George

Arthur Gregson (1891 - 1963) was born in Preston and graduated from

Liverpool University with a B Eng in 1914. He was rejected by his

stepmother when his father remarried after his mother's death and his record of service in the Great War gave

a home address in Colwyn Bay, North Wales, and a Mrs Forrest as the

person to be notified in the event of his death. He was described as a "non practising" mechanical and civil engineer specialising in automobile engineering with

"motor racing experience". He became a junior officer in the 98th Field Company of The

Royal Engineers, part of the 21st Division established in September

1914, which embarked for France on the 10 September

1915. You can read more about his service career in France with the Royal Engineers and learning to fly with the Royal Air Force in 1918. George

Gregson was wounded three times during his wartime service in France.

The loss of the little finger on his left hand was not serious but it

prevented him from playing the violin. He also had a bullet wound in

his right elbow and a shrapnel wound in his back, on the right.

Estranged from his own family Captain George Gregson decided to start a new life in France. He

settled in Amiens and started a business hiring chauffeur driven

cars to church groups visiting the graves of men who died in the war.

He met his French wife, Gisèle Dessaint, about 1921 and they

had two sons, Maurice (1925) and Dennis (1927). The family moved from

Amiens to Boulogne before finally settling at Calais where George

Gregson became the agent for the Automobile Association. His business

prospered. As well as the family home in Calais they rented a house in the

country at Escalles and George owned a Rolls Royce which he hired out

to

tourists. Their two sons were born in France but sent to England to

receive a British education at the Kings School in Canterbury.

The Gregsons were wealthy members of the British community and had a good life. All of this was threatened when Germany's invasion of Poland led to war. For eight months little changed but on the 10 May German forces invaded the Netherlands, bypassed the vaunted Maginot Line and swept on into France encircling and then dividing the British Expeditionary Force. British subjects living in Belgium and northern France were trapped, cut off from the south with the only escape being by sea. If they failed to get away they would be interned as enemy aliens - just as Germans were in England.

Left: George

Gregson with his family in the garden of their rented

cottage in Escalles in the Summer of 1939. Maurice and Dennis returned

to their boarding school in England and did not see their father again

until 1944.

Left: George

Gregson with his family in the garden of their rented

cottage in Escalles in the Summer of 1939. Maurice and Dennis returned

to their boarding school in England and did not see their father again

until 1944.

In May 1940 George Gregson was a

prosperous middle aged businessman of 49 weighing nearly 18 stone but

he was a veteran of the Great War and determined to fight for his

country in this new war which threatened his family. On Wednesday the

15 May, five

days after the Germans launched their blitzkrieg and less than a week

before Calais fell he left his wife at

their home in Calais and drove to Amiens in his own car to join the

British Army.

His wife, on her own and unable to drive but with lots of good friends

in Calais, showed a

great deal of determination and initiative in getting to England aboard

HMS Venomous from Boulogne on

the 22 May 1940. The morning after she was reunited with her sons at

Folkestone she wrote to her husband. He never

received her letter and it would be many months before he knew she

reached England safely.

Her letter, written

in a rush, is both very

detailed and rather confusing, mentioning the names of their friends in

Calais

without needing to explain who they are and what happened to them. She

left

Calais on Monday 20 May for Dieppe in her husband's Rolls Royce with

the Deguines family

and a mechanic at the Peugeot agency as the driver. They seem to have

spent Monday night at their cottage in Escalles near coast eight miles

west of Calais. Had she stayed in Calais until the Tuesday she might

have got to

England on Venomous with the

Ratcliffe and West families a day earlier. As it was the roads were

clogged with traffic trying to escape to the west unaware that German

forces had already reached the coast at Abbeville cutting off the route

to Dieppe and were encircling

Boulogne. They were straffed by German aircraft at Camiers and were

advised to turn back to Calais. They had to abandon the car at

Pont-de-Briques south of Boulogne where the

police were barricading the road and walk the 7 kms back to the city

where they spent the night in the home of a friendly school inspector.

