"Jimmy" Button, the Anti-submarine, Bo'sun] reported a contact Green 60

(60 degrees on the starboard

bow)

“Starboard twenty, set one depth charge pattern to 200 feet.”

“Captain, Sir,” (down the voice pipe) “Asdic contact altering towards!”

Well, we did not drop any depth charges because contact faded and

disappeared, and ‘non submarine’ was eventually classified. So the

Captain hoisted up the speed to 24 knots and withdrew the Asdic dome in

order to regain station on our convoy, which had by now got ahead of us

by about 8 miles.

The depth charges were reset to safe and we tried to interpret the

radar reports of surface echoes. What we had expected to see was … and

because of wireless silence and the total silence of our radio

telephone on 4140X/08, it looked all wrong. As we got close we could

sight the nearest ship and she was obviously stopped. Fearing the worst

the Captain reduced to 15 knots, lowered the Asdic dome and ordered

Action Stations.

Hunting the U-boat

In due course shaded flashing lights established what had happened.

Hecla had been hit by two torpedoes on the starboard side and was

stopped in danger of sinking. Marne had closed her and was about to put her bow alongside to take off survivors. Vindictive had left independently at her 24 knots.

The old Venomous was coming back into the picture. We had just started a square mile search of 2mile sides when our Asdic operator yelled:

“Torpedo, torpedo, Green 40 to 70” (40 – 70 degrees on starboard bow)

“Hard a starboard, steady on 110,” ordered the Captain quite quietly.

And on the Asdic loudspeaker dwarfing the ‘ping’ of our own

transmission everyone could hear the tube-train kind of roar picked up

from torpedoes. There was a horrible thud in our own ears, and the

loudspeaker roar decreased, there was another horrible thud and the

roar ceased altogether. Marne’s stern had been blown off and the other torpedo had hit Hecla again.

Immediately, a shaded blue heather (?) lamp started flashing us from Marne, “U-boat my starboard quarter!” “Hard a starboard – full ahead both engines,” and off we went cutting past Marne’s

stern. After a minute with no report from radar, the Captain cried,

“Fire a Snowflake.” With a swish the rocket ascended and far above the

magnesium burst into light and floated down on its parachute and there

at Red 10 was a submarine powering away on the surface – 400 yards

away.

At full ahead Venomous had

sunk her stern as her screws bit into the water. There were lots more

orders. B gun (4.7 inches) got off 2 rounds, whose charges were

supposed to be non-flash for night-fighting, but we on the bridge were

all blinded. The port oerlikon opened up and tracer crowded round

the coning tower of the enemy. I was adding to the din being the

Gunnery Officer controlling “B” Gun. By the next time a snowflake went

up, there was no submarine, just our bow wave spoiling the calm dark

sea.

And then we saw it, just near our bow, the still-bubbling swirl of a submarine’s dive. The anti-submarine Bo’sun broadcast:

“Stand by emergency pattern – shallow setting – Fire One! Two! Three!”

Venomous careered on and immediately the mine explosions were over the Captain reduced to 15 knots so as to use his Asdic.

We never got contact with the Asdic. Square searches followed around

the last known spit of ‘swirl’ which had been marked on the clock-work

plot in the chart house. We went on searching for an hour and a half.

Hecla had meanwhile sunk and we kept on hearing shouts from the water

and the occasional torch was seen. We stayed at action stations all

night, and reduced to two watch defence stations at dawn. There was no

sense in exhausting everyone and fighters must eat!

