The officers commanding HMS Hecla, HMS Marne, HMS Venomous and HMS Vindictive,

the other destroyer depot ship being escorted to the invasion beaches

in north Africa were required to write Reports of Proceedings giving

their account of the loss of Hecla. These have all been located and with the Report of the ASW Division, the U-Boat Assessment Committee and

Admiral Cunningham's report on the disaster (sometimes casually

dismissed as "the Hecla incident") formed the basis for the analysis by Captain John Rodgaard USN in A Hard Fought Ship.

The officers commanding HMS Hecla, HMS Marne, HMS Venomous and HMS Vindictive,

the other destroyer depot ship being escorted to the invasion beaches

in north Africa were required to write Reports of Proceedings giving

their account of the loss of Hecla. These have all been located and with the Report of the ASW Division, the U-Boat Assessment Committee and

Admiral Cunningham's report on the disaster (sometimes casually

dismissed as "the Hecla incident") formed the basis for the analysis by Captain John Rodgaard USN in A Hard Fought Ship.

The Freedom of the Veld

I

had no ambition to enjoy a five-month holiday and applied to the

Admirals staff for an appointment, which would help the prosecution of

the war. At first the staff turned down my request but later relented

and that same evening I received a signal appointing me to the staff of

Brigadier Poole, the Fortress commander in Capetown, who had just

returned from Torbruk. Four very happy months of planning ensued

and I may even have contributed to the safety of Capetown water supply

since I arranged for it to be assured by sentries armed with

assegais. At the end of those four months I took a weeks leave

and traveled to Mooresburgh by train to spend the night with the

parents of one of my fellow officers who provided me with a pony and a

small sack of oats. But before sending me off next morning they had

arranged a treat for me, namely a tea fight with General Smuts. This

was a simple affair on the stoep and I felt greatly honoured. The great

man was very kind but of course we mostly talked of family matters.

Next day I set off early in a Northerly direction aiming to cover some

30 miles a day but the farmers en-route were all so friendly and

hospitable that it was really impossible to disappoint them. Maybe the

loop I traveled only represented a total of possibly 140 miles -

mostly marginal land and lacking water. The last farm I stayed in was

really primitive and when I asked for the bathroom my host waved his

arms and conferred the Freedom of the Veld upon me. He spoke good

English, but none of his seven sons were bilingual. On my return to

Capetown I found a large box of chocolates with a picture of a horseman

so posted it to my host and sons. Within a few days I received a

garrulous acknowledgment, seven pages of scolding, "why do you send

present", etc., etc, but ending up with "now my seven sons are all

going to learn English so that they can speak with you when you come

back."

People told me I should never have gone into that barren corner of Western Cape Province, because the people were Osseva Brandwoel,

subversive elements. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

They were all good kind people; simple yes, but high principled and law

abiding.

The following weeks we were all very busy on board sorting out the

replacement equipment and getting to know the reconstituted messes

- and then the great day came and we sailed in convoy again but

retracing our steps, for the European war was just round the corner and

N. Africa our first objective.

"We should alter course 60 degrees to Port."

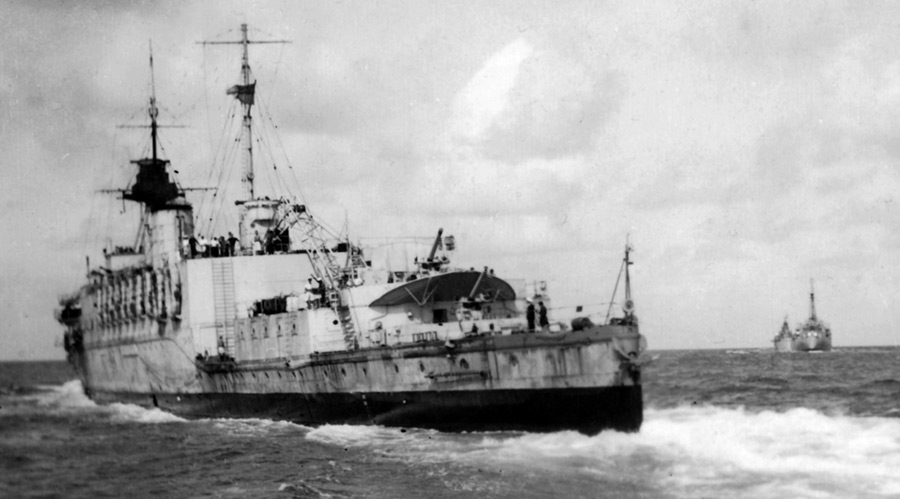

The officers and crew of HMS Hecla are photographed on deck just days before their ship was torpedoed by U-515