The Gare Maritime was crowded with Belgium refugees who seemed to feel

they had priority but she spoke to an English army sergeant, showed

him her husband's passport and was given a boarding pass but it is not

clear from her letter whether the Deguines children were able to

accompany her.

"This letter

written by my grandmother to her husband, George Arthur Gregson, on

arrival at Folkestone never reached my

grandfather who spent several months without any news from his wife.

The last paragraph was added by Denis Gregson, my father, then aged 13

and schooled in England." Anne Gregson

Darling,

I hope that this letter will reach you and set you mind at rest. What a

time I have had, my dear! What terrible things I have seen. Today is

the first time since Monday that I have felt a little better.

I arrived yesterday on a destroyer, HMS Venomous. Mr Reight [Wright?] has been wonderful, and since then they have become far more than mere acquaintances. But I'll try to recall for you these hours that I shall never forget.

The day after you left, Calais was bombed again. On Friday everybody panicked. Everybody was leaving, the Dubreucq, Mrs Sharp and her daughter, and others. I did not know what to do as the "Boches" were getting closer. On Saturday, at the Consulate, I was advised to take the merchant ship that was leaving the next day. I went to see Mr Oldham but he wasn't in. I asked the Lhadens for advice but they didn't know what to do either. I was getting quite flustered. I went to see the Deguines, they wanted to leave but did not know how as the trains weren't running and all those Belgians, thousands of them, were passing by with their bundles or in a car. Mrs Pezron, who had spent Wednesday and Thursday nights in Calais, had intended to go home like the Deguines and were happy to have escaped the bombings. But the bus is not running so we shall take the "Starn." Mrs P. did not arrive at Sangatte. We are going to walk.

I forgot to tell you that at around half past five I had an idea: the Rolls being at Peugeot's and Mr Deguines being able to drive, we could all go to Dieppe. I thought the car was unlocked. After giving the order to have it ready and after giving a big tip for gasoline as I had no coupons. But it was locked and we couldn't open it. So we waited until Sunday to try and find a solution.

I continue. On

arrival at Sangatte we went to see Mr Tait. He was also planning to

send his his wife and Verbeck to Dieppe. That night was

terrible. At Blériot, people panicked and fled; those who went to the

dunes were strafed by the "boches" . The English DCA [défense contre

les aéronefs, anti-aircraft defence] had just arrived and

did a good job. The next day, Sunday, we returned to the Rolls. But Mr

Deguines is nervous about driving such a big car. But since we can't

find a driver in Calais, he agreed to drive. We found a locksmith who

should come on

Monday. So everything was for the best. But on Monday, when Mr Deguines

took the wheel he had problems driving the car.

In the meantime, I saw John. He also advised me to leave. At seven o'clock as we were about to give up and walk, we are told that a Peugeot mechanic wants to leave with his wife. We go and see him and again we feel hopeful. We agree to pay for his food and accommodation and he would drive us to Dieppe, then go to Alençon with the Deguines, there he would leave his wife and bring the car back to Dieppe with Mr Deguines; who would then catch the train to Calais. Mrs Pezron would remain at Escalles with Narvik and Mr Oldham could come in the evening if necessary. Mr Clausen and another also asked me if they could sleep at Escalles. In short, everything was too good to be true. So we set out at 7am on Tuesday. Mr Deguines found 80 litres fuel. I take with me as much as I can, silverware, some special children's' clothes, lingerie, etc. but I should have taken nothing. We leave without difficulty behind a line of hundreds of cars.

Arrived at Wimereux,

as we were doing only 10 km, I see Sexton, poor

guy. I tell him that I am going to Dieppe and with a sad expression,

which should have struck me, he said: "If you can." I thought he meant

that the road was congested. I asked him for news of Albert, he said:

"No

doubt in Belgium." We arrived at Boulogne. There, what a mess! Then, a

few kilometres further, the engine overheats, the fan belt had come

off.

