There are four first hand descriptions of the voyage of the Zeemanshoop from Scheveningen to England that evening. Two are letters written in 1946 by Lou Meijers, a member of the "crew" of four students, and Wim Belinfante, a Dutch Jewish refugee, to H. Th. de Booy, the Secretary of the Dutch Lifeboat Association, the NZHRM. Both letters have been translated into English by Radboud Hack. Follow these links to read Lou Meijers letter in Dutch or English and Belinfante's letter in Dutch or English. The well known account of the voyage in his book about the wartime exploits of the Dutch Lifeboats, Tusschen Mijnen en GrondzeeŽn (G.A. van Oorschot, 1947) is mostly based on these letters. Lou Meijers and Wim Belinfante were interviewed on Dutch Radio in 1989 and can be heard describing the voyage on a Podcast.

A more detailed description of the voyage was written in 1981 by Harry Hack, the "Captain" of the four man crew in order to be accepted as a member of the Society of Engelandvaarders and has been translated into English by his son, Radboud Hack. This remained in the family and has not been published until now. It can be viewed here in Dutch and in English. Finally, Loet Velmans, a seventeen year old school boy in 1940, described the voyage in a chapter of his book, Long Way back to the River Kwai (Arcade, 2003, 2011) which has been published in Dutch as Terug naar de River Kwai, Herinneringen aan de Tweede Wereldoorlog (Walburg Pers, 2005).

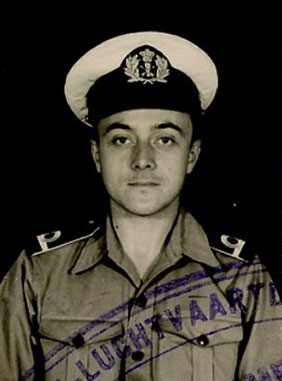

At 1.30 pm the Germans bombed

the heart of Rotterdam and within five hours German troops occupied the

city. Two students at Delft University, Karel Dahmen (on left) and Jo Bongaerts (on right in RAF uniform, courtesy of NIMH),

watched the huge column of smoke as Rotterdam was bombed from the window of their

student digs and were eating their supper when they heard the 6 pm

radio broadcast of the surrender of Dutch

forces. They immediately decided to cycle to Scheveningen and try and find a boat to England. Others were making similar plans.

At 1.30 pm the Germans bombed

the heart of Rotterdam and within five hours German troops occupied the

city. Two students at Delft University, Karel Dahmen (on left) and Jo Bongaerts (on right in RAF uniform, courtesy of NIMH),

watched the huge column of smoke as Rotterdam was bombed from the window of their

student digs and were eating their supper when they heard the 6 pm

radio broadcast of the surrender of Dutch

forces. They immediately decided to cycle to Scheveningen and try and find a boat to England. Others were making similar plans.

Harry

Hack, a 26 year old student of mechanical engineering at Delft

University, was having his supper when his landlady burst in with the

news of the surrender. It was 7 pm and impulsively, without further

thought, he decided to go to England. He set out for Scheveningen on a

borrowed bicycle, shouting out “I’m going to England” as he passed the

Air Protection Post where he was supposed to be on duty and abandoned

the bike when a fellow student gave him a lift in his car. He met Karel

Dahmen and Jo Bongaerts at the fishing harbour where huge sums of money

were being offered by Jewish refugees to any fisherman prepared to

ferry them to England - but without any takers.

Harry Hack suggested taking one of the two lifeboats they could see on the opposite side of the outer harbour, the north west side. "They think there is no chance of this so I go on my own. I jump onboard the smallest lifeboat, the Prins Bernhard. The engine room is padlocked. Let's see if I can get a metal saw from the nearby fishing boat." Karel and Jo changed their minds about the lifeboats and take a look at the Zeemanshoop. It was also padlocked but a steel helmeted sergeant in the Marechaussee,

a military police service, wants to come with them. They use the

bayonet on his rifle to break

the lock on the hatch to the engine compartment. The sergeant has not

been identified (but Otto Neurath described him in a letter to the

architect Josef Frank, 22 September 1942, as "a Jew who wanted to fight

Hitler from England") was accompanied by a woman, his sister or his

wife. They were joined

by Lou Meijers, a first year medical student who had cycled 200 kms

from Groningen.