Courtesy of Steve Davis, the stepson of Tom Davis, the photographer

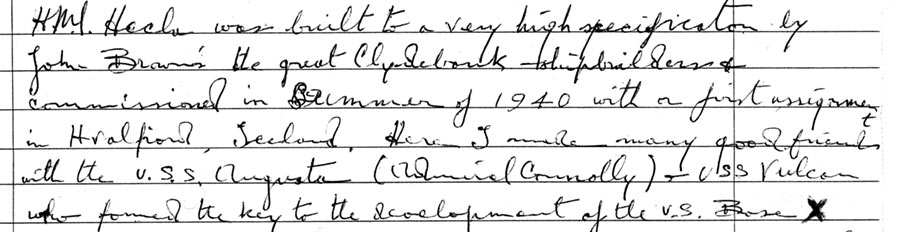

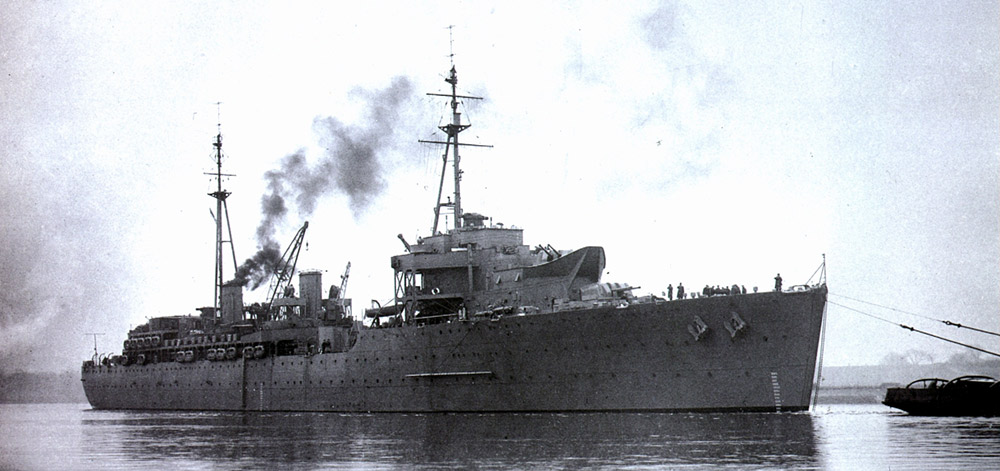

The last photographs of HMS Hecla (top) and HMS Vindictive (bottom) before they detached from Convoy CF.7A and headed for Gibraltar

Photographed by Tom Davis, a young RNVR rating on the destroyer escort HMS Active

At Freetown HMS Vindictive

joined us for the next leg to Gibraltar and as her Captain was the

senior officer he took command when our small group was detached, some

500 miles SW of Gibraltar. Ships were disposed as follows: HMS Vindictive leading, HMS Hecla stationed two and a half cables astern; the escorting destroyers were HMS Venomous stationed on the starboard bow and HMS Marne on the port bow. The latter was a very modern ship with plenty of fuel but Venomous probably had insufficient fuel remaining

to get her to Gibraltar, the majority of this vintage class had been

mothballed into maintenance reserve some fifteen years earlier.

At 3 pm on the 11 November we received an aircraft report of a U-Boat

lying dead on our route and after plotting it on the chart I reported

to my Captain that we would be meeting it at 11 pm. During the next two

hours of daylight both my Captain and I became increasingly perturbed

at the Senior Officer's singular inactivity and my Captain asked me for

my opinion. I was ready for this and replied without hesitation,

"We should alter course 60 degrees to Port." The chief Yeoman then came

up with a brilliant suggestion, "Shall we B the aircraft report ?" In

plain English, "Have you received the submarine report?".

