As

German forces encircled the channel ports

British citizens living in Belgium and northern France desperately

sought ways of escaping before it was too late. The long established

British community in Calais was originally based on the traditional lace

industry which began two hundred years ago when three Nottingham men (Clark, Bonington and Webster) dismantled a Levers loom and smuggled the parts to Calais (Calais was

known as "Nottingham by

the sea"). The lace industry was mainly French owned by 1940 but there

were several other British firms in Calais. The best known were Courtaulds viscose

rayon factory which extruded molten rayon through spinnerettes to produce

multi filament fibres and

Brampton Brothers who made drive chains

for bicycles and chain driven machinery. Their senior managers were

often British and some employees were "tommies" who had

married French girls and stayed

in France after the Great War. There were 1,648 British subjects in the

Pas de Calais and 210 in Calais. There was an honorary British Consul and an Anglican church in Calais and the British community could buy their

groceries in the co-operative wholesale shop (la Coopérative Anglaise)

managed by Harold Ratcliffe, a British subject born in Calais who

served in the Great War and married a French wife.

As

German forces encircled the channel ports

British citizens living in Belgium and northern France desperately

sought ways of escaping before it was too late. The long established

British community in Calais was originally based on the traditional lace

industry which began two hundred years ago when three Nottingham men (Clark, Bonington and Webster) dismantled a Levers loom and smuggled the parts to Calais (Calais was

known as "Nottingham by

the sea"). The lace industry was mainly French owned by 1940 but there

were several other British firms in Calais. The best known were Courtaulds viscose

rayon factory which extruded molten rayon through spinnerettes to produce

multi filament fibres and

Brampton Brothers who made drive chains

for bicycles and chain driven machinery. Their senior managers were

often British and some employees were "tommies" who had

married French girls and stayed

in France after the Great War. There were 1,648 British subjects in the

Pas de Calais and 210 in Calais. There was an honorary British Consul and an Anglican church in Calais and the British community could buy their

groceries in the co-operative wholesale shop (la Coopérative Anglaise)

managed by Harold Ratcliffe, a British subject born in Calais who

served in the Great War and married a French wife.

Alors que les forces allemandes encerclent les ports de la Manche, des citoyens britanniques résidant en Belgique et dans le nord de la France ont désespérément cherché des moyens d'échapper de la zone avant qu'il ne soit trop tard. La communauté anglaise de Calais établie depuis longtemps était principalement liée à la fabrication de la dentelle commencée après les guerres napoléoniennes (Calais était connu comme "Nottingham sur Mer"). La plupart des fabricants étaient français en 1940. Mais Il y avait aussi plusieurs entreprises britanniques à Calais employant des citoyens britanniques. L'usine Courtaulds fabriquait des fibres de rayonne extrudé fondu à travers des filières pour produire des fibres à filaments multiples et les Frères Brampton produisaient des chaînes pour les cycles et les machines entraînées par chaînes. Leurs dirigeants étaient souvent britanniques et certains de leurs employés étaient d'anciens "tommies" qui avaient épousé des françaises et étaient restés en France après la Grande Guerre. Il y avait 1,648 sujets Britanniques dans le Pas de Calais dont 210 vivaient à Calais même. Il y avait un consul britannique honoraire, une église Anglicane et une église méthodiste; et la communauté britannique pouvait acheter leurs produits d'épicerie à la Coopérative Anglaise gérée par Harold Ratcliffe; fils d'un anglais émigré à Calais; Harold avait servi dans la Grande Guerre et avait épousé une française.

James George ‘Jack’

Hartshorn

(1900-1974), the Honorary British Consul in Calais, did his best to

help the British community escape from Calais. He was an

agent for the Norwich Union Assurance company and the Steam Navigation

Company as well as a wealthy lace manufacturer. His father had been the

British Consul before him.

Any distinguished visitor arriving in Calais

during the 1930s was bound to be greeted by Mr Hartshorn. When

interviewed by La Voix du Nord

in 1966 he recalled meeting the Prince of Wales and Neville Chamberlain

on

several occasions, greeting Mahatma Gandhi and Chancellor Dolfuss of

Austria in Calais and accompanying Emperor Haile Selassie on the ferry

to England when he fled Ethiopia.

James George ‘Jack’

Hartshorn

(1900-1974), the Honorary British Consul in Calais, did his best to

help the British community escape from Calais. He was an

agent for the Norwich Union Assurance company and the Steam Navigation

Company as well as a wealthy lace manufacturer. His father had been the

British Consul before him.

Any distinguished visitor arriving in Calais

during the 1930s was bound to be greeted by Mr Hartshorn. When

interviewed by La Voix du Nord

in 1966 he recalled meeting the Prince of Wales and Neville Chamberlain

on

several occasions, greeting Mahatma Gandhi and Chancellor Dolfuss of

Austria in Calais and accompanying Emperor Haile Selassie on the ferry

to England when he fled Ethiopia.

The man in plus fours in the photograph on the left (courtesy of Philip Emerson) taken outside the Anglican Church of the Holy Trinity on the Rue Moulin Brûlé, circa 1933, is probably Jack Hartshorn, the Chaplain's Warden. The man standing next to him in the bowler hat is Ted Emerson, a relative of Jack Hartshorn's who became Treasurer of the Restoration Fund in 1939. The war put a stop to that.The church was built in 1862 and nearly closed in 1934 due to declining attendance and finally closed when its Chaplain and the British community were evacuated from Calais in May 1940. In his short typescript history of the church published after its demolition in 1956 Jack Hartshorn wrote:

“Sunday, May 19th, the last Sunday Service was held in Holy

Trinity Church. The greater part of the British Colony, with the

Reverend McCullagh, were evacuated the following day.”