Karel Dahmen and Jo Bongaerts had been joined by two high school students. Loet

Velmans and his cousin

Dik Speijer, had cycled from their parents homes in the Belgian

quarter of Scheveningen to get a boat to Zeeland where fighting was

still taking place but now decide England was a better option. Loet

told a young boy that if he delivered a note to his parents he could

keep his bike. One of the students saw this transaction, said they had found a lifeboat and asked, "Want to come along?" The

two school boys were flattered to be asked and immediately agreed.

A large crowd had gathered, eager to get to England. Most were Jewish and many were from Germany, refugees for the second time. They included whole families, men, women and young children, some with suitcases, and all smartly dressed. They "all wore or carried over their arms a beige or navy blue raincoat - in 1940 casual clothes were not yet in fashion" (Loet Velmans). A gangway was let down and the boat quickly filled with eager people crammed tightly together on deck.

The

Zeemanshoop in the Vissershaven (fishing harbour) at Scheveningen and an aerial photograph showing the layout of the inner and outer harbours

The engineer probably jumped ashore on the Adrian Maasplein

Non of the students knew anything about marine diesel engines.

Jo and Karel went off to seek help leaving Meijers in the engine

compartment. When the fisherman refused to help Harry break into the Prince Bernhard he tries the Zeemanshoop and finds it open. Harry had been an apprentice engineer on a voyage to the Dutch

East Indies and immediately took charge, upsetting Meijers by asking him

not to touch anything and to sort things out on deck. The engine was a 2-cylinder Kromhout MD (44 hp) made in Amsterdam, a hot bulb engine started

by

heating with a hand held blowlamp. Harry knew the basic principles but

had no practical knowledge of how it worked. Fortunately, he had some help:

"While I am trying to figure out how to do his, some help arrives,

apparently a "fisherman engineer". "I'm willing to help you but I will

not go with you". He puts on the pre-heater (with a blowlamp) and after

a while the engine starts" (Harry Hack).

A

hand written note on Meijers letter to the ZNMRH reads "The

engine was started by two Scheveningen men J. Pronk and Martinus

(Tinus) Rog." In

1940 Tinus Rog was a nineteen year old fisherman living with his

parents and when they heard the news of the surrender they told him to

check that that the family's fishing boat was safe and to make sure

that it wasn't stolen. He borrowed his girl friend's bike and cycled to the harbour:

A

hand written note on Meijers letter to the ZNMRH reads "The

engine was started by two Scheveningen men J. Pronk and Martinus

(Tinus) Rog." In

1940 Tinus Rog was a nineteen year old fisherman living with his

parents and when they heard the news of the surrender they told him to

check that that the family's fishing boat was safe and to make sure

that it wasn't stolen. He borrowed his girl friend's bike and cycled to the harbour:

It

was swarming with people. There were lots of Jews and

soldiers walking round. A suitcase fell open and he saw it was

full of gold and silver but thought that was none of his business. After a while somebody approached and

asked him: "Are you from Scheveningen? Can you start an engine" He said

he could and went on board the Zeemanshoop. Tinus asked him, "Do you have a permission to take

the lifeboat" and they said they did. He

started the engine and told one of the men to make sure to top up the

lubricating oil when it got low and told them how to do it. He also asked, "Do you know how to

set the course?" They didn’t so he explained how to use the compass and

told them to stick to NW. They wanted to know if he would like to come with

them but he said no and was dropped off at the end of the breakwater

(known as the ‘pipe’) on the right hand side and had to climb over a high fence

to get back. He was very upset to find the bicycle which belonged to

his girl friend had been stolen

but somebody saw who took it and gave him the address. He went there

and

the man warned him, "Don’t tell anyone what you did because if the

Germans

find out, you will be in big trouble". He didn’t even tell his parents

or his girl friend until after the war. Not long

after the war ended someone came by and thanked him. It was one of

the passengers but he does not remember the name. (Tinus Rog was

interviewed and photographed at his retirement home by Lucas Ligtenberg

in May 2014).

