Greg Clark joined HMS Hecla on Boxing Day 1940 as the "Schoolie" while she was being fitted out in John Brown's shipyard on the Clyde. Sixty years later on Boxing Day 2000 he was recorded by his son Nick talking about his wartime service on destroyers and the destroyer depot ship, HMS Hecla. He survived her sinking and after the war became the first Curator of the Royal Navy Museum at Portsmouth, the museum entrusted with the care and upkeep of Nelson's flagship, HMS Victory, and was 95 when he died on the 20 August 2011. Nick transferred his VCR recording onto a DVD and sent it to me with scans of some of his father's photographs. This together with notes of a conversation I had with Greg two years before he died forms the basis of this brief account of his long life.

Sidney

Gregory Clark was born at Oldham in Lancashire on the 12 June 1916, the son of Sidney Wheelhouse Clark (1884-1929), and

was only twelve when his father died. A close family friend, Uncle

Alfred (Alfred George Kelty), became something of a father figure, offering guidance and advice when needed. Uncle Alfred was an

engineering apprentice in the

Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS) in World War I and after the war received a government grant to study engineering at Jesus

College, Oxford. Greg went to Manchester

University to take a science degree but was more interested in writing

and rather

neglected his studies. He wrote short stories, cultivated contacts with

the local press, helped them out at trade shows and worked part time

for the Polish Telegraph Agency (Polpress) as their "foreign

correspondent" paid per article.

Sidney

Gregory Clark was born at Oldham in Lancashire on the 12 June 1916, the son of Sidney Wheelhouse Clark (1884-1929), and

was only twelve when his father died. A close family friend, Uncle

Alfred (Alfred George Kelty), became something of a father figure, offering guidance and advice when needed. Uncle Alfred was an

engineering apprentice in the

Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS) in World War I and after the war received a government grant to study engineering at Jesus

College, Oxford. Greg went to Manchester

University to take a science degree but was more interested in writing

and rather

neglected his studies. He wrote short stories, cultivated contacts with

the local press, helped them out at trade shows and worked part time

for the Polish Telegraph Agency (Polpress) as their "foreign

correspondent" paid per article.

By the time he graduated it was all too clear that war was coming and his uncle encouraged him to volunteer for the Royal Navy before conscription was introduced. After initial training in gunnery and torpedoe control at Plymouth he was halfway through an abridged navigation course at Portsmouth when war was declared on the 3 September 1939. Greg Clark was appointed as a Schoolmaster, popularly known as a "Schoolie", with Warrant Officer rank (and a single blue stripe on his sleeve) in the Royal Navy Education Service. He was posted to HMS Impregnable, a boys training establishment at St Budeaux in Plymouth and later to HMS Pembroke, the shore base at Chatham on the Medway for assignment to destroyers. He was moved between destroyers within the flotilla and as a junior officer had to sleep in a hammock when no bunk was available. The doctors posted to destroyers took priority when it came to accommodation. His role was to prepare the young conscripts for their return to civilian life after the war and to assist with cipher work, coding and decoding messages received and sent by the Wireless Telegraphy Operators. The Surgeon Lieutentants also helped with cipher work.

The destroyers in his flotilla mainly escorted Atlantic convoys to St

Johns, Newfoundland, via Iceland but he made one trip to Dunkirk, bringing French troops to Plymouth. He was on eleven convoys between

January and November 1940. The fast convoys, usually tankers, moved at

8 knots but slow convoys of smaller merchant vessels only managed 5

knots with the speed set by the slowest ship. He described the horrow

when a merchant ship was hit and the convoy continued, unable to stop

and rescue survivors. When they took the southern

route the convoy dispersed on reaching Freetown in west Africa as the

U-boats did not

have the range to penetrate that far south until later in the war.

HMS Hecla on the Clyde after being fitted out

Courtesy of Nick Clark

Destroyers did not need a full time Schoolie and his posting to HMS Hecla,

a destroyer depot ship

made good sense. Depot ships were based in remote parts of the world

where there was no dockyard to undertake essential repairs and

destroyers could moor alongside for repairs as minor as clearing

blocked "heads", as routine as a boiler clean or a major repair.