Herbert

McCullagh was 64 when he was ordained in 1932 after studying for the

Church at Bishops

College,

Cheshunt. He was the son of a Wesleyan minister and was born

at Eccleshall, Sheffield, in 1868 and

married Annie

Crowle, the daughter of a wealthy leather tanner and butcher from Cornwall, at

Birkenhead in 1907. He gave his profession as author in the

1911 Census when he was living at 36 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington,

the same address as his mother in law, by then a widow, but there are

no books under his name in the catalogue of the British Library. He

worked for the British Consular Service in Normandy, spoke French and

was for many years a lay reader in the Anglican Church. He trained for

the ministry on retiring and was ordained in 1932, the year that his

daughter, Marjorie Santo McCullagh, married Lewis Gustav Faulconbridge.

Herbert

McCullagh was 64 when he was ordained in 1932 after studying for the

Church at Bishops

College,

Cheshunt. He was the son of a Wesleyan minister and was born

at Eccleshall, Sheffield, in 1868 and

married Annie

Crowle, the daughter of a wealthy leather tanner and butcher from Cornwall, at

Birkenhead in 1907. He gave his profession as author in the

1911 Census when he was living at 36 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington,

the same address as his mother in law, by then a widow, but there are

no books under his name in the catalogue of the British Library. He

worked for the British Consular Service in Normandy, spoke French and

was for many years a lay reader in the Anglican Church. He trained for

the ministry on retiring and was ordained in 1932, the year that his

daughter, Marjorie Santo McCullagh, married Lewis Gustav Faulconbridge.

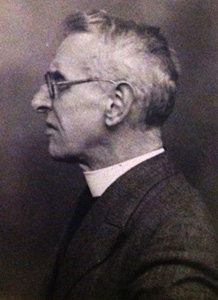

He was appointed Chaplain at Holy Trinity by The Colonial and Continental Church Society in 1934 and lodged at Jack Hartshorn's big house on the Rue de Vic for his first three years as Chaplain. He was conscientious and hard working though somewhat absent minded (his adopted grand daughter recalled that he frequently wore odd socks and had to be sent home to change them). He recorded attendance at services and other items of note in the Chaplain's Book (London Metropolitan Archives Ref. CLC/367/MS21470). The congregation included such well known British families as Arnett, Austin, Boot, Disney, Emerson, Kent, Maxton, Marvin, Prior, Saywell, Stubbs, West, Wood and Young. Congregations were small with as few as two at morning Communion but a few "Europos" helped boost the numbers recorded as attending services. The Rev McCullagh's photograph on the right was taken at Calais (Modern Photo, Rue Royale, Calais Nord) in June 1939 the month he attended the conference of the Chaplains of North and Central Europe in London and was presented to the King at Buckingham Palace.

2 July 1939

"The service taken by Lay Reader, Chaplain absent in England. Chaplain

presented to HM King George VI at Buckingham Palace, June 28th.

Afternoon of same day presented to Right Revd Dr Fisher, Bishop

Designate of London."

The Court Circular for the 29 June published in The Times

the following day announced that "The King received the Chaplains of

North and Central Europe who are at present in London for their annual

Conference. The Bishop of Fulham was present and the Gentlemen of the

Household in Waiting were in attendance." The Greater Britain Messenger,

the Society's quarterly magazine, reported that “a special privilege

was accorded to them by the consent of the King to receive them. Each

was introduced separately to His Majesty who was informed by Bishop

Batty about the work each chaplain was doing. The King’s interest was

evidently not forced. He had a kindly word of encouragement for each

individual.” The Times

reported that the retiring Bishop of Fulham [London] , the Right Rev

Staunton Batty, who was in charge of the CE Chaplains, was presented

with a gift of luggage by the 40 chaplains attending the Conference,

but any hopes he may have had of visiting his former charges were soon

dashed.

Two months later the outbreak of war was recorded by the Rev Herbert McCullagh in the Chaplain's book:

3 September 1939

"Service of Intercession for the Peace of the World during war crisis.

Address by the Chaplain (Rev H McCullagh) and special form of service. War declared same day."

The Rev McCullagh may have been living apart from his wife who died at

Westcliff-on-Sea, a suburb of Southend-on-Sea, Essex, on the 23 April 1940. A footnote in the

Chaplain's Book on

the 5 May states that the Chaplain is absent "through family

bereavement" and then on the 12th May "Return of the Chaplain".

The final service in Holy Trinity Church was held seven days later on Trinity Sunday,

the 19 May, and led by Mr Charles Hidden, Lay Reader. This story was to end tragically for the Chaplain. The Rev Herbert

McCullagh died on the 4 November when he was struck by a car during the

wartime blackout at Harlow, Essex, less than six months after his evacuation from Calais.