Fortunately the driver was a good mechanic and you had spare parts. We

set off again and arrive at Camiers. Here we see cars coming

back. We ask why. Some

advise us to continue, others tell us that we cannot go on. We are told

to stop and have to park by the side of the road at Camiers. I was

hoping to see you and I waited by the roadside

There, I asked an

interpreter what was going on. He looked surprised at first, but I told

him who I was and everything else. Amazingly, he was the nephew of the Watneys from Calais

and he also knew Mr Oldham who told me the Watneys had already left. So he took me to a

less congested route, and advised me to leave immediately for Calais.

The "Krauts" were on the way, the bridges were cut.

So we leave and had

only gone a little further when these cowards began to machine gun us.

At this point, my lucky star intervened, we jump down from the car, on

the right a small

dead end, and we lie against the wall on the right, flat on the ground,

on top of each other.

The Deguines children stayed near me. There were chairs. The youngest,

I

will never forget, handed me a nearby chair while the older boy

screamed to have one too. The chairs would not protect us,

but the gesture was beautiful. The shells struck but fortunately on the

left hand side of the dead end and then an incendiary bomb on a house

ahead. In short, something terrible that I cannot forget.

Somehow, after being quite terrified, several British bombers quickly arrived and chased them away. We got back into the car and arrive at the level-crossing at Pont-de-Briques. A few meters further on we are stopped. We were in the second car. The first did not want to obey the orders of the "policeman" who wanted to use it as a barricade, so he burst the tires. Seeing this, Mr Deguines still asked if he could pass, but the policeman pulled out his revolver. So we left the car there and, darling, I had to leave everything. We were 7 kms away from Boulogne. I just took the jewelery, Maurice's stamps and some of your books, which I had to leave at Boulogne.

We arrived at Boulogne in a sad state. We wanted to find a car. Of course, impossible. We head for Calais on foot. We were in Magenta Street when suddenly they are back and at this height, we saw the bombs explode on the quayside. We ask a woman: "Shelter?", She answers: "Go away." That is French brotherhood for you. Fortunately there are good as well as bad. We knocked on a door, that of a former school inspector, and what a wonderful man! After he found out who we were we were able to eat, drink, sleep, and were given everything we wanted and as much as we needed.

On Wednesday morning, I went to the consulate to try to sail with the young Deguines as the police advised me just before they closed. At first, I was told that Mr Carter had left. At the last minute, I find out that he is still there. After a long wait, I am told that I can leave, but not the children. So I go but I still try to take them with me, but a Belgian policeman stops me because of my British passport and tells me that I can't go first; so we argue. There were thousands of young Belgians who wanted to get the hell out. Seeing my passport and smiling, I am told: "Calm down, calm down, Madam! Come, women and children first. And then those future soldiers" The Belgian, policeman mollified, let me go. It was 11 am and since Monday, I'd had nothing to eat or drink. There I was with a few Belgians who looked at me rather disagreeably. One of them, seeing me so unhappy, spoke gently to me. He was a policeman from Liège, who had served in the other war, he had lost his wife and little girl of seven years and somebody had told him that his wife had been killed. He cheered me up a little. Suddenly, I have an idea. I had your passport with me (it was 2.15 pm) and there were soldiers everywhere with fixed bayonets but I went to find the English Sergeant, and showed him your passport, explaining my case and, great, you saved me. I am led to the RTO [Radio Telephone Operator] where I am given a boarding pass and two hours later I was on the Venomous with other people who had waited up to nine days in the station, under bombardment.

The sailors on the destroyer were admirable, giving food and drink to all. Two French children with their grandmother, who had been wounded, one on the ankle and the other on the hand, were being treated. During the crossing, which was amazing, one hour from Boulogne to Folkestone, Boche planes tried to bomb us, but the ship's guns and the Hurricane escort defended us and I wept with relief when landing. There I met Mr Reight [almost certainly a mis-spelling of Wright], who was really nice. I've been with Denis since this morning and I will go to Devon with Mr Davidson. Denis also goes there.

I am happier now, but I think of you and I want to hear from you very much.

Gisèle

Dear Dad,

Mummy was very pleased and glad to see me. I think we are going to

be

evacuated to Devon. I was glad to see Mummy. We could not change any

French money so we went to Barclay’s bank where a man changed 2000

Franks. You can’t change any French money here now. Mummy was surprised

to see Folkestone, for everyone was happy, not like Calais.