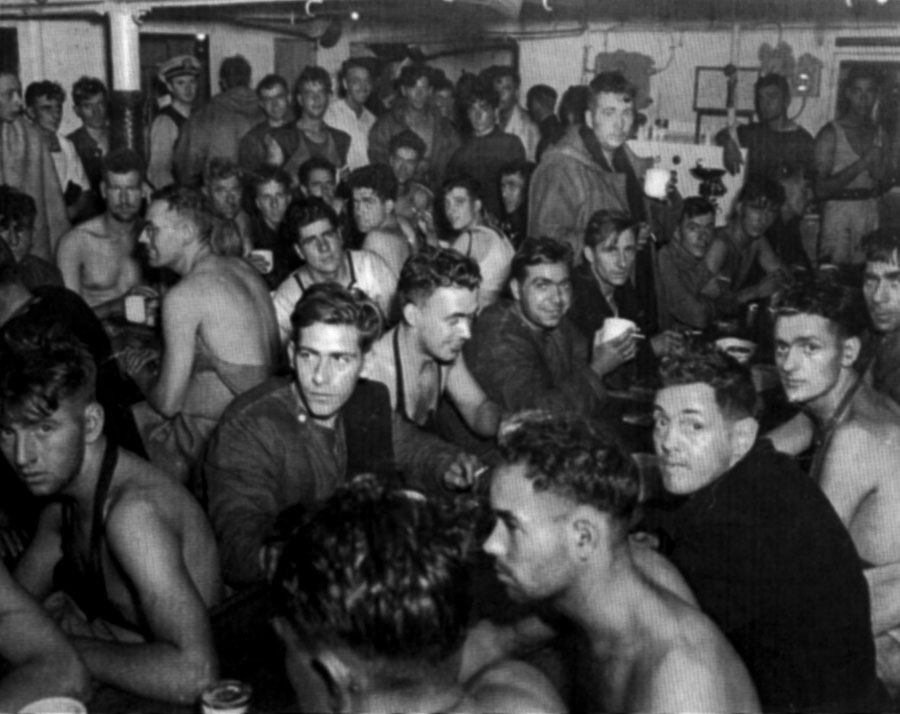

Rescuing survivors

Meanwhile Marne was rolling in the swell, her stern amputated by a torpedo. You could even see her 4.5-inch shell cases in the after magazine being lapped by the sea.

Could Venomous reach Casablanca?

After all the emergencies, Venomous

was desperately short of fuel and the Captain was in a quandary. He had

505 survivors on board. One of our newest destroyers was a floating log

with its propellers removed. Submarines might still be around. We tried

to take fuel from Marne but

the swell prevented this. At about 4 pm we sighted a frigate and a

corvette, and the Captain called them up by light, and ordered one to

take Marne in tow under the

escort of the other. Before they arrived the Captain had to move

Venomous away in the direction of Casablanca, at the most economical

speed on one boiler only, of 11 knots. The least cheerful chap in the

Ward Room was the Chief (Warrant Engineer). He by all the gauges had no

fuel left at all, but yet had to coax 120 miles of steaming to

Casablanca. But this breed of warrant engineers is remarkably

resourceful. When a fuel oil pump fails to suck from a fuel tank, there

is a residue left because the suction end of the pipe is a few inches

off the lowest part of the tank. So Chief got his Chief Stoker to

organise the Stokers to go down through manholes, with face masks to

supply fresh air, and they handed up bucket by bucket all the residues

and poured them all into just one tank. A heroic effort. Fuel oil is

like filthy treacle and the fumes are dangerous. [Warrant Engineer Horace Rance Pead RN was MID for his efforts that day]

NOTE

From

this point onwards Tony Sangster's memory of events is less reliable.

The survivors who died from their wounds after rescue were buried at

sea after leaving Casablanca while en route to Gibraltar. Lt Cdr "Harry"

Alexander RN, the most senior survivor to be rescued by Venomous, was

photographed reading the prayers at the burial. On arrival at

Casablanca Venomous berthed alongside USS Augusta and it was here that

the survivors were kitted out with US Navy clothing and given a hot

meal before rejoining Venomous

which later moored alongside a USN flattop where the survivors spent

the night sleeping in the aircraft hangers. Tony Sangster gives its

name as USS Boxer but it is thought that he was mistaken and it was

actually USS Chenango. These errors have not been corrected.