Back to events in Calais where the harbour city was crowded with refugees from Belgium trying to escape to England. Josef Massart was Belgium and unable to leave for England with his English wife Lillian May and their children, Loline and Raymond Massart. They thought it would be easier from Calais and they turned up on the doorstep of Jack Hartshorn's big house, known as the "Chateau Tourneur", at 95 Rue de Vic on Saturday the 18 May:

"We

arrived at Calais at 8 a.m. We deposited our luggage at a local café in

the rue Neuve. All of a sudden, our friends Ruby and Eugène appeared

and as Ruby was also English, we decided to visit the Consul together.

There we received the same answer: Ruby and Lilian were 'English born'

and could leave but Eugène and I would have to wait. The town was

crowded with refugees: small groups of people were on the pavements and

doorsteps, either eating or sleeping. It was impossible to find a place

to sleep. We returned to the Consul and explained our problem. The

friendly man listened to us patiently and offered to

let us spend the night at his home" (from the diaries of Josef Massart, photographed below in 1942).

The Massart

family were still guests in Jack Hartshorn's house when at 4.05 am on Monday 20 May:

The Massart

family were still guests in Jack Hartshorn's house when at 4.05 am on Monday 20 May:

"The

Consul ran into our room saying that he had received a telegram from

Lord Halifax saying that 200 Belgian refugees could leave immediately.

We were overjoyed! The Consul prepared the necessary papers and we

hurried to the harbour where the boat left at noon. The crew was

friendly and served us tea and sandwiches. Two hours and a half later

we arrived at Folkestone and after having been screened by the

authorities, we set foot on British soil!" From the Diaries of Jozef Massart.

The name of the ship on

which the Massart family with the Revd McCullagh and half of the

British community left Calais

that Monday has yet to be identified but it is almost certainly one

of the elderly V & W Class destroyers based at Dover, either HMS Venomous or one of its sister ships. Lt

Arthur

Taylor RNVR, the port naval officer at Calais, helped to organise the

evacuation (see "Unsung Heroes of Calais" by Colin Frame, in the London

Evening News and Star, 17 May 1965) and

recalled the names of the three V & W Class destroyers which gave supporting fire

and brought the refugees to England in the week before Calais fell on the 26 June: HMS Venomous, Verity and Whitshed. The elderly short range V & W

Class destroyers were ideally suited to make high speed dashes across

the Channel. Arthur Taylor recalled that there were lots of bottles of Champagne in the Wagon-Lits shed

and he gave their captains a welcoming glass on arrival. Fifty nurses from a military hospital also left

Calais that week.

HMS Venomous was ordered to Calais on the 21 May 1940

And returned with 200 British subjects - and vital equipment from the Sangatte "loop station"

Shortly after midday

on Tuesday the 21 May 1940 Venomous was ordered to bring back key staff and equipment from

the Sangatte "loop station". The loop station

at Sangatte a few miles west of Calais was a vital part of the

Dover Barrage, the minefields in the Dover Straits that prevented

U-Boats from entering the Atlantic via the English Channel by recording

the current produced by submarines passing

over loops of cable lying on the seabed between Sangatte and St

Margaret's Bay, Dover, and detonating mines from the shore or patroling destroyers and anti-submarine trawlers. Venomous berthed

alongside the Gare Maritime, Calais, at 13.15 to retrieve this vital equipment.

She also embarked 200 of the long term British residents

of Calais - including "Jack" Hartshorn, the Honorary British Consul.

The Gare Maritime was

an elegant nineteenthe century building where passenger

arriving from Dover boarded the train for their

onward journey to Paris or overnight departures to Istanbul, Berlin,

Rome, Trieste, San Remo, Monte Carlo, Nice and Bucharest. The

restaurant was known as one of the finest in Europe, the perfect place

to while away the time between arriving by steamer from Dover and

departure by Wagon-Lits. Before the war

British residents in Calais made the journey to Dover aboard the

luxury ferry Canterbury and boarded the Golden Arrow

for the 98 minute run to London. The station was thoroughly modernised in 1938-9

and reopened in June 1939 but the boat trains stopped running

in September and when HMS Venomous

berthed alongside the Gare Maritime the railway siding was occupied by

cattle trucks beneath which families sheltered from dive bombing

Stuka while waiting to board the elderly destroyer which took them to

safety in England.

This Michelin map of Calais in

1939 shows the Gare Maritime on the north side of the

tidal harbour and the Quai Paul Devot (22) on the south side connected by the Vetilland bridges

Steamers are berthed alongside the quay and the Golden Arrow is ready to leave for Paris

Apart from the equipment from the loop station at Sangatte the most valuable cargo on Venomous was £1.7 million pounds of Platinum spinning jets from

Courtaulds viscose rayon factory at Calais, Les Filles de Calais SA. Mr W.J. Allitt, the Financial

Director, organised the collection of the spinnerettes and brought them to the harbour in four jute sacks:

"We had half an

hours advice to catch the destroyer that brought us away from Calais

and that time was mostly spent in getting all our platinum together and

just throwing it in ordinary sack bags. There was no time to attempt a

count, a check, or a weighing of what we had accumulated. We merely

ransacked the safes, jet cabins, etc. and even the jets from the

spinning machines, uncleaned and full of viscose, were thrown as they

were in a sack, which should be easy to identify for viscose was oozing

out of it all the way to London."

Sixteen

year old John Esslemont was

born in Calais. His Scottish father had met his French wife during the

First World War and worked at the Courtauld's factory at Le Pont du

Leu.