This seemed to sting Vindictive

into some sort of action but, alas, quite useless. A six degree

alteration of course taken three hours earlier would have been adequate

but taken at 6 pm within five hours of our encounter it merely moved

our approach track some seven miles and with a full high moon we would

be visible at twice that distance. By this time it was dark and we were

precluded from making any lamp signals towards the senior officer,

knowing any submarine lying on our route might pick them up. If we

could have signalled I would have liked at this time to signal "Suggest

zigzag may be started at 2200" to give maximum protection under

these extremely adverse conditions but of course the time for signals

was past and remembering the Venomous'

fuel problem I kept my counsel. In this I was grievously wrong, it

would not have mattered in the least if we had been obliged to tow Venomous

the last 100 miles into Gibraltar. Those waters were excellently

patrolled and U-Boats had plenty of targets farther afield without

looking for trouble around one of our finest bases.

"Every man for himself"

Disaster

came punctually at 11 pm when we were steaming NE for Gibraltar about

400 miles away. The sickening crash and tearing steel from a first

torpedo on our starboard side immobilised our engines and electricity

failure prevented our hoisting out any powerboats. After quite a short

time Vindictive sent back HMS Marne

to pick up survivors but unfortunately her Captain was too young to

remember the Hogue Aboukir disaster of the first world war and stopped

within swimming range before making a sweep for the U-Boat.

In Hecla

the starboard list was easily corrected but, alas, the U-Boat then

fired a torpedo into our port quarter. The Captain seeing the track

said quite cheerfully "That is going to miss astern". I could not

agree but kept silent. He was new to the ship and am sure did not

realise the torpedo was far ahead of its bubble track and its speed

probably 40 knots. Anyway the torpedo blew up abreast our mainmast on

our port quarter and was probably responsible for killing our entire

cypher staff including my splendid Gyro Compass Artificer. He thought

one of our two gyros could be got going again but I told him I did not

need either as I had a perfectly good magnetic; but he was so keen that

I reluctantly let him go down for five minutes - the last torpedo must

have struck near where he was working. After a very few minutes a third

torpedo was audible and the bubble

track seen coming straight towards our bridge. The explosion sent up a

column of water like a giant fire hose and gave us all a sound blessing

a second time, coming down. The situation then looked hopeless and

orders were given for "Abandon ship stations" and finally, "Every man

for himself".

As it had not been possible to hoist out our boats and both sea boats

were damaged and most Carley Floats had been damaged or dropped from

their brackets, I thought at first to take a large bridge stool to have

something buoyant to hold onto. Then I changed my mind and picked up my

mattress from my sea cabin and tried to get down to the upper deck with

the ship listing over some 45 degrees. This delay lost me the rest of

the bridge party who had gone aft. As I reached the upper deck level

the ship lurched to a 90 degrees list and while I was getting over the

berthing wires lugging my mattress, a torpedo struck HMS Marne

in the stern which blew up in the most spectacular display of

fireworks, depth charges and all. I remember thinking this destroyer

was probably our last chance of survival as she would now be

immobilised and ripe for just one more torpedo; I also thought "What a

pity I'll never be able to tell anyone what a superb display of

fireworks I’ve seen".

I then heard a young Lieutenant called Steavenson, asking for help from the

water so I threw down a ropes end from the seaboats falls and hauled

him up to where I was standing on the ship's side, just above the

rolling keel. He was very exhausted and I offered to share my

mattress when the moment came. The ship was soon almost exactly

180 degrees over but very deep in the water, but much rumbling going on

inside as enormous weights shifted and took charge. Then suddenly a

wave appeared to come up from the stern, we put my mattress on the

crest and were wafted as if by a magic carpet towards the bows. I

realised afterwards that the wave of course was not an ordinary wave

but the result of the ship sliding down by the stern with the

upending. And so we found ourselves swimming with this monstrous

fore-end of the ship towering above us. We could never have swum

clear if the forepeak had broken off in our direction, but no, John

Brown had built as good a ship as ever, and even the immense repairs

carried out in Simonstown remained faithful to the original.

Almost immediately the mattress became water logged and we abandoned it

to search for something better.

The moon which had betrayed us in the first instance had set by now but

the sky was clear and one could see quite a distance and hear the vain

despairing cries of various sailors calling for their mates. The first

useful object we found was a launch's towing bollard, not ideal being

too thick to hold but still better than nothing. Then I noted a curious

dome-like dark object some fifty yards away and suggested we might go

over to look at it, but Steavenson said he was too exhausted. So I went

alone and to my bitter disappointment found it was an awning with an

air bubble holding it up. Anywhere I put some weight simply went down

and let more air out on the far side. So I went slowly back to

Steavenson, rather crestfallen, conserving my strength knowing we were more than a hundred

miles from the west coast of Africa.

