George

Gregson was a prosperous businessman living with his French wife in

Calais when the German blitzkrieg swept through the Netherlands and

into France cutting off their escape to the south and west. He left to

join the British army while his wife escaped from Boulogne aboard HMS Venomous on the 22 May 1940.

Before describing his internment along with 1,130 other British subject

(including P.G. Wodehouse) it is necessary to start by describing his

early life and explaining how he came to live in France.

George

Gregson was a prosperous businessman living with his French wife in

Calais when the German blitzkrieg swept through the Netherlands and

into France cutting off their escape to the south and west. He left to

join the British army while his wife escaped from Boulogne aboard HMS Venomous on the 22 May 1940.

Before describing his internment along with 1,130 other British subject

(including P.G. Wodehouse) it is necessary to start by describing his

early life and explaining how he came to live in France.

George

Arthur Gregson (1891 - 1963) was born in Preston and graduated from

Liverpool University with a B Eng in 1914. He was rejected by his

stepmother when his father remarried after his mother's death and his record of service in the Great War gave

a home address in Colwyn Bay, North Wales, and a Mrs Forrest as the

person to be notified in the event of his death. He was described as a "non practising" mechanical and civil engineer specialising in automobile engineering with

"motor racing experience". He became a junior officer in the 98th Field Company of The

Royal Engineers, part of the 21st Division established in September

1914, which embarked for France on the 10 September

1915.

More

than twenty five years later while interned in France he described in

his journal an incident in June 1917 which continued to prey on his

mind. The Germans had fallen back on the Hindenburg Line and Gregson

accompanied by a Corporal Twizell of the 16th Battalion, Yorkshire

Regiment "laid out direction tapes from the front line for an attack to

be made about dawn by the Northumberland Fusiliers". They came under fire and both men were wounded, Corporal Thomas Lightfoot Twizell in the lung. The Corporal's wound healed badly and when he came under

gas attack in 1918 it eventually proved fatal and he died at home on

the 13 November 1919. Gregson thought he was in some way responsible

for Twizell's death and the incident was brought back to mind by

meeting his son while interned in March 1944.

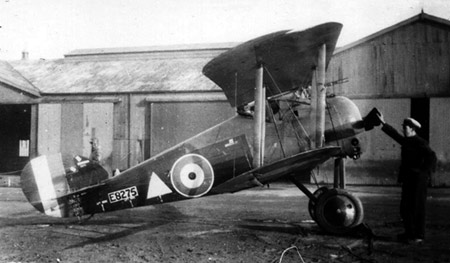

George Gregson was attached to the RAF in August 1918 after the

Royal Flying Corp (RFC) and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) were

merged to form the RAF on the 1 April 1918. He may have

welcomed the opportunity to train as a pilot but had the war lasted

longer he would probably have been posted as a non-flying engineer

officer to an operations squadron. He was "under instruction" on two

seater Avro 540s at 41 Training Depot Station (TDS) in

London Colney to the south of St Albans and at 54TDS at Fairlop north of Ilford, both part of the South East Area

Training Group (and inside London's M25 orbital motorway) and also spent some time at the RAF Armament School at Uxbridge. The

photographs were taken at 41TDS which had two flight groups and an

official establishment, laid down in autumn 1918, of 24 Avro 540 and 24

single seater Sopwith Snipes. He may have

had a minor flying accident as he was admitted to the RAF Central

Hospital from the 2 - 21 February before leaving the service on the 29

March 1919.

George

Gregson was wounded three times during his wartime service in France.

The loss of the little finger on his left hand was not serious but it

prevented him from playing the violin. He also had a bullet wound in

his right elbow and a shrapnel wound in his back, on the right.

