Dik Speijer and his cousin, Loet Velmans, and their families escaped from the Netherlands aboard the Zeemanshoop on the evening of 14 May 1940. Dik Speijer's account of their escape is a chapter in an unpublished typescript of an autobiography written in 1987. It was sent to me by his daughter and her brother, Bonnie Rosita Speyer-Lively and Terence David Speyer, who also supplied the scans from their father's photograph album.

***************

Our

father was born in Amsterdam February 1922. His parents were Rosette

Cohen-Speijer and David Speijer. He was raised in a middle class,

liberal Jewish environment with very close family ties. Dad’s mother Ro

was one of four sisters and his father David had two brothers and one

sister. Ro was a career woman and David a chemist.

According to Dad’s

journal his grandfather Bram Cohen (father of the four Cohen sisters)

became a partner in a general merchandise store. The business, located

in the heart of Amsterdam, grew beyond all imagination