I

settled down to estimate the time by watching the slow, oh so slow,

movement of Sirius. After some three hours, possibly at 4 am, a most

extraordinary splash and crash

coming from about a hundred yards away worried me for a moment,

thinking it might be the submarine surfacing to collect evidence of its

successful exploit. My next thought was could it possibly be a whale?

If so would we finish up like Jonah? But when the object did not move I

suggested we should swim over and investigate. Stevaenson again said he

was too tired. When I reached the object I found it was one of Hecla's 25 ft

motorboats - badly mangled but still floating awash to the gunwhales -

but non the less extremely attractive. So I again swam back to young

Steavenson and brought him to the boat and had no difficulty in getting

both of us sitting on the gunnels. After a short breather I decided we might improve our chances if we bailed out the

water, so carried out an underwater search for a bailer. This was

made easier as I had discarded my short gumboots at some time during my

various explorations. It also proved unfortunate, however, because the

bottom of the boat was littered with broken glass from the cabin

windows and my socks as well as my feet were cut before, at last, I

found a paint pot and started bailing.

This did not last long because I quickly tired, finding the pot

incredibly heavy and only removing about a cupful of water.

During the short rest my hand holding the precious pot happened to go

into the pot revealing the reason for its inefficiencies, namely that

it was still three quarters full of paint! I was tired and that is my

only excuse for doing a really stupid thing, namely flinging most of

the paint over the side. It was only after I had cleaned out the pot

that I realised my folly, thinking of the necessity of blocking anymore

water coming into the boat I had noted that the engine exhaust pipe was

broken and letting water flow into the boat. I had decided to block its

passage by stuffing it with my pyjamas which I had hurriedly put into

my raincoat pocket when I collected my mattress.

The moment I emptied the paint pot I realised my folly, the paint

smeared on my pyjamas would have made the obstruction infinitely more

watertight! By this time, only one survivor had floated past in the

remains of the ships launch, up-ended, the stern being deep in the

water and the bows well out of the water acting as a sail so that it

quickly drifted past and went out of sight. The northerly breeze was

light and there were no waves at all thanks to the oil on the surface -

this made me quite sick even though I had only swallowed a few drops,

but it did act as protection against the cold. Then

two young motor mechanics swam to us and were hauled onboard. I kept a

sharp look out as all three of my companions were very exhausted and

sure enough was rewarded by the sight of a destroyer passing

miraculously close at very slow speed. My shout of "Ship Ahoy!" was

quickly joined by my three companions and HMS Venomous,

beautifully handled, picked us up in masterly fashion. I noted here the

difference between a survivor and a rescuer handling a heaving line, at

my end I took a turn on a bow cleat at the other end the seaman was

forced to let go. In spite of this we were all able to step on board to

safety.

"Could we reach Casablanca?"

I

went straight to the captain's cabin, shed my oily clothes and after a

good wash left them to soak and visited the bridge in Falcon-Steward's

second best battle dress! I heard the lookout shouting, "Dark object

ahead!" It did

not take long for Commander Falcon-Steward to decide the object was the

U-Boat as it was trying to escape. With two boilers banked for economy

the response to ordering "Full Speed" was painfully slow but in due

course we started to catch up and then suddenly the U-Boat dived and,

as we passed over him, a full pattern of depth charges went down.

After turning, Venomous

was

unable to regain contact but fired a second pattern, which evidently

was sufficient to discourage the U-Boat from further adventures. Three

years later the Captain of the U-boat's report was discovered in the

German Admiralty archives,

dated 11 and 12 November 1942, with his claim to have sunk two cruisers

and two destroyers. In both cases it was wishful thinking as Marne was towed to Gibraltar and refitted to fight another day.

When dawn came Venomous

was busy picking up survivors, some still clinging to bits of timber,

some dead, others lying on small planks, a very few on Carley floats of

which the most heartwarming was the Sick Berth staff led by young

Surgeon Lieutenant Hetherington, keeping stroke with their paddles and

singing the "Volga Boat Song" together with their wounded casualties. In spite of being immobilised Marne

acted as a point of reference for the search as the wind was slight and

she would not have shifted much more than the scattered survivors. When

full daylight came it was clear that sharks had arrived and it became

necessary for marksmen to keep them at bay in case they plucked up

courage to take a bite at any of the men in the water who were too weak

to drive them off.