Medical, recreational and educational facilities were also available to

their crews. He joined HMS Hecla

at John Brown's shipyard on the Clyde on Boxing Day 1940 while it was

being fitted out, the first of three identical depot ships in the Hecla Class to be completed.

On New Year's Eve he was told by Captain C.G.B. Coltart RN, "Schoolie,

you are the youngest officer aboard and, therefore, will ring out the

old year with eight bells and ring in the new with eight bells."

HMS Hecla

became the destroyer depot ship at Havelfjord in Iceland, repairing the

destroyers escorting the Atlantic convoys to northern Canada. HMS Venomous was always breaking down and was a frequent visitor. French

and Polish destroyers also berthed alongside for repair. Iceland was

cold in winter (care had to be taken clearing the deck of snow not to

sweep it onto destroyers lying alongside) but very hot in Summer. Greg

recalled climbing Mount Hecla on a summer day and seeing local people

bathing naked in the sunshine. There was very little to do in Iceland

and life became boring. He remembered the capture of a German U-boat, U-570, which was renamed HMS Graph and became the only sub to fight on both sides. Churchill visited HMS Hecla

and Greg remembered a show put on by ENSA which "was really awful". Finally,

he was allowed to accept the invitation of a destroyer captain to join

his ship and escort a convoy to Canada, spent ten weeks in the USA and

even learned to drive.

American forces relieved the British in garrisoning Iceland, USS Vulcan joined Hecla as a depot ship at Havelfjord and early in 1942 after Pearl Harbour and America's entrance into the war Hecla

returned to the Clyde for a refit before being redeployed to tropical

waters. Two more medical officers joined their Sick Bay team. Hecla's

destination was kept secret from the officers and crew but Greg Clarke,

the Schoolie who helped decode the secret instructions taken down by

the Wireless Telegraphers knew they were to be based in the Maldive

Islands, a tropical paradise in the Indian Ocean with a maximum height

above sea level of only twenty feet. After the war Greg Clarke received

a campaign medal for service in the far east but they never reached

their secret

destination. As they rounded Cape Agulhas at the southern tip of South

Africa on the 15 May they struck a mine which blew a hole the size of

four buses in the hull of HMS Hecla,

the torpedoes and machinery stowed in the hull were lost. Twenty one

men were killed but they made it into the naval dockyard at Simon's

Town under their own power.

HMS Hecla was under repair from May to October 1942 and although seaworthy she was still in need of major

structural repairs when they headed north. On reaching

Freetown they received orders to proceed to Algiers for the landings in

North Africa, Operation Torch.

Shortly after 2300 hrs on the 11 November 1942 they were hit by the

first of five torpedoes fired by U-515. Greg Clark was on the Bridge

when the first torpedo struck. Bizarrely, he went to his splendid

cabin, one deck down at the stern to retrieve a pile of South African

pound notes and while returning to the Bridge looked back and saw a

torpedo strike the ship's magazine beneath his cabin. Their two

destroyer escorts, HMS Venomous and HMS Marne,

fired star shells to illuminate the night sky as they pursued the

attacking U-boat - or boats. The order to "abandon ship" was passed by

word of mouth. Greg Clark was in charge of a cutter but as it was

lowered the falls broke and it fell into the sea. Greg had been advised

by a fellow officer who had been torpedoed before to get away from the

suction of the sinking ship as

quickly as possible. He was a strong swimmer, got

clear of the ship and at dawn swam to a crowded Carley float, grabbed a

rope loop on

the outside of its tubular frame and hooked his feet onto the

grating hung inside by chains. Men fought for places, cried out to

their mothers or wives, struggled to survive, despaired, gave up and

drifted off. Greg lost consciousness from a blow on the head and had no

memory of being picked up in the afternoon by HMS Venomous

and taken to Casablanca captured by the Americans that morning. He was

given a battledress to wear, fed and slept aboard a USN aircraft

carrier

before Venomous left for Gibraltar the next day. Most of the

survivors returned to Greenock on the liner, Reina del Pacifico. On landing and queuing to receive back pay he was shocked to be handed it by the grieving widow of a fellow officer on Hecla; his own Mother had been told he was "missing, believed killed."