Their luggage was packed but they went to work that morning and

received their last pay. John went to town that morning, "the streets

are crowded with Belgian refugees in cars, on bicycles, on foot". He

called on the British Consul, Mr

J. Hartshorn, to see if there was a ship to take them to England.

He was told there was no news of a ship, and went to the works but when

he returned he was told that a ship was leaving at 12.30

- and it was already 12.45!

John Esslemont' first language was French but he wrote this description of the days events in English:

"Mr Hartshorn tells

me that we should be at the Gare Maritime by 1 pm. I cycle as quick as

I can to my uncle's who takes his car out and we are soon speeding

towards Coulogne where we pick up my Mother and Father at home and back

we go to Calais, passing my uncle's to say goodbye to my aunt and my

grandmother.

They drove through the side streets of Calais Nord, encircled by waterways linked to the harbour by sea locks, and arrived at the open space (terre-plein) behind the Quai Paul Devot (number 22 on the map) where they could see HMS Venomous berthed alongside the Gare Maritime on the opposite side of the harbour. They sheltered in ditches (trenches) on the terre-plein when Stuka dive bombers flew overhead to attack the merchant ships berthed in the Bassin Carnot, the commercial harbour for Calais. The Vetilland road and rail bridges (see map) were impassable and they had to wait for the lock gates to close just after high tide (13.20) so they could use them as a foot bridge to the other side and board the waiting destroyer.

We then cut through

the side streets (the Boulevards being full of refugees) and we soon

reach the Maritime station. It is now 1.15 and the first thing we see

are all the British people from Calais and other refugees from Belgium

and the north waiting on the terre-plein Paul Devot. The ship is lying at the Quay of the station. She is a destroyer, HMS Venomous. The locks are shut [no, he means open] so we can't go near her yet.

There is an air

raid in progress and those who were there before us had to go into the

trenches. Not long after our arrival we hear the German planes coming

over the town, two of them are circling round half a mile away. So

everybody rushes to the trenches again and here come the planes roaring

overhead soon followed by the crashes of the bombs on the other side of

the Bassin Carnot, a few hundred yards away. They seem to drop nearer

and nearer but stop and the planes go off.

We remain in the

shelters because here come the sound of more planes and then for the

first time in Calais whistling bombs are dropped. Everybody tries to be

as near to the ground as possible; I make myself as small as I can and

I lower my head and involuntarily cover it with my hands. The noise is

dreadful and deafening, you always have the feeling that the bomb is

coming straight at you.

Then we are left

alone for a while. The lock gates were at last opened [an error, he meant closed] and we reach

the ship safely and we find that others had been on the Quay during the

raids. We go aboard, below deck in the sailors' mess. It's very hot,

everybody sits down round the tables and cups of tea are made

available. After a few minutes Jerry comes again and drops bombs on the

Quay and in the water all around us. The AA gun of the destroyer fires

at the plane. The ship shakes as if we were hit, however we are unhurt. The people on the Quay as the planes came over threw

themselves under railway trucks. When they came out the ground was covered with splinters of bombs and glass from the Maritime

Station. Then they came on board. I went down to the kitchen and was

drinking a cup of tea with William Heppeler and George Slater when the

alarm bell rang again.

This was our send

off from Jerry as the ship began to move and we were soon at sea and

three quarters of an hour later (we left at 2.30pm) we were speeding

past Dover at 25 knots. A sailor told me later that in the middle of the

Channel our speed was 30 knots. Now Folkestone is in view and we are

making a sharp turn and heading for the harbour lying empty before us.

When we step on the English soil we are amazed to find everything so

quiet and to see everybody going about as it was in Calais only a few

days before."

Pierre Ratcliffe was five when he left Calais on HMS Venomous with

his parents, Albert and Renée Ratcliffe, his sixteen year old

sister, Gisèle, and their cousin, Jack Ratcliffe. His father was

born in Calais, the son of a coal miner from Doncaster, but he had

British nationality and served in the Machine Corps in the Great War.

He worked for

an American company exporting lace and his wife was English by marriage and American by birth. Pierre and his sister

describe their escape to England aboard HMS Venomous on the 21 May 1940 and their lives in England.

Sidney and Robert West, distant relatives of Pierre Ratcliffe, also left Calais with their parents on HMS Venomous.

Their father, Frederick West, a staff Sergeant in the Royal Engineers from

Gillingham in Kent, had married Marguerite Louise Prudhomme, a bank

clerk, in 1918. He left the army but remained

in France and worked as a maintenance engineer at Brampton

Brothers. Sidney West describes the family's escape to England and their

mixed fortunes on arrival. They never returned to France.

In the confusion before Calais fell

husbands and wives were separated. George Gregson was a 49 years

old businessman and very overweight but he was a veteran of the last

war and decided to leave his French wife Gisèle at their home in Calais

and try to join the British Army. She set out for Dieppe in

the family's Rolls Royce but on reaching Camiers was turned back to

Boulogne where she

boarded HMS Venomous

and on landing at Folkestone on the 22 May was reunited with her two

sons who were at Kings School in Canterbury. Her husband was

interned at Tost in Upper Silesia and the family did not see each other

again until 1944. That week had a huge impact on both their lives. Gisèle Gregson's letter describing her escape to England and George Gregson's Journal describing his internment can be read on this web site.