By noon it was decided that the search must be abandoned as fuel was getting desperately low and I suggested that since Marne could not use her ample supply of oil as she had no propellors we could try and get some from her. Cdr Falcon-Steward agreed and

signalled, asking Marne if she

could pump oil to us, we would come alongside. This was agreed and

carried out. My own idea was to obtain oil by taking Marne in tow as I had done on exercises in China at speeds of up to 24 knots, earning a welcome signal from HMS Cumberland,

"Manoeuvre Well Executed". But, unfortunately, the pumping

arrangements were too slow and the slight swell caused unacceptable

heavy bumping so we gave up the attempt and I suggested another

plan. I told Falcon-Steward that at about 10 pm the previous

night I had heard that Casablanca had surrendered to the US Navy so if

we could reach Casablanca about 130 miles to the east we would be home

and dry. Falcon-Steward then sent for the Chief and put the question

straight, "Could we reach Casablanca 130 miles away?" The

engineer officer demurred a bit then gave his verdict, "Yes we

could cover that distance on condition that we did not exceed 8

knots". So, we waved goodbye to my recent shipmates (amongst whom

I was glad to see both the Captain and Commander of Hecla)

and headed east for Casablanca. It was an anxious journey, 8 knots is a

loitering speed asking for trouble, especially if our U-boat had

withdrawn in search of fresh prey to the East, but mercifully next

morning we arrived safely.

"Who are you and what do you want?"

We

entered harbour and found the quays littered with the disgusting

results of Vichy handiwork. Hardly a berth was free of the forest of

masts and funnels of sunken ships. One was occupied by a US destroyer

with a hole in her side the size of a house another, to my immense

relief, by USS Augusta on

which I had established tremendous friends in Iceland earlier in the

year. By megaphone they asked us, "Who are you and what do you

want?". The reply was simple, "This is HMS Venomous and we have 500 survivors from HMS Hecla

who need everything from washing to clothing and a hot meal". The

response was terrific, "Lie off for ten minutes, then come alongside,

we will have a brow [US Navy usage for gangway] aft for ratings and one amidships for officers, and

there will be guides". So we really were made more than welcome

and treated royally. At the bathroom entrances sailors were stationed

with mountains of necessities: Toothpaste, tooth brushes towels, soap.

After a good wash at the exit more sailors handed out vests and pants,

khaki shirts and trousers, socks and shoes; officers even received

black ties and forage caps.

Then we were guided to mess rooms and served a very substantial

breakfast - it was noon by this time - with plenty of hot tea or coffee. Meantime, some of our

wounded were looked after in the sick bay and my cut feet were treated.

The surgeon wanted to give me a shot of anti-Tetanus even when I said I

had been inoculated two months earlier; he would not believe me but

luckily our young Surgeon Lieutenant, Stephen Hetherington, was in the queue not far behind me

and shouted I can vouch for that. Augusta’s

surgeon looked up and said, "And who the hell are you?". Not

unreasonably since we were all in our birthday suits. Anyway, he was

pacified and I was saved from an unnecessary inoculation.