There are also other accounts of how the engine was started. Jaap Pronk, the skipper of the present lifeboat at

Scheveningen, a modern RIB (Rigid Inflatable Boat), described by

e-mail how the crew of the Zeemanshoop

agreed that the students could take the lifeboat to England and one of

them, Van Kampen, helped them start the engine but would not accompany

them for fear the Germans would take his family hostage. After

heating with the blowlamp the first cylinder began firing and Harry was told "you can start the other one yourself".

The sergeant fired a warning shot

over the heads of the crowd on the quayside and they prepared to leave.

At that moment a taxi drew up and out stepped Loet and

Dick's parents plus two uncles and aunts. 'No room', said one of the

students. 'But it's our parents' Dick and I yelled." (Velmans). Loet and Dik's families were Jews who had lived in Holland for several generations. They

were allowed on board and the Zeemanshoop

cast off. Dr Simon Weyl (Weijl) made a desperate attempt to leap aboard, fell in the

water and was hauled onto the deck by his friends. He was the last

passenger to join the Zeemanshoop.

Karel Dahmen took the helm, "the Zeemanshoop

was not in the inner harbour [as stated by Meijers] but in the so

called second harbour and when I steered the boat I

had to make a right turn that brought it directly between the

main harbour heads". "Chug-chug-chugging, we leave the harbour. As we

pass between the jetties the engineer jumps ashore. 'What course?'

'North-west' he shouts, the last words of advice from our

country." (Harry Hack). The time recorded on the sea chart during the

voyage was 21.00 (or 22.00 "daylight saving time"), the sun was setting

and it was soon dark. The women sat on bench seats either side of the raised cabin and

the men stood, holding onto the rail, staring out to sea. It was cold but the sea was calm. Their only provisions

were several bottles of rum, a small amount of drinking water and "a

dozen or so chocolate bars which one of the parents had prudently

packed to keep his child quiet" (Velmans).

There was a blackout but

the lighthouses came on at midnight. On the horizon they could see the

flames of Rotterdam burning after being bombed (thousands were killed

and many more lost their homes). Some

passengers had brought poison to kill themselves if captured (Kurt

Munzer) and in later years Marie Neurath (neť Reidemeister) and Freda

Munzer recalled discussions on whether the time had come to take their

poison.

"I

have quite a vivid memory of Dr. Neurath that night. He was sitting in

the stern, just behind me when I was steering. He asked me: 'Wo sind

wir jetzt / Where are we?' I said 'I don't know'. Said he: 'Aber Sie

kŲnnen doch Ihre Position ausrechnen? / But you can work out your

position? I explained that I had not learned how to do this. He said:

'Ach so, ist das nicht so leicht? / Ahr, that's not so easy then?' A

little later, he asked: 'Und wie viel ist der Fahrpreis? / And what is

the fare?' When I said that there would be no charge, he remarked: 'Ah,

das ist sehr gut / Ahr, that's very good'." (Karel Dahmen). Otto Neurath,

an internationally renowned

Viennese philosopher and social reformer in his late fifties, "was a

very compelling character - a big jolly man, over 6 foot, red haired

(though not so much by then) with a loud voice" (Michelle Henning).

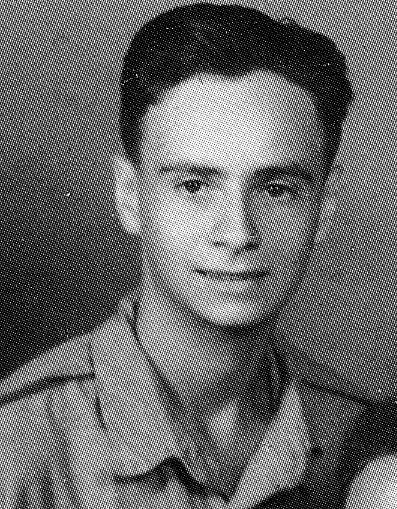

Harry

Hack (on left) was very much in command and appeared to enjoy the

challenge of getting the lifeboat and its passengers to England. If the weather were to change the over crowded small boat

could be in difficulty and he asked Marien de Jonge, an experienced

yachtsman, to take the helm.