Lt Peter

Kershaw photographed the refugees on the quayside waiting to embark,

some wearing bowlers and others looking more military in tin hats. AB

Sydney Compston recalled "during the air raids there were many women

and children on deck. Although exposed to

the greatest danger they were as good as gold - not a murmur."

Venomous left behind a member of its own crew, the ship's butcher. His absence was only discovered when he failed to appear at his action station when Venomous resumed its patrol after landing the refugees at Folkestone. He had been helping offload equipment at Calais and sought shelter beneath a railway wagon during the bombing raid and was left behind. He took shelter in a celler with plenty of liquid refreshments and when he sobered up he and some companions (not from Venomous) took an abandoned boat out of harbour, got back across the channel and he rejoined his ship a few days later.

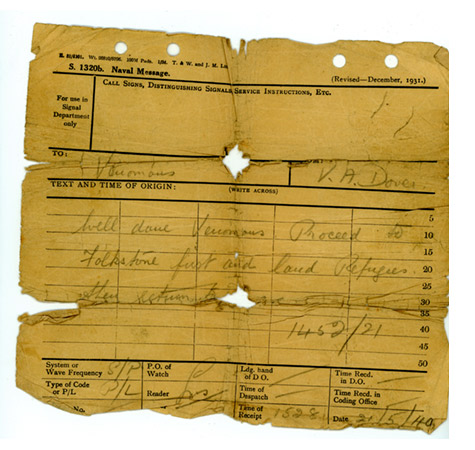

Naval Signal from VA Dover to Venomous, 14.52 on 21 May 1940

They were congratulated by Vice Admiral Ramsay at his headquarters in Dover Castle and told to land their refugees at

Folkestone (where arrangements had been made for the reception of refugees) before returning to Dover.

This signal was retained as a souvenir by George Speechley, Visual Signalman,

who joined HMS Venomous on the 31 July 1939 one month before the outbreak of war.

Astonishingly, HM Customs and Excise

demanded payment of import duty on the 26,000 platinum spinning jets

(spinnerettes) which Courtaulds and Venomous prevented from

falling into German hands.

John Esslemont

and his father went by

train to London and from there to Aberdeen where his grandparents

lived. His father soon got a job at Courtauld's factory in Preston and

John also worked there, as a mail boy and then as a junior clerk, but

as soon as he was old enough he joined the Royal Navy. He was

photographed with his parents while on leave from the Royal Navy

(right). In 1943 he was on HMS Balsam escorting Convoy KMS.9 from Londonderry to Gibraltar when he met up again with HMS Venomous.

She came out from Gibraltar to meet the convoy and accompany it into

harbour.

John was later stationed on shore duties at Cochin in India before

being discharged in 1946.

He returned to Preston to work for Courtaulds and in 1952 married his French wife, Claude. They returned to Calais in 1960 but moved to Vaudricourt near Béthune in the Pas de Calais in 1979. John Esslemont was 88 when he died in 2011.

Not all of Courtauld's British staff escaped rom Calais. Tom Sarginson

helped start the factory in 1926 but ignored advice to leave and stayed

behind with his English wife and three daughters. His youngest

daughter, Jeanne Gask, told their story in a book published in May 2015.

Five days later Calais fell to German forces

Wednesday 22 May

The following day Venomous escorted the Isle of Man ferry, Mona Queen,

taking the Irish Guards to reinforce the defence of Boulogne and

returned with 212 refugees including thirty two French orphans, their

teachers and four nuns.

Some like Gisele Gregson had come from Calais and finding the way west

blocked by advancing German forces were relieved to escape to

Folkestone aboard HMS Venomous. Her husband, George Gregson, was left behind and interned and she did not see him again until he was repatriated in 1944.

The V & W Class destroyers, HMS Vimy and HMS Wolsey, escorted the cargo ship City of Christchurch to Calais from Southampton with heavy motor

vehicles and tanks. The tank crews crossed from Dover on the passenger

vessels Canterbury and Maid of Orleans, escorted by HMS Verity,

The V & W Class destroyers, HMS Venetia and HMS Windsor, escorted the steamer Autocarrier from Dover to Calais where they arrived at 1200. The destroyers then acted as guardships at Calais.

Three requisitioned fishing trawlers

being used as minesweepers left Calais with evacuees including the families

of former soldiers employed by the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) to

tend the vast

cemeteries near the Belgium town of Ypres in Flanders. One 15 year old girl recalled being lent

a duffel coat by a tipsy fishermen on the Golden Sunbeam and being kissed on arriving safely at Folkestone.

The coasters Blacktoft and Theems arrived at Folkestone from Calais with about 600 civilian refugees.

Thursday 23 May

Demolition parties provided by the Kent Fortress Royal Engineers (KFRE) embarked at Dover on three V & W Class destroyers to blow up the oil reserves, locks and docks,

cranes and port facilities at the French Channel ports. Venomous

returned to Calais with a demolition party (XD.F) under Cdr C. S. B.

Swinley (but led by 2nd Lt Arthur Barton of the KFRE), HMS Wild Swan embarked the Dunkirk party XD.E (Cdr W. E. Banks) and HMS Vimy the Boulogne party XD G (Lt Cdr A. E. P. Welman DSO DSC Rtd.).

The Calais demo party were unable to get anywhere near the oil tanks

because there was heavy fighting already taking place but returned

safely to Dover.