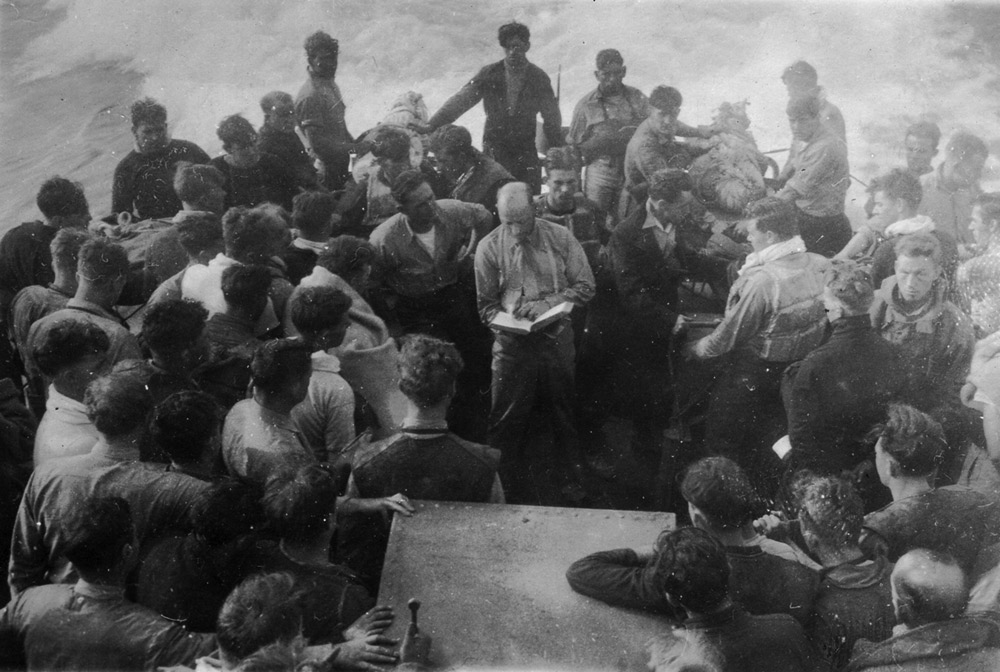

After all the survivors had been fed we returned to Venomous and shifted berth to refuel from a flat-top, the makeshift aircraft carrier of those days. This was because I had pleaded that neither officers or men had slept for 48 hours and we must have a night's rest before sailing. This was particularly important as a light rain had started and Venomous could only offer cover for a small proportion of my crew. We sailed at 3 am, however, after re-embarking two seriously wounded and two who had died in the Augusta during the night. At 10 am, having made good progress on our way to Gibraltar, the ship slowed down and at the Captain's request I read the funeral service for our two shipmates and reminded the congregation that I was also reading the service for all the other brave men, several hundred of them, who had been lost in the last few days. By evening we were inside the breakwater at Gibraltar and then started a weary round of orders and counter orders and confusion.

"I read the

funeral service for our two shipmates"

Cyril Hely gave the names of four men buried at sea from the stern of Venomous on the back of this photograph:

"Thomas

Luxton, George Taylor, Charles Odey and Alfred Dutton were buried at

sea at latitude 34 degree 30 minutes North and longitude 7 degrees 30

minutes west."

Petty Officer George William Doyle Minor, 37, who died on 12 November is thought to have been buried with them

Four men who died later were buried at sea after arrival at Gibraltar on 14 November.

Photographed by Cyril Hely

Gibraltar

We lodged in the battleship Duke of York

but it was not a comfortable ship to sleep in because of the irregular

explosions of counter-limpet mines. These were quite small

explosive charges thrown into the water from the end of the detached

mole at irregular intervals. These had proved lethal to limpeteers but

hardly conducive to a good nights rest for survivors!

Next day I was asked if I would volunteer to take home a sloop lying in

dry dock after being rammed by one of our gallant allies. When asked

why he had suddenly savaged one of his fellow escorts he produced the

logical answer, "Because painted on her side was the number U57".

So I said goodbye to my fellow survivors, who were shipped home in the Reina del Pacifico, and myself lodged on board HMS Vindictive, which was lying in the big dry dock. This was to lead to a major disaster as Vindictive's

captain decided this was the moment to get rid of his first lieutenant

and that I, regardless of my feelings would make a much better

executive officer. Quite apart from my lack of admiration for Captain

Ackland, there was the question of my survivors' leave. When I

had time I went to see the Maintenance Captain (McCann) and put my case

most forcefully, but to no avail. I never enjoyed a single day of my

entitlement as a survivor!

In command of HMS Vindictive

When Vindictive

was undocked she had to take in a large quantity of Engineers stores

and I personally supervised this up to 10 pm then got the ship ready

for sea and reported the fact to Captain H.G.D. Ackland RN shortly afterwards. We

made a peaceful passage to Mirs el Kebir but from then on the weather

deteriorated steadily. The next few nights Captain Ackland chose to

spend on the bridge, refusing my offer to relieve him. But on the third

night I was called with the information that Captain Ackland had

collapsed on the bridge and remained unconscious, so I went up there

for the rest of the night and in the morning received the young Surgeon

Lieutenant's report. He was quite rightly disturbed and I was glad to

be able to help him by drafting a signal to Admiral Syfret who had

entered harbour. "From Lt Cdr H.C. Alexander HMS Vindictive.