Harry

Hack (on left) was very much in command and appeared to enjoy the

challenge of getting the lifeboat and its passengers to England. If the weather were to change the over crowded small boat

could be in difficulty and he asked Marien de Jonge, an experienced

yachtsman, to take the helm.

With this problem out

of the way he returned his attention to the engine. It was running on

only one cylinder and in danger of over heating. When this happened the

engine had to be disengaged from the propeller, the

lifeboat then lost way, drifted and would not respond to the

helm. They appeared to be drifting closer to the shore and the

passengers became nervous and restless.

Loet Velmans describes what happened next:

"A man with a double-barreled name and the title Jonkheer signifying membership of the Dutch nobility started bellowing at the top of his voice, demanding that we return to port - 'for the sake of the women and children'. It started as an open debate and he had some support from the older passengers but then the argument got ugly, there was a lot of pushing and shoving. When I realised that what we were talking about involved the risk of our being arrested by the Gestapo, I began to shake. This was a serious business - our very survival was at stake."

"Then

a lone voice, timid and hesitant, suggested a vote. Before the polling

could start, however, one of the students finally took charge and shouted 'If you don't like it, you can swim back'. The

mutiny subsided as quickly as it had began" (Loet Velmans)

Harry Hack came on deck from the engine compartment and describes how:

... our 'first mate' pours out his heart: "We don't have a ghost of a chance to arrive at the other side. We better go back."

Our answer is brief and to the point: "We go on!"

"In that case I cannot any longer accept responsibility for what will

result in a collective suicide." He rejoins the passengers again.

Marien de Jonge had

left behind his wife and two week old son to go to England and fight

for Queen and Country but as an experienced yachtsman he knew the

weather in the North Sea could quickly change and with the lifeboat so

overcrowded there was at the very least a danger of being washed

overboard. He thought the wiser option would be to join the remnants of Dutch forces fighting on in Zeeland.

Was

Marien de Jonge right to be so concerned? Harry Hack's son, Radboud,

who initially trained as a naval architect before switching to aeronautical

engineering, thinks he was. When the Zeemanshoop

was launched in 1925 it was found to be significantly less stable than

comparable lifeboats and the NZHRM corrected this by adding 2.2 tons of

ballast to the keel increasing the

weight from 18 to 20.2 tons. The 46 passengers would have added another

3 tons to the weight of the lifeboat and, critically, this was at deck

level. Its stability was now far less than the minimum specified by

the NZHRM a few years earlier. For the technically minded, the NZHRM

initially had a metacentric height of 41 cm and after adding the

ballast this increased to 50 cm but Radboud Hack's calculations show

that on the 14 May 1940 the weight of the passengers reduced the metacentric height of the Zeemanshoop to only 33 cm.

De Jonge would not have known about this but would have sensed that the

lifeboat was unstable by the time it took to right itself after applying the helm and would

know that it was likely to become "een varende doodskist" - a floating

coffin - should the weather change. On the other hand the Jewish

passengers had nothing to loose, some

intended to poison themselves rather than be captured and Otto Neurath

had joked, “If we don’t find a boat I’m going on a piece of wood”.

Harry Hack may have

thought that "As long as the weather is good, we have a chance of

reaching England" while Marinus de Jonge was thinking "We are still

close to shore and if we head SSE we can safely reach the Dutch forces

fighting on in Zeeland". Once de Jonge was overruled he curled up in

the cabin area and went to sleep (Karel

Dahmen) and Lou Meijers who had learned to "steer a bit on the holiday

camps of the NJV" took over the helm.

This incident made Harry Hack think:

"First,

we had to face the fact that the passengers' nerves might break. We had

a doctor on board. He understood the situation and promised to keep an

eye on people. I asked him to let me know at the first sign of panic.