Life after Hecla

After survivors

leave Greg Clark was posted on the 4 January 1943 to HMS Gosling,

a new entry training establishment at Risley near Warrington,

Lancashire. He was back on destroyers escorting Atlantic convoys

from Liverpool. Bored with this

familiar routine he applied for an overseas posting hoping to be

sent to Bermuda and was

disappointed when on the 5 December 1944 he was sent to join the staff of HMS St George on

the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea. This former holiday camp had been

turned into a shore base for training the boy sailors from HMS Ganges at

Shotley in Suffolk opposite Harwich which had been taken over for

training of hostilities only ratings. While stationed on the Isle of

Man he met his future wife, Alice Long.

On New Year's Day 1946 when the young entrants to the Royal Navy returned to their former base at HMS Ganges he joined them at Shotley and the following month was promoted to Instructor Lieutenant. Greg Clark stayed on

in the Royal Navy and on the 5 January 1947 he was posted to HMS Mull of Galloway, SORF Clyde, a modern repair ship with a similar function to HMS Hecla. In

1967 he was awarded the MBE in the New Years Honours List and in 1972 he retired as Cdr Sidney Gregory Clark RN. His wartime service in the Royal Navy in the Education Service of the Royal Navy can be seen on the unithistories.com web site.

Cdr

Greg

Clark RN (Ret) retired from the Royal Navy Instructor Branch in 1972

and transferred to the civil service when he joined the staff of

the Victory Museum alongside Nelson's flagship in the Portsmouth

dockyard. Mrs Lily McCarthy,

an American millionairess, bequeathed the Lily Lambert McCarthy

Collection of Nelsonia to the nation and Greg Clark was appointed its

Curator and recruited men from the “Regulating Branch”

(naval police) as wardens. It was merged

with the Victory Museum to form the Royal Navy Museum with Captain Jimmy Pack RN

as its first Director. The Japanese Navy

was modeled on the Royal Navy and in 1976 Greg Clark

spent some weeks in Japan curating a cultural exhibition on "Britain

and the Sea" for the British Overseas Trade Board and raising funds

from wealthy Japanese

businessmen, admirers of the Royal Navy and its traditions. When he

retired in

1983 his research assistant, Colin White,

a history graduate from Southampton

succeeded him as Curator, gained an international reputation as

"Nelson's representative on earth" during the bicentenary celebrations

of the Battle of Trafalgar in 2005 and the following year was appointed Director of the Royal Navy Museum.

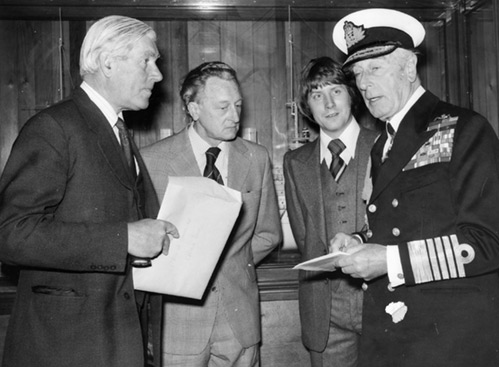

Left: Greg Clarke with some young visitors to HMS Vanguard (Copyright Mickey Mouse Weekly)

Right: Captain Jimmy Pack, Greg Clarke, Colin White and Earl Mountbatten at the Victory Museum (Copyright RN Museum)

Greg Clark had several books published including Britain's Naval Heritage (Royal Navy Museum, 1981) and Doc: One Hundred Year History of the Sick Berth Branch (Royal Navy Museum, 1984).

Perhaps significantly, he would have had a close working relationship

with the Surgeon Lieutenants on HMS Hecla and the destroyers on which

he served since schoolmasters and doctors were both required to help

with cipher work.

The book launch for A Hard Fought Ship

was held at the Royal Navy Museum in April 2010 but at the time I did

not know that the life of its Curator had been saved by HMS Venomous

and nor did I know that he was still alive, in good health and living

in Portsmouth. If I had known he would certainly have been invited to

the launch which was attended by veterans of both HMS Hecla and HMS Venomous.

Greg Clark continued to live in Portsmouth until his death at the age

of 95 on the 20 August 2011. His ashes were scattered on the sea off

the Isle of Man, where he went for R & R after the sinking of HMS Hecla and met his wife, Alice Long.