Meanwhile we had to bury three dead at sea, wounded survivors who had

not recovered. The prayers for such burials are in your prayer book.

Nest morning we entered the erstwhile Vichy France controlled harbour

of Casablanca. We berthed ourselves at a jetty opposite the Escort

Carrier USS Boxer. Except for the usual piped salute of the ‘still’ from both of us there was really at first no acknowledgment from Boxer of our survivors. Then an officer arrived to say “Please send your survivors over 20 at a time, every 20 minutes.” Boxer’s

Commander had organised a line of goodies on the scale of one minute

per man. Issue of new jean sailor’s kit, shaver, thank you very much,

and off you go back. I went over to witness it, and it really seemed

like a Henry Ford production line, but much more humorous on both sides

of the counter.

Having fuelled from Boxer, I think, Venomous made her way back to Gib., and said goodbye to our passengers. I wonder how many of those will read this little story.

What I never mentioned was that Vindictive

pressed on with her 24 knots and reached Algiers unescorted. Sadly I

gather that her Captain got a very cold reception from one Admiral, who

considered he had fled from the centre of action.

Aftermath

Herbert James Brown Button did

not live. After his rescue efforts he was exhausted and stayed in the

bunk next to mine. After several hours he started groaning and seemed

to be in a coma so I got our Surgeon, Lt Maxwell to examine him.

We put into Algiers and he was lowered in a special stretcher and then

taken ashore and by ambulance to hospital, and death by meningitis; a

great sadness to us all, and certainly not the way to end a story.

I never knew whether our depth charges had sunk the U-boat, but it

often struck me as strange that the U-boat did not attack the

stationary Marne the next day.

In 1980 I got this information from the Ministry of Defence, Naval Historical Branch.

Being Correspondence Officer I helped to draft and finally typed the

Captain’s report and we certainly did not claim even a ‘possible’ kill.

*******

Midshipman Stephen Barney joined Venomous soon after Hecla sank and had a great liking for Tony Sangster, his "oppo".

He took over from him as Correspondence Officer and recalled that before the

handover Sangster went to immense trouble to see that the ratings were

compensated for the clothes and blankets they had willingly given the

survivors of HMS Hecla.

Cdr H.W. Falcon-Steward RN left in December and was succeeded as CO by the flamboyant Cdr

D.H. Maitland-Makgill-Crichton RN but he did not stay long and was

replaced by a very different CO, the modest unassuming Lt Henry D.

Durell RN, who quickly won the affection of his fellow officers.

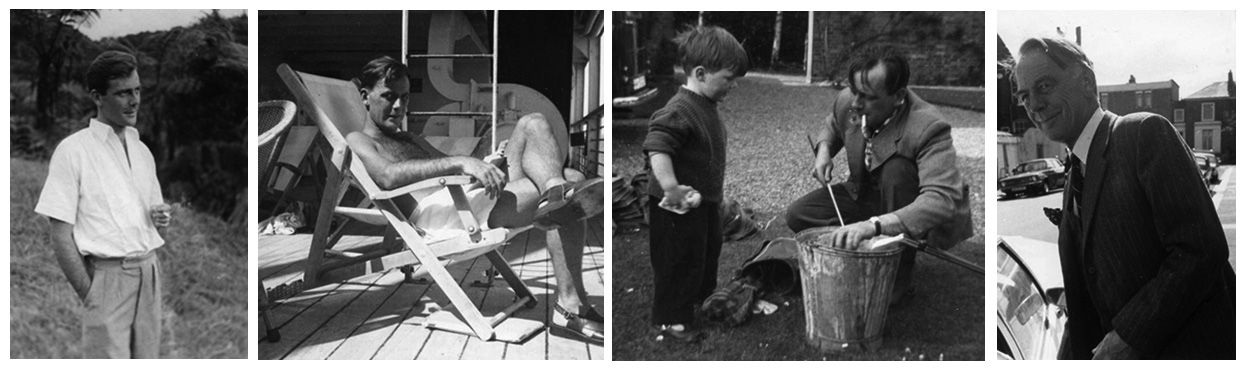

Stephen Barney recalled one characteristic incident when Tony Sangster

shaved off his beard and entered the Wardroom pretending to be an

officer from another ship. Durell went along with the legpull, made the

visiting officer welcome and offered him a drink. Tony Sangster

described Durell as "a man of great charm, great professional

competence, and an uproarious sense of humour which made him a great

debunker of the ridiculous" and told an amusing story

which illustrated these characteristics in his memoir.