We could not afford to let things get out of control and sacrifice the

whole voyage for one person. Next, we decided to give people jobs to do

to take their minds off things: a look-out for floating mines and so

on. But: stay where you are! Second, we decided to make a list of all those onboard. Our doctor

reported 'no worries at present'." (Hack)

What significance

should be attached to Harry Hack's underlined words of caution "stay

where you are!" Did he realise that any attempt by the passengers to

gather on the same side of the lifeboat if a mine was sighted might result

in a capsize?

And who was this

doctor? There seems little doubt that it was Dr Simon Weijl (Weyl), who

fell in the water and had to be dragged aboard soaking wet, the last

person to join the Zeemanshoop

before it left Scheveningen. He was desperate to join his assistant

Liselotte Mayer and her German Jewish husband, Vicor Meyer, on the Zeemanshoop. Simon Weijl was a 46 year old psychiatrist

and neurologist with a practice in The Hague. His love for Liselotte

compelled his decision to leave the Netherlands. He was uniquely

qualified to assess how the passengers were coping with stress and

whether their behavious might endanger both them and the lifeboat.

Lou Meijers recalled that the list of passengers was made:

"...

because there were many German speakers among them. Later we copied

this list onto the back of a Chart of the Dutch Life Boat Stations. We

found this chart only after we had broken into a locker containing

emergency flares." (Meijers)

This list of names on the back of the chart of the Dutch lifeboat stations was the key to tracing the families of the passengers and crew of the Zeemanshoop.

Harry Hack was relieved when "the propeller can be engaged again and the cooling water valve

opened a bit more. We drifted many more times." (Harry Hack).

The compass sticks, its light fails and they steer by the Polar Star

and towards a star near the horizon. "The night passes. On deck

everything remains quiet. The engine is running steadily."

At about 04.30

the next morning, dawn, the stars fade away. Harry Hack goes on

deck, steps outside the rail and edges his way round the lifeboat walking along

the outside fender, the only place to put his feet:

"The

boat is low in the water, too low in fact. Water is splashing over the

freeboard. Meyers hands oilskin coats to those who tend to get wet. The

sun rises and starts warming us. We ought not to complain. It looks as

if it will be a beautiful, if uncertain, day. (Hack)

"The

weather remained excellent and the sea as calm as one could wish. This

was a very lucky fact, because, if the weather had been even a bit

worse, without any doubt we would have lost some people. At dawn, we

started to redistribute the deck load as we were a bit nose-heavy. Also

the two man-holes were inspected, and from them emerged very useful

things like oilskins and emergency rations. The rations were stored

safely and well in the engine room because we had no idea how long the

trip to England would take, and the emergency rations were only to be

used in case of a real emergency. From the beginning there was a great

need for liquid. (Meijers)

"At

daybreak a formation of bombers flew over us. We assumed they were

German though they were too high for us to gauge whether they were

friend or foe. An elderly couple told the sergeant that he had better

hide his rifle under his coat; if he didn't we might be mistaken for a

military target. The unidentified aircraft ignored us. They were

undoubtedly after bigger game. The

sun rose in a breath taking pink dawn" and "except for the children

nobody complained of hunger or thirst; we were too scared, too excited

or both." (Velmans)

The passengers had

stood throughout the night, holding onto the hand rails and staring out

to sea and as the sun rose on the smooth glassy sea Dr Weijl and

Liselotte noted that many claimed to see church steeples rising from

the water on the far horizon, a halucination induced by fatigue and

stress.

Harry Hack returned to the engine room where things were now going well and he was able to relax until he suddenly realised that

"...

it was madness to continue on a North-West course any longer. On this

course we would never arrive at the coast of England, and certainly not

at the Thames Estuary where the chances of being picked up would be

better. Back on deck for a captain's council. App. 08.00 Decision to

alter course to West."

He now decided to risk starting the second cylinder,

"The

only problem was that pre-heating would be accompanied by flames and

the sound and fury of the blow lamp. And that may frighten some

passengers! I lit the blow lamp, the glowing plate was hot, fuel

injection engaged, and the stubborn "chook, chook, chook" turned into a

rhythmic "chooka chooka chooka" ...... The engine was running on two

cylinders! Praise be to Kromhout! The boat was gaining speed! A final

adjustment, keep an eye on it for a while, and then back on deck to

enjoy the warm sunshine. Great! But keep listening to the rhythm of the engine."