George A Gregson in the cockpit

of a single seater Sopwith Snipe E8275 biplane he flew at 41TSD (London Colney) in late 1918

The Sopwith Snipe came into service in late 1918 a few weeks before the end of the Great War

Courtesy Anne Gregson

Captain

George Gregson was discharged on the 29 March 1919 and not having a family decided to start a new life in France. He

settled in Amiens and hired chauffeur driven

cars to church groups visiting the graves of men who died in the war.

He met his French wife, Gisèle Dessaint, about 1921 and they

had two sons, Maurice (1925) and Dennis (1927). The family moved from

Amiens to Boulogne before finally settling at Calais where George

Gregson became the agent for the Automobile Association. His business

prospered. As well as the family home in Calais they had a house in the

country at Escalles and George owned a Rolls Royce which he hired out

to

tourists. Their two sons were born in France but sent to England to

receive a British education at the Kings School in Canterbury. The

Gregsons were wealthy members of the British

community and had a good life. All of this was threatened when

Germany's invasion

of Poland led to war. For eight months little changed but on the 10 May

German forces invaded the Netherlands, bypassed the vaunted Maginot

Line and swept on into France encircling and then dividing the British

Expeditionary Force. British subjects living in Belgium and northern

France were trapped, cut off from the south with the only escape being

by sea. If they failed to get away they would be interned as enemy

aliens - just as Germans were in England.

George

Gregson's tailor made him a khaki uniform (without insignia) and he

left in his own car to join the British Army on the Somme. In 1943 he

wrote a detailed but confusing account of what happened in the month

before his return to Calais and internment.

He returned to their rented cottage at Escalles eight miles west

of Calais on the 15 June, exactly a month after he left to join the British army:

"Returned home, finally, very tired after a long and rather weary walk

of some 27 or 30 km. With my wretched ill-fitting clothes and my

uncut beard, I certainly looked very much like a tramp and my own

family would have found it difficult to recognise in me their usual

well-dressed Daddy."

George Gregson never received the letter his wife wrote on the 23 May 1940, the day after she reached Folkestone aboard HMS Venomous,

and it was several months before he knew she had reached England safely

and had been reunited with their two sons, boarders at Kings School,

Canterbury.

He

stayed at the cottage in Escalles for six weeks, spending his time

growing vegetables and cycling into Calais to visit friends and find

out who had got away. Mrs Pezron helped look after him and the German

soldiers billeted with them who dragged mattresses from the house into

the garage as beds did not seem too concerned when they found out that

he was English.

He kept a journal, written in English, which has been transcribed by Anne Gregson, the

daughter of of Denis Gregson, the younger of his two sons. The first volume of his Journal, some 20,000 words, ends with these words "These past few weeks at Escalles will probably stand out as

happy ones in the future".

He

had to register as a British subject at the Town Hall in Escalles and

on the 26 July handed himself in to be interned. After two days his

group was taken by train to Lille and interned in the Négrier

Barracks until the 26 November (see volume two

of his Journal) when they were transported via Berlin to their

permanent place of detention, the internment camp Illag VIIIH at Tost

(Toszek), forty miles north east of Katowitz (Katowice) in Upper

Silesia, now part of Poland.

Volume three of George

Gregson's Journal is a detailed and very interesting

account of his internment at Tost. It provides a daily account of his own personal

experience, describing the daily routine,

food and his fellow inmates many of whom he knew from Calais.

Volume three of George

Gregson's Journal is a detailed and very interesting

account of his internment at Tost. It provides a daily account of his own personal

experience, describing the daily routine,

food and his fellow inmates many of whom he knew from Calais.

The best

known was P.G. Wodehouse, the comic author of books about Bertie

Wooster and his butler, Jeeves, who was criticised for his Berlin broadcasts including an amusing account of the Tost internment camp. Wodehouse completed his novel Joy in the Morning, and wrote Full Moon, Spring Fever, and Uncle Dynamite while interned. BBC Four broadcast a drama "Wodehouse in Exile"

on the 25 March about this controversial period in his life which

hinted that the report clearing him from being a traitor was suppressed

to protect a double agent, Mackintosh, a man viewed with deep suspicion

by George Gregson.