Cdr H.W. Falcon-Steward RN left in December and was succeeded as CO by the flamboyant Cdr

D.H. Maitland-Makgill-Crichton RN but he did not stay long and was

replaced by a very different CO, the modest unassuming Lt Henry D.

Durell RN, who quickly won the affection of his fellow officers.

Stephen Barney recalled one characteristic incident when Tony Sangster

shaved off his beard and entered the Wardroom pretending to be an

officer from another ship. Durell went along with the legpull, made the

visiting officer welcome and offered him a drink. Tony Sangster

described Durell as "a man of great charm, great professional

competence, and an uproarious sense of humour which made him a great

debunker of the ridiculous" and told an amusing story

which illustrated these characteristics in his memoir.

Tony

Sangster's memoir continues with a description of a curious incident of

"spontaneous combustion" off Cape Bon while escorting the first west to

east convoy from Gib to Alex since 1941 and then the escort of the

"second wave convoy" to the landings near Augusta on the south east

corner of Sicily in July 1943. After the Sicily landings Venomous

returned to the Clyde for an urgent refit and Tony Sangster was

"relieved and sent on leave to await appointment". He traveled to the

USA on the 51,000 ton Cunard liner Aquitania, converted into a troopship, to take command of HMS Loring,

a diesel-electric Captain Class Frigate, while it was under

construction in the Boston Naval Yard. After commissioning he served as

First Lieutenant to Lt J Ogilvy RN.

In November 1944 Tony Sangster was posted to the Hunt Class destroyer, HMS Blackmore, as First Lieutenant while it was under refit at Sheerness before it left for the Far East. In April 1943 HMS Blackmore

arrived at Trincomalee in Ceylon, where he was born and met his future wife, Ellen Mawdsley ("Lell") Paterson, the 27 year old

widow of a fighter pilot killed on patrol over Dunkirk in 1940, a member of the the army nursing corps, the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY). HMS Blackmore was deployed as a weather ship in the Andaman islands during the landings at Rangoon (Operation Dracula) in May and in preparation for the cancelled landings in Malaya (Operation Zipper).

As a career officer Tony Sangster remained in the Navy after the war ended. He remet and married Lell Paterson on 15 April 1946 while serving as Drafting Officer at FOMAS in Singapore and in August 1948 was lent to the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and took passage to Australia with his wife on the Stratheden. He served with the RAN for two years, on HMAS Leeuwin (1948-9) and during the Korean War as Lt Cdr A.d'E. T. Sangster RN on HMAS Shoalhaven (1949-50) based in Japan. He returned to Britain in December 1950 and retired from the Royal Navy in 1956 when he was 35

Their

two sons, Michael and Charles Sangster, were born in Britain and Tony

Sangster started a new career at John Summers steel works on Deeside and the family lived in Tarporley, Cheshire. He remained with John Summers until his retirement and died in March

1992. His widow died peacefully in the family home in February 2001 aged 103.

Officers serving on on HMS Venomous

on the 12 November 1942

A complete list of the officers and men serving on HMS Venomous during this action can be seen by clicking on the link

The

list has been compiled by TNT Data Services under contract to the

Ministry of Defence based on the seventy year old hand written

Pay and Victualing Ledgers kept by the Admiralty.

Read Lt Cdr H.C.R.Alexander' RN's "View from the Bridge" of HMS Hecla