On returning to Dover with the XD.F demolition party HMS Venomous left

for Boulogne where she joined several other V & W destroyers

waiting offshore to evacuate the Welsh and Irish Guards taken there the

previous day.

HMS Vimiera escorted the cargo ships Ben Lawers and Kohistan from Southampton to Calais where they arrived at at 1545 hrs carrying motor vehicles, ammunition and fuel.

HMS Windsor escorted the requisitioned passenger ships Archangel and Royal Daffodil, transporting the 30th Brigade from Dover to Calais, and the hospital carrier Paris, escorted by HMS Wolseley, entered the harbour to embark casualties.

The drifter Shipmates left Calais for Folkestone with 136 civilian evacuees.

HMS Wessex, Vimiera and Wolfhound bombarded German positions around Calais.

HMS Wolsey and HMS Windsor departed Dover at 0935 with demolition parties for Le Havre and were then sent to Calais before returning to Dover.

The City of Christchurch left at 1310 for Southampton with troops, wounded, nurses and most of the families

of former soldiers employed by IWGC at Ypres in Flanders. After

being diverted from Dover it arrived in Southampton the following

afternoon. More than half the 527 IWGC staff reached Britain from

Calais or Boulogne (where its office was located nearby at Wimereux).

Destroyers Wolfhound and Verity were ordered at 1339 to bring ammunition to Calais for the British troops encircled there and HMS Verity landed a Royal Marine Guard to protect the harbour.

Friday 24 May

The Ben Lawers left at 0630, the "latest it could make it out of harbour on the falling tide" with the wounded men from a hospital train on the quayside.

The merchant ship, Kohistan,

left Calais at noon, the last transport ship to leave (Lt Arthur Taylor

RNVR, the STO at Calais, is believed to have been aboard).

See Flames of Calais, a soldier's battle; by Airey Neave (London: Hodder and Staughton, 1972)

The private diary of Col R T Holland, G.H.Q. A.G. (NA Catalogue Reference: WO 217/2) describes how the Gare Maritime became the HQ for British forces:

About 1430 hours

owing to the proximity of enemy armoured fighting vehicles at the

Western exits of the town, the combined Brigade and CALAIS H.Q. moved

to crowded cellars in the GARE MARITIME. The Signal Office at the Civil

Post and Telegraph Office was evacuated at the same time.

From now onwards our only communication with higher authority was by

wireless to DOVER. Commodore GANDIE (an error, should be Gandell), ROYAL NAVY (Principal Sea

Transport Officer, Channel Ports) had established himself at the GARE

MARITIME at this time; this officer left for ENGLAND later.

This diary was compiled in July, 1943,

while Col Holland was a POW at Oflag IX A/H (Spangenberg) from such

sources as were then available.

HMS Wessex, HMS Vimiera and HMS Wolfhound and the Polish Navy destroyer ORP Burza were bombarding German Army forces advancing on Calais when they were attacked by 27 Junkers 87 dive bombers at 16.30. HMS Wessex (Lt Cdr W. A. R. Cartwright) was struck by three bombs between the funnels and sunk. The survivors were rescued by HMS Vimiera.

Saturday 25 May

Vice Admiral James Sommerville RN

(1891-1949) arrived In Calais at 0130 and informed Brigadier Nicholson

of Churchill's decision that there would be no evacuation of troops and

Calais must hold out to the end:

Vice Admiral Sommerville embarked on Verity with 80 Marines and some ammo and sailed from Dover at 2330. Arrived at Calais at 0130 on the 25 May. Fired on by German 5.9 inch battery. Ship straddled by three salvos and some men injured by splinters. Ship moved to safer billet. Met by Cdr W.P. Gandell RN and taken to Brigadier Nicholsons HQ in cellar under railway station full of exhausted officers and men. Woke Nicholson who asked if we had come to take them off. He had to tell him this was not the case, PM had telephoned that it was essential for garrison to fight till the last to hold up advance of Germans threatening to cut BEF from Dunkirk. Nicholson appeared quite unperturbed. Had expected these orders. Planned to withdraw to Citadel, but wanted to retain Verity and/or Wolfhound as comms link. Somerville said that they needed to go as otherwise Germans would destroy them at dawn. Told Brigadier about an intact wireless van in the Station and gave him working frequency for Dover. Somerville found Verity had already sailed, and left in Wolfhound at 0300, arriving Dover at 0430.

This precis of Vice-Admiral Sommerville's visit to Calais was made by Frank Donald from the Sommerville Papers in the Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge, which were published by the Navy Records Society, vol. 134 (1995).

Lord Howe later got alongside the quay to unload ammunition and medical supplies.

HMS Wolfhound disembarked

ammunition for the British troops and returned with Vice Admiral

Somerville after his meeting with Brigadier Nicholson.

At 0515 Brigadier Nicholson moved to

the Citadel where he established a joint HQ with the French in a cellar

of a block of buildings.

Sunday 26 May

A small fleet of trawlers, drifters, river launches and yachts had set out from Dover the previous evening in case the evacuation of Calais was ordered and arrived off the French coast at 0140 hrs. Although no evacuation order was given the trawler Botanic brought home ten troops snatched from the north jetty by the river launch Semoris, the trawler Arley left for Folkestone with 110 French soldiers and the yacht Conidaw which entered Calais under heavy machine gun fire and grounded as it left on the falling tide reached Dover at 15.40 with 165 aboard.