The

internment camp at Tost was a former barracks used as a "lunatic asylum". When George Gregson arrived on the 29

November 1940 there were 1,130 detainees and he was placed in Room 501

on the top floor with bunk beds for 72 men.

Not all the detainees came from France, the first to arrive were from

the Netherlands and they tended to run the Camp - to the annoyance of

the French. They were, of course, all British subjects.

His

rheumatism made climbing to the fifth floor difficult and on the 18

December he was allowed to move to Room 309 on the third floor where

his friend Ernest Dutnall slept. He wrote in his Journal that:

"I

have retained my bottom bunk and on the top one there is a big man

named Burke - a real elephant of a man. He has gone through the planks

of two beds up to now, so my position is perhaps one of some danger!

However it is a warm room, good educated fellows in it and I am next to

Dutnall and have only three floors to climb instead of five."

On the 23 December he wrote:

"Yesterday

afternoon an American journalist came in to see P.G. Wodehouse, who is

in our room too. He took a photo of Wodehouse and some of us, including

me, grouped round P.G. and also asked me about our supper ration -

Germans were of course present all the time. So, perhaps,

Gisèle will one day see this photograph in the paper - I doubt she will recognise me."

This photograph and interview by Angus Thuermer published in the New York Times on December 27 1940 eventually led to the release of Wodehouse and his broadcasts from Berlin to America in July 1941 describing his internment. Their subsequent broadcast to Britain, done without his consent, nearly led to him being put on trial as a traitor after the war and he never lived in Britain again.

Gregson

was often critical of Wodehouse. On the 26 February 1941 he wrote in is

Journal "we hear that P.G. Wodehouse has - through interviews - told

the world what a splendid place it is and how well we are treated, etc

...! Well, two days ago he told Dutt that he did not mind which side

won as long as the war finished soon - and that shows his mentality as

a so-called Englishman." But on the 2 March he changed his table at

meal times and wrote "am now on the same as Wodehouse, Webb, Davies,

Rainey, [Tom] Sarginson, Dutnall, Youl, Pickard and Baryball. Much better in every way."

Tom

Sarginson

was born in Paris and brought up in France by his English father and

French Mother. He was a mechanic in the Royal Flying Corp during the

Great War and returned

to France in 1926 as the electrical engineer at Courtauld's newly

opened rayon factory in Calais, Les Files de Calais SA. Despite having an English wife, Nell, and three young daughters

he thought there was no need to "panic" and return to England. He was

interned

leaving Nell to look after their daughters on her own. The

youngest, Jeanne Gask, tells Tom's story on this web site and the story

of "Nell and the Girls" in a book to be published

in May 2015.

Wodehouse

was released from Tost with a fellow internee, Macintosh, who George

Gregson disliked and mistrusted. On the 30 March 1941 Gregson wrote:

"I

don't trust him any longer. Supposedly a professor of comparative

theology at the university of Hong Kong, picked up whilst "on holiday"

at Boulogne, he seems to have achieved popularity with the lower

elements by a liberal use of their vernacular and by being very

anti-German in his behaviour. Now, however, he appears to be turning

"Yes-man" to the Germans. I may well be mistaken of course: there are

many mystery men here and one learns to trust no one and keep ones

mouth shut. My mistrust, however, is based on the fact that he was the

principal instigator of the decision to let 1,000 odd men have 2 Red

Cross parcels each and let another 100 go empty; and that later when I

wanted to run an exchange office free for all, so that men could get in

touch with each other for exchanges of food and clothing, he adopted

the role of an unselfish purist and said that no exchanges ought to be

made but that men should give away articles they did not want. Such an

altruistic attitude coming after the previous attitude, has aroused my

suspicions."