Regret to report that Captain H.G.D. Ackland has collapsed on the

bridge. Surgeon Lieutenant has requested a second opinion." This was

possibly the most important signal I would ever make but time was also

important so I did not delay its dispatch. Soon afterwards the Admiral's

Surgeon Commander came across by tug (as the weather had deteriorated

further). I handed him straight over to my surgeon and they proceeded

to the Captain's cabin. Nor did I speak again to the Fleet Surgeon but

as the weather was moderating I requested the Flag Lieutenant

should enquire when it would be convenient for me to call upon the

Admiral. I had no decent uniform and was kept lying off for quite a

time and the officer of the watch apologised for my being delayed

because he was expecting the Captain of HMS Vindictive. He was amazingly disconcerted by my reply, "I am the Captain of HMS Vindictive".

Captain Howson, Chief of Staff, had no difficulty in sorting out the

situation. He had been a splendid Divisional leader in the 8th flotilla

with me in China only a few years earlier. The necessary signal was

made to Admiralty recognising and approving my assumption of command.

It was not till a month later after Darlan's murder that their

Lordships suddenly realised what an important position I held with

regard to our relations with the French Admiral; so thinking it would

be helpful they sent out a Rear Admiral to take my place. After I had

turned over to him and he had accepted the confidential books he made a

signal which, on the face of it, seemed to me satisfactory.

"To

A M C X F (The Naval side of Eisenhower’s staff in Algiers) Intend to

discharge Cdr Alexander to Gibraltar for onward routing to UK."

The reply may have been flattering to my ego but most frustrating to my

hopes of survivor's leave. "On no account is Cdr Alexander to be

discharged to UK as he is required for further service in the

Mediterranean." So already Admiral Bertram Ramsey, or his staff,

considered the war in the Mediterranean could not be actively and

successfully prosecuted without my presence.

I could gladly have forgone the compliment but accepted the numerous

and varied appointments which came my way under Flag Officer Sicily and

later in western Europe. A year later I was invalided home at the time of our assault in

Normandy and was offered the first vacancy in the ranks of Beach

Parties. This did not materialise until the port of Antwerp was

seized and I worked there until April 1945 when I was transferred to

the staff of Admiral Bailey Gorman and took a convoy of 18 road

vehicles to Kiel, arriving on the 8th May.

The next chapter of this saga was told to me by the young (Hostilities Only) Gunnery officer of HMS Vindictive, a few days after I had assumed command of the ship when Captain Ackland had been invalided home.

The Gunnery Officer's Account

I

was on the bridge between ten and eleven pm because we knew we were

likely to meet a U-Boat and it was no surprise when a look-out from the

starboard side called out, "Dark object in sight silhouetted against

the moonlight". I could clearly see the conning tower and brought

guns and searchlights to bear on the target. The captain refused to

accept this was a submarine, saying, "Clearly, it is HMS Venomous".

Both the Chief Yeoman and I pleaded in vain that it was clearly a

submarine and I even added I could see the bow wave foaming all the way

from the stem to the conning tower. We simply must take defensive

action!

Very soon after this two torpedoes passed ahead of us and a heavy explosion was heard quickly followed by Hecla reporting she was hit and the engine room was out of action.

Submission to the Admiralty

Their Lordships might like to have this brief record and consider the following points:-

I When the exact location of a U-Boat was

plotted and a meeting likely at 11 pm, would it not have been prudent

to make a big alteration of course, say 60 degrees to port, till

daylight next morning, not withstanding Venomous’s shortage of fuel, which could have been supplied to her at high speed while towing before dark by Vindictive.

II In view of Hecla's maximum speed being 15 knots would it not have been better to make her guide the fleet at her best speed, with Vindictive

left with ample speed for station keeping. This was a vital

consideration in view of the probable higher speed of the U-Boat and,

together with a suitable evasive manoeuvre, might have left the U-Boat

tailing behind unable to catch up.

III Once a small and ineffective alteration of

course of 6 degrees had been adopted would it not have been wise to

order a maximum protection zigzag, say from 9 or even 10 pm. In

addition to the increased chance of torpedoes missing, the large

alterations of course would have removed the U-Boats sheltered line of

approach in the destroyers wake so that she automatically came within

the destroyers sonar effective arc.

HMS Hecla Specifications

Type: Destroyer Tender

Tonnage: 10,850 tons

Completed: 1940, John Brown & Co., Clydebank

Date of attack: November 12, 1942

Postscript

The

U-Boat that sunk Hecla was U 515 under the command of Werner Henke.