Karel Dahmen recalled that:

"The response to the helm was slow with only one cylinder firing but at the higher speed achieved with two cylinders working, the response was quite adequate. I sometimes had to turn the helm at short notice to steer around some of the objects spotted by the look outs and did not have a problem with the boat coming around. The problem I did have was that I couldn't easily see the objects with all the people standing in the way and I had to leave the cockpit to get a good look."

Everything

was going well but Harry was conscious of his responsibility and could

not relax for long. He began to worry about the fuel consumption now

that both cylinders were running at at full power. He had assumed that

a lifeboat would always be ready with full tanks but the fuel pipe

disappeared into an inaccessible corner and it was impossible to check

the level:

Without charts navigation was more a matter of guesswork:

"Now

the ship obeyed the helm much better, and it was decided to alter

course to W.S.W. For us, setting the course was a matter of guesswork

and being confident that the chart we had used during geography

lessons, had remained in our memories in the right proportions. We kept

this course up to approximately 15.00 hrs when the course was changed

to S.W. and later to S." (Meijers)

At

about 14.00 according to Hack (but Belinfante gave the time as 15.00

and Meijers as 16.15) "we saw four ships on the horizon":

"After

some deliberation the course was changed towards them, as we could

safely assume that they were not the enemy. They appeared to be paddle

steamers which, under the protection of some destroyers, were probably

mine-sweeping." (Meijers)

"As the lead ship came closer, a cheer went up. She was flying the Union Jack! She was a destroyer: the HMS Venomous - a name meant to strike fear into the enemy but one that to us meant we were safe at last." (Velmans)

"From

the stuff Meyers had found on his survey of the boat I put on an

oilskin, a yellow one, clearly visible. I position myself as

prominently as I can. At the stern we hoist the Dutch 'Red, white and

blue', on the mast the pennant of the Noord-en Zuid-Hollandsche Redding

Maatschappij (N.Z.H.R.M.) with a knot tied in it. 'In sjouw' as the

seaman calls it, which means that we need help.

We receive signals from a signaling lamp. Nothing

unusual for a decent vessel, but far beyond our capability. I can do

nothing better than wave my arms, expressing my helplessness. For some

time nothing happens. It looks as if they do not trust us. I stop the

boat.

Apparently, the destroyer now understands our

situation. A launch is lowered. Talking and fussing. I can't make head

or tail of it. One thing is for certain however: we have made it!!!

(Hack)

HMS Venomous and a sister ship were escorting HMS Sandown and HMS Ryde, two requisitioned Southern Railways paddle steamers which had carried passengers from Portsmouth to

the Isle of Wight but now formed the Dover Flotilla of minesweepers.

The Germans resented them sweeping up their newly laid mines and Venomous was there to prevent their activities being brought to an end by attacking German aircraft. AB Knapton recalled what happened when the Zeemanshoop was sighted:

As they climbed aboard the Dutch harbour tug Atjeh was sighted, with English naval offices standing on its bow. It also came alongside to transfer its passengers, including Cdr Goodenough's "demo" team from Ijmuiden. The story of the Atjeh and its mission to destroy Dutch fuel reserves before they fell into German hands is illustrated with more of Lt Peter Kershaw's photographs.

As the stress ebbed away Harry Hack could only remember fragments of what happened next:

But Loet Velmans (on left), the seventeen year old school boy, remembered that:

"An announcement came over the public address system: the Captain was inviting the crew of the Zeemanshoop

to join him on the bridge. Dick and I tagged along with the four

students, who were the true heroes of the day. The

captain showed us charts of the sea we had just crossed, pointing out

several minefields strung just below the surface of the water. We had

passed right over them, oblivious to the danger. It was only thanks to

our unusually shallow draft that our boat had not been blown to pieces.

He

also told us that our navigation skills left something to be desired.

The North Sea currents had driven us south toward the British Channel.

Had we continued on our course, we would have missed the English coast

altogether and been swept into the Atlantic Ocean, headed for the

American continent. We stared at the captain with a mixture of relief

and utter disbelief."