The

Macintosh referred to is believed to be Noel Macintosh, born at

Southease in East Sussex on the 20 December 1885 and arrested at

Boulogne on the 10 July 1940. He is probably the Noel Macintosh who was

released with P.G. Wodehouse and stayed with him for a few days at the

Adlon Hotel, Berlin, and may have helped persuade him to make the

broadcasts which led to Wodehouse's self imposed exile in the United

States.

The

Commander of

Illag VIII arranged for the internees to be photographed

in groups to show how well they were being treated. The photograph

below was probably taken quite early when they still had some

respectable clothes to wear. The men in the front row have clean

handkerchiefs in their top pockets, flowers in their lapels and have

even

polished their boots.

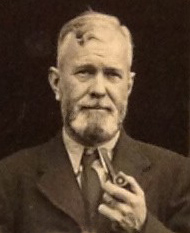

George Arthur Gregson, with pipe, is third from left in the back row in this photograph taken at the Tost Internment Camp soon after his arrival

From left to right, back row: Sarginson, West, Gregson, Goard

Second row: Rainey, Yule, "Stock Keeper SO" (name not given), Pegrum Third row: Pauline, Ernest Dutnall, Harold Ratcliffe, Londoy

Front row: Perry, "chemist SO" (name not given), Lockwood, Larkin, Oliver Holding

Courtesy of Guy William Ratcliffe son of Harold Ratcliffe

There

is a break in the journal between the 31 May 1941 and the 2 November

1943. When it resumes he seems a completely different person, paranoid,

subject to delusions and obsessed with the belief that his fellow

internees are convinced he is a coward who abandoned his comrades while

he was with the British Army in May 1940. He wrote an account of the events in May 1940

which appear to have given rise to his delusions in his journal - see above. This

is detailed but rather confusing and not entirely convincing as an

accurate description of

what happened. The change is sharp and

inexplicable but he has an insight into his own condition and is aware

that his beliefs are not altogether rational.

Eventually, however, he persuades the camp authorities to treat him as a Prisoner of War (POW) rather than an internee and transfer him to Stalag VIIIB at Lamsdorf, the largest POW Camp in Germany, where he feels he rightly belongs. On the 1 July 1943 George Gregson was moved from the Stalag hospital to the German civilian asylum, Heil und Pflegeanstalt, at Loben.

Alarmed by the tone of his letters Gisèle wrote to the Red Cross on the 4 December 1943 (and again the next day) and received a reply from Miss E.M. Thornton OBE, the Director of its Prisoner

of War Department at St James Palace, London, on the 23 December which

quoted from the report of the doctor who had been treating him at Illag

VIIIH (Tost):

"Mr

Gregson had been in a distressed state of mind for some months so it

was decided to give him a change of surroundings and the advantage of a

thorough medical examination and treatment by sending him to another

hospital which is at Stalag VIIIB Lamsdorf. This was done in June."

A

further letter from Miss Thornton on the 10 February 1944 quoted from

the report of the doctor at Stalag VIIIB, Captain J.A. Mulligan RAMC:

"Mr

Gregson was admitted here on the 5.6.1943, and on the 1.7.1943 he was

transferred to a special hospital for nervous disorders. I saw him

there on the 4.11.1943. He has lost a lot of weight in the last three

years but now appears to be retaining his weight at a reduced level. He

eats well and has no bodily complaints. He has, however, delusions of a

persecutory nature, which give him great worry and keep him physically

over active. Apart from these delusions he talks quite naturally, and

takes a keen interest in his surroundings. He is very worried about his family, and is afraid that his past actions may harm his sons career."

He

was classified as "DU" (Definitely Unfit) by the International Medical

Commission which meant that he was likely to be included in any future repatriation of

civilians. A final letter

from Miss Thornton on the 23 February 1944 thanked Mrs Gregson for the

cheque for 10/- she sent to support their work, cautioned against

expecting her husband's early repatriation and expressed her pleasure

at learning that her son was enjoying "his new career as a cadet" and

added "it will give great pleasure to his father to know that he has

joined an officers training unit".