There is information on the net regarding both him and the submarine.

*******

In

January 1946 A/Cdr H.C.R. Alexander RN was appointed Kings

Harbourmaster at Plymouth and remained in that post until his

retirement from the Royal Navy in 1949 at the age of 45. A new phase in

his long life began. He separated from his wife and moved into a lovely

small house, The Dell, near the churchyard in Aldenham, an attractive village in Hertfordshire between Radlett and Watford. He was

employed by the newly established Civil Defence Corps (CDC) to prepare

the country to cope with the aftermath of a nuclear attack, a very real

prospect during the Cold War.

In

1954 he moved to Beirut to set up civil service infrastructure there

which was fully operational before the earthquake struck near Sidon in

1956 in which six thousand building were destroyed and 136 lives

lost. The rescue facilities he had established helped the

thousands who had been injured or had lost their homes or businesses.

In recognition of his achievements the government of the Lebanon

awarded him the Order of the Cedar, roughly equivalent to an OBE or a

British knighthood.

In 1958 he moved with his second wife, Mary Murdoch, to Florence, where he had spent the first eleven years of his life. They returned to London in 1962 and he worked for Barbara Reynolds at Cambridge University, to help put together the University’s new two-volume English-Italian, Italian English dictionary. Unusually, since he was equally fluent in both English and Italian he translated the military and nautical terms into both languages. Commander Alexander died in London in 1996 aged 92.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the assistance

of his son, Colin Alexander, in Ottawa, Canada, for supplying details

of his father's life after retirement from the Royal Navy and Hugh

McLintock for editing and transcribing his memoir but the details of his naval career are mainly based on his entry in the

unithistory.com web site.

Officers serving on HMS Hecla

on the 11 November 1942

| Survivors Commander G.V.B. Faulkner RN Commander J.R. D'Oyly RN Lieut. Com. H.C.R. Alexander RN Captain S.H.T. Arliss RN Captain James A. McCoy RN (not confirmed) Lieutenant John Steavenson RNVR Lieutenant Geoffrey N. Spring RNR Lieutenant Patrick J.G. Bernard RN Lieutenant Roger L. Clode RN Lieutenant David R.O. Jones RNVR Lieutenant H.H. McWilliams SANF Sub Lieutenant Graeme S. Knight RNVR Acting Sub Lieutenant Bernard Spencer RNVR Commander (E) Oswald J. Gerard RN Lieutenant Commander (E) Hugh W. Findlay RN Lieutenant (E) Rupert J. Doble RN Warrant Engineer Reginald L. Kirby RN Warrant Engineer James G. Farrow RN Francis W. Barton, Gunner (T) RN Acting Gunner Ledgerwood G. Porter RN Warrant Shipwright William F.M.A. Eddy RN Warrant Ordnance Officer Lawrence H.Farr RN Surgeon Lieut. Com. Cecil de W Kitcat RNVR Surgeon Lieut. Stephen L. Hetherington RNVR Surgeon Lieut (D) Kelvin Rees LDS RNVR Surgeon Lieut (D) Angus McPherson LDS RNVR Schoolmaster S.G. Clark Chaplain Rev Emlyn Williams RNVR |

Killed Paymaster Captain (S) Frank Leonard Monk RNR (1892-1942) Paymaster Lieutenant (S) Ernest Trevor Hackett RNVR (1914 -42) Lieutenant Guy Henry Garrett-Cox RNVR (1911-42) Lieutenant (E) Geoffrey Sims Brettell RN (1911-42) Commissioned Gunner (T) William Emmanuel Hayward RN (1898-42) Sub Lieutenant Stanley Charles Richardson RNVR Paymaster Sub Lieutenant John McKenzie Stewart Hotchkiss RNVR (1919-42) Warrant Writer, Robert Hutchison RN (1900-1942) Warrant Ordnance Officer Laurence Henry Farr RN Warrant Supply Officer Herbert Douglas Honey RN (1907-42) Mr H. Edmunds, Warrant Electrician, RN Mr W.E. Hayward, Commissioned Gunner (T), RN Mr S.C. Norcott, Temporary Boatswain, RN Mr R.J.A. Saunders, Acting Warrant Cook, RN |

Read Lt A.d'E.T. Sangster RN's "View from the Bridge" of HMS Venomous