At first the student crew were asked to take the Zeemanshoop to Ramsgate but "After we told them in a friendly polite manner that we had no idea whatsoever of our position, we were told to also come on board. The Zeemanshoop continued her trip with another crew." (Meijers)

Venomous accelerated to 25 knots and headed for Dover where their passengers disembarked at about 19.00:

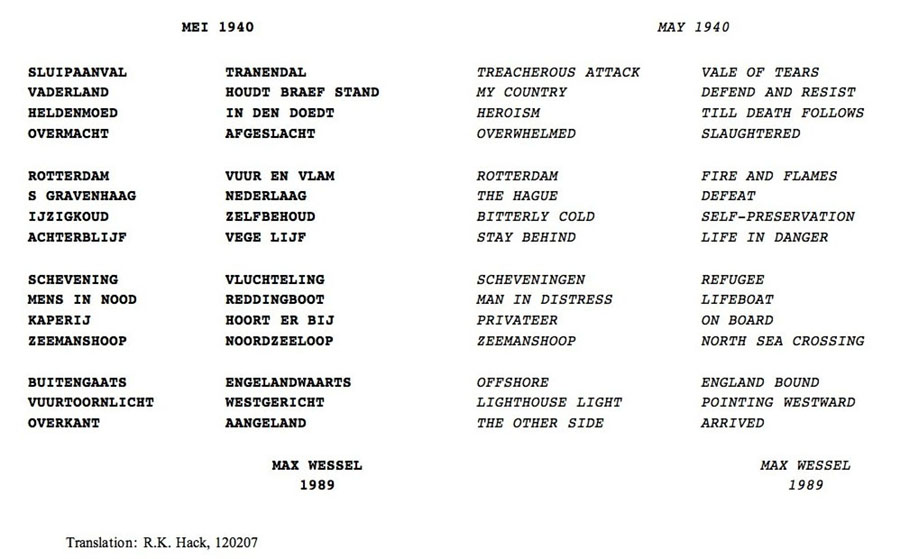

Max Louis Wessel escaped to England on the Zeemanshoop but his parents died in the Holocaust

He wrote this poem in 1989 on the eve of the fiftieth anniversary of the voyage

It has been translated into English by Radboud Hack, the son of Harry Hack

Back home in the Netherlands the following report was published on the 8 June in the Haagsche Courant:

"A significant loss for the fleet of the NZHRM is the disappearance of the rescue boat Zeemanshoop from station Scheveningen. On the evening of 14 May, this boat was captured by armed Dutch military, who saw the chance to start the engine and to sail out (of the harbour) with about 30 refugees on board. Whether the Zeemanshoop reached England (there was fuel for 15 hours) is unknown. Perhaps she was picked up drifting on the sea and brought to a British port. So there is still a slight chance that the NZHRM will recover, after the war, this excellent rescue boat, which has already conducted so many wonderful services in Scheveningen."

Technically, they had "stolen" the Zeemanshoop

but on the day that the Netherlands had surrendered and Germany had

taken over the whole country could that really be considered theft? Lou

Meijers had this to say at the end of his letter describing the voyage:

"I

end this letter offering my apologies for this affair. It was

absolutely illegal, but it saved the lives of many Jewish passengers

and for us was the ideal way out. In case in the future – which Heaven

forbid – our country might surrender again, the N.Z.H.R.M. is on my

list to again lose a lifeboat. As penance I ask you to register me as

contributor."

De

Booy, on paper the Secretary and Treasurer of the Royal Dutch Lifeboat

Association (NZHRM) but in practice the man who really ran it,

concluded his account of the voyage of the Zeemanshoop in Tusschen Mijnen en GrondzeeŽn with the following words:

"After all, the NZHRM did not lose the Zeemanshoop.The

trip of 14-15 May 1940 was one of her most splendid rescues and she was

of use to the Royal Netherlands Navy for five years. All honours to the

four students!"

What happened to the Zeemanshoop after its arrival in England - and where it is now?

Read the story of the Atjeh and Cdr Goodenough's "demo party"

Return to the Home Page of the Zeemanshoop