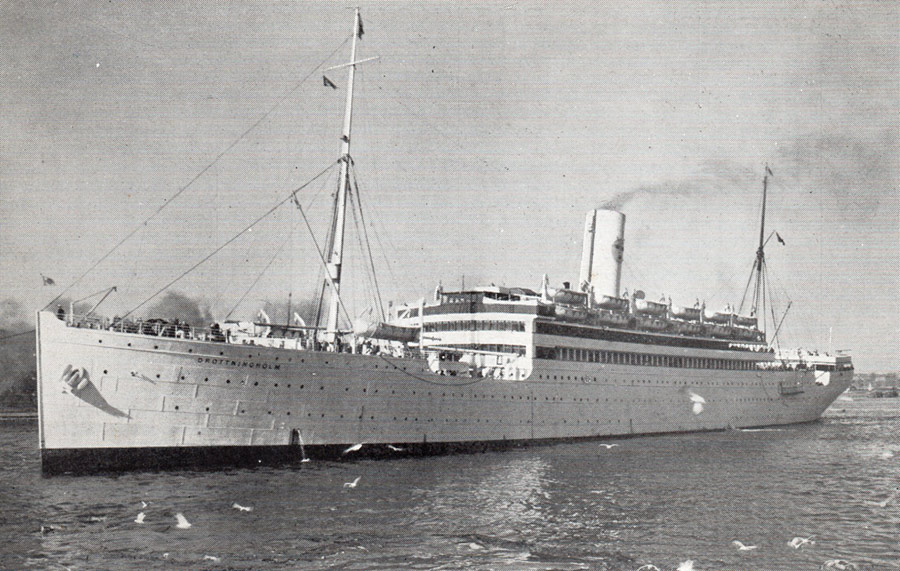

On the 27 June 1944 he left Loben for the

internment camp at Kreuzberg (Ilag VIIIZ) and a week later went by train to Vittel

in southern France. The fouth and final volume of his journal

begins on the 2 November 1943 at Loben and ends on the 29 July 1944

while on the train from Vittel to Lisbon in neutral Portugal with the

words "I wish I could think clearly!" On the 5 August he was repatriated to Britain leaving Lisbon on the SS Drottningholm for Liverpool where he wrote

to his wife from the City of Liverpool Hospital in Walton.

Gisèle described him "as being almost mad" but

once he was reunited with his family he made a good recovery and not

long after the war ended they returned to their home in Calais and he

once again became the practical hard working businessman supporting the

family. His two sons assumed joint control of the business when he

retired, one running the office in Calais and the other the office in

Boulogne. The events of May 1940 had a dramatic effect on all of them

but it did not destroy the family. George Arthur Gregson was 72 when he died at Calais in 1963. His wife lived

another twenty years and was 81 when she died in 1985. Their grand

daughter Anne Gregson has seen their stories are not forgotten

but regrets not having asked more questions about this critical period

in both their lives. Some parts of her Grandmother's letter and her Grandfather's journal are likely to always remain obscure.

A new edition of Les Oublies de 39-45: Le Rafle Des Britanniques (The Forgotten of 39-45: the Roundup of the British), Frédéric Turner's biographical dictionary of British subjects interned after the fall of France, containing 600 pages and 2,300 entries was published in April 2013 and can be ordered direct from the author.

You can read Anne Gregson's French translation of her grandfather's Journal on Pierre Ratcliff's site

Read about Gisele's escape to England aboard HMS Venomous on the 22 May 1940

Read the story of Tom Sarginson's internment and what happened to "Nell and the Girls"

Return to the Evacuation of British citizens from Calais in May 1940

The story of HMS Venomous is told by Bob Moore and Captain John Rodgaard USN (Ret) in

A Hard Fought Ship

Buy the new hardback edition online for £29 post free in the UK

Take a look at the Contents Page and List of Illustrations