I hope to hear news of you soon.

With love from Denis

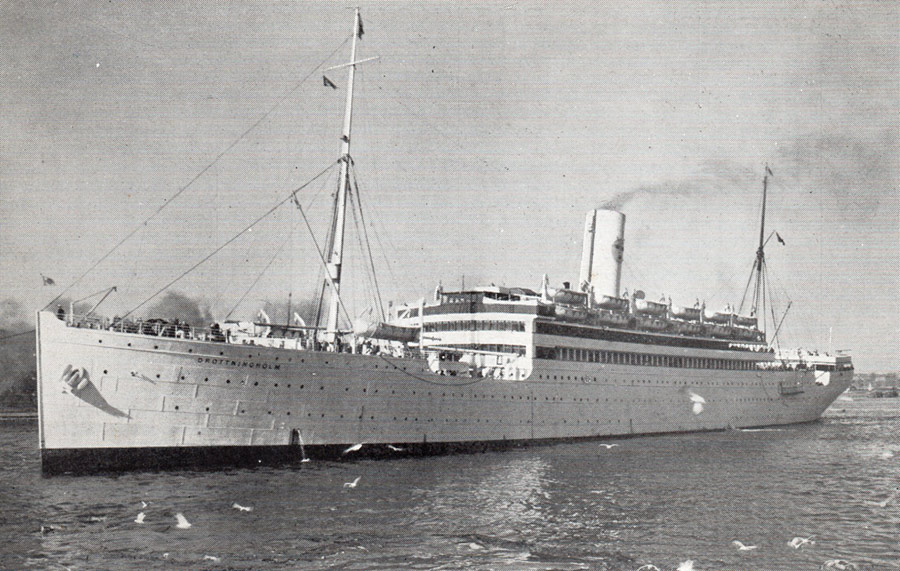

HMS Venomous leaving Boulogne with 212 refugees including Gisèle Gregson and the nuns, teachers and orphan children

Note the triple mount for'ard torpedo tubes and the two

4.7 inch Guns pointing east and the Ponte Marguet swing bridge in

background

Photographed by Lt Peter Kershaw RNVR

"Mr

Gregson had been in a distressed state of mind for some months so it

was decided to give him a change of surroundings and the advantage of a

thorough medical examination and treatment by sending him to another

hospital which is at Stalag VIIIB Lamsdorf. This was done in June."

A

further letter from Miss Thornton on the 10 February 1944 quoted from

the report of the doctor at Stalag VIIIB, Captain J.A. Mulligan RAMC:

"Mr

Gregson was admitted here on the 5.6.1943, and on the 1.7.1943 he was

transferred to a special hospital for nervous disorders. I saw him

there on the 4.11.1943. He has lost a lot of weight in the last three

years but now appears to be retaining his weight at a reduced level. He

eats well and has no bodily complaints. He has, however, delusions of a

persecutory nature, which give him great worry and keep him physically

over active. Apart from these delusions he talks quite naturally, and

takes a keen interest in his surroundings. He is very worried about his family, and is afraid that his past actions may harm his sons career."

Gisèle described him "as being almost mad" but

once he was reunited with his family he made a good recovery and not

long after the war ended they returned to their home in Calais and he

once again became the practical hard working businessman supporting the

family. His two sons assumed joint control of the business when he

retired, one running the office in Calais and the other the office in

Boulogne. The events of May 1940 had a dramatic effect on all of them

but it did not destroy the family. George Arthur Gregson was 72 when he died at Calais in 1963. His wife lived

another twenty years and was 81 when she died in 1985.

Their grand

daughter Anne Gregson has seen their stories are not forgotten

but regrets not having asked more questions about this critical period

in both their lives. Some parts of her Grandmother's letter and her Grandfather's journal are likely to always remain obscure.

Read about George Gregson's service in two world wars and his internment at Tost (Illag VIII)

Return to the Evacuation of British citizens from Calais in May 1940

The story of HMS Venomous is told by Bob Moore and Captain John Rodgaard USN (Ret) in

A Hard Fought Ship