At 2153 hrs the yacht HMS Gulzar

found the port to be in the hands of German troops but left with

Commodore Wilfred P. Gandell (1887-1986), the PSTO aboard: "After she slipped her hawsers she

was hailed by an English voice and went back to pick up fifty soldiers,

finally clearing the harbour at 0100 on the 27th, when the whole town

was in German hands" (From Full Circle: Admiral Sir Bertram Home Ramsay; by W.S. Chalmers. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1959). For more about HMS Gulzar see Impossible Escape from Calais.

Brigadier Claude Nicholson (1898-1943)

surrendered in the Citadel at 1600. His private Diary is in the National Archives at Kew, WO217/1.

He was the Senior British Officer (SBO) at Oflag IX A/Z , Rotenburg,

and took his own life on 26 June 1943, the anniversary of the

surrender. He had been prone to depression about events at Calais and

this may have been made worse in May 1943 by

German attempts to expose Russian responsibility for the massacre of

Polish army offices by making the SBO in Germany a witness to the

excavation of the

mass graves found at Katyn.

A Hard Fought Ship and The Forgotten of 39-45 were exhibited at the "Expo Fair" in Calais on the 14 - 16 June 2013.

The stand was organised by Anne Gregson (centre) whose grandmother escaped to England aboard HMS Venomous but whose grandfather was interned at Tost

From left to right: BIll Forster, publisher of A Hard Fought Ship, Antoinette

Boulanger who documented the lives of the women of the Pas de Calais

who resisted the German occupation, Anne Gregson, British born Anne Fauquet and Bill's wife, Reinhild Balcke.

Children acquire the nationality of their country of birth but

in France they can renounce

French nationality on reaching the age of majority, eighteen, and take

the nationality of their father. Before the Great War many children

born in France to British subjects chose to do this. Most holders of

British passports were able to leave Calais

before it fell to German forces but some French born British subjects,

including Albert Ratcliffe's three brothers, decided not to leave but

to stay and and risk internment - or worse - when German forces

occupied Calais.

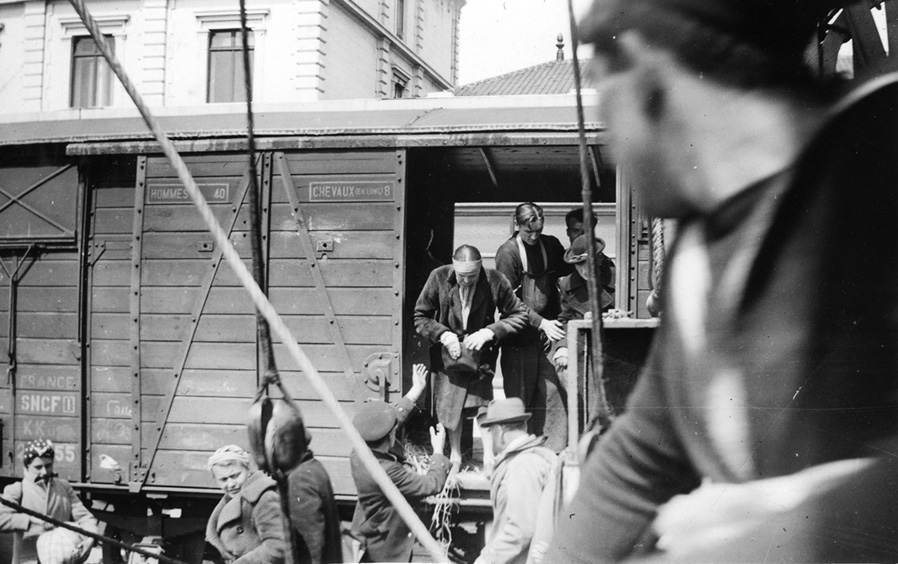

On the 31 December 1939 "The Census of Foreigners" recorded that there were 1,648 British people, and

people of British descent, living in the

Pas-de-Calais of which 751 were men, 699 women and 198

children under the age of fifteen. Of

these 210 were living in Calais itself (120 men, 88 women and 2

children). In July and August 1940, almost all the men over

17 were arrested and a month later deported in animal railway

wagons to camps in

Germany. Many of these young men took British nationality on reaching

the age of eighteen and as a result remained interned for the rest of

the war.

On the 31 December 1939 "The Census of Foreigners" recorded that there were 1,648 British people, and

people of British descent, living in the

Pas-de-Calais of which 751 were men, 699 women and 198

children under the age of fifteen. Of

these 210 were living in Calais itself (120 men, 88 women and 2

children). In July and August 1940, almost all the men over

17 were arrested and a month later deported in animal railway

wagons to camps in

Germany. Many of these young men took British nationality on reaching

the age of eighteen and as a result remained interned for the rest of

the war.

These figures are taken from Les Oublies de 39-45: Les Britanniques internés à Tost, Kreuzberg, Giromagny et Westertimke (The Forgotten of 39-45: the Britains interned at Tost, Kreuzberg, Giromagny and Westertimke, ISBN 978-2-9538021-1-5). The second edition of Frédéric Turner's biographical dictionary of British subjects interned after the fall of France (on left) with 604 pages and 2,300 entries was published in April and can be ordered now.

The Germans tried to stir up hatred against the British living in Calais. One local paper, Le Petit Calaisien, followed up an anti-British article on the 22 June 1940 by publishing on the 14 July the proclamation by

the German authorities that any British subject over the age of eighteen failing to report to

the Town Hall would be assumed to be a spy and "judged accordingly", i.e. shot.

Regardless of

place of birth and nationality their names alone usually indicated their country of origin making it difficult to escape

detection and arrest. Pierre Ratcliffe gives this short list of some of those interned:

John Barribal, born 1885, mechanic; Ernest Brimble, born 1888, hotelier; Elise Brown, born 1881, housewife; Frederick Brown, born 1883, tulliste. Eugene Buck, born 1900, housewife; Melvyn Cannings. born 1896, shopkeeper; Ernest Dutnal, born 1888, businessman; Gregson, born 18??, merchant; George Grey, born 1901, Company Director; Fernand Grey, born 1901, factory worker; William Grey (released 1942 but forbidden to return to Calais); Jacqueline Harris, born 1926, typist; Agnes Hazeldine Agnès, born 1864; Henry Hicks; Charles Hicks; Oliver Holding, born 1899, labourer; Luie Kearton; Albert Larkin, born 1890, interpreter; Leod Alexander Mac, born 1888, employee; Denise Leod Mac, born 1896, employee; Elijah Mynheer, born 1880, labourer; Albert Perry, born 1880, tulliste; Harold Ratcliffe, born 1896, owner of grocery shop; Reginald Rayney Reginald, born 1897, employee of Brampton Brothers; Marguerite Spencer, born 1888, housewife; Frank Spencer, born 1891, hotel manager; Albertine Staples, born 1886, housewife.

After

the liberation of France and the end of the war in Europe some of the French born British citizens who left Calais in May 1940

returned to France where they had homes, friends and in some cases

families. "Jack" Hartshorn, the British Consul

who did so much to help his fellow citizens escape from the besieged

city and left himself a day later on HMS Venomous

decided to stay in London where he lived at 24 Holland Park, a

magnificent detached house. He left Calais a bachelor in his forties but

met and

married Margaret E. Rayner in England. During one of his many postwar

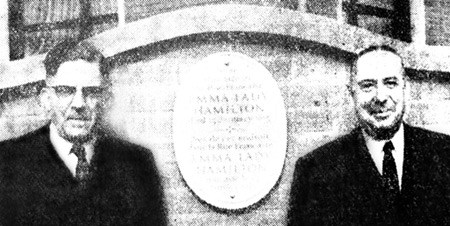

visits to Calais in 1958 he was photographed (on left) with the British

Vice Consul, Mr Leete, at the unveiling of a plaque in memory of Lady Emma Hamilton

(1765-1815), Nelson's mistress, at the junction of Jean de Vienne and

Philippine de Hainaut streets, near the site of the house where she

died in poverty. Jack

Hartshorn died at Marlborough,

Wiltshire, in 1974, but was buried in the Calais North Cemetery where

his father, his predecessor as British Consul, is also buried.

After

the liberation of France and the end of the war in Europe some of the French born British citizens who left Calais in May 1940

returned to France where they had homes, friends and in some cases

families. "Jack" Hartshorn, the British Consul

who did so much to help his fellow citizens escape from the besieged

city and left himself a day later on HMS Venomous

decided to stay in London where he lived at 24 Holland Park, a

magnificent detached house. He left Calais a bachelor in his forties but

met and

married Margaret E. Rayner in England. During one of his many postwar

visits to Calais in 1958 he was photographed (on left) with the British

Vice Consul, Mr Leete, at the unveiling of a plaque in memory of Lady Emma Hamilton

(1765-1815), Nelson's mistress, at the junction of Jean de Vienne and

Philippine de Hainaut streets, near the site of the house where she

died in poverty. Jack

Hartshorn died at Marlborough,

Wiltshire, in 1974, but was buried in the Calais North Cemetery where

his father, his predecessor as British Consul, is also buried.

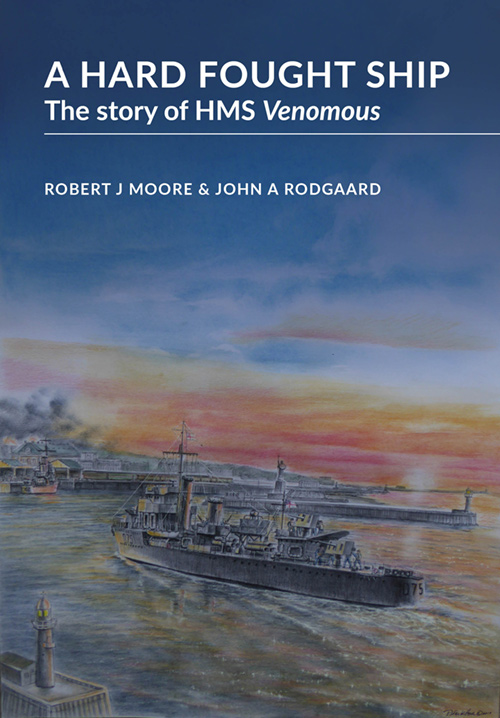

The story of HMS Venomous is told by Bob Moore and Captain John Rodgaard USN (Ret) in

A Hard Fought Ship

Buy the new hardback edition online for £35 post free in the UK

Take a look at the Contents Page and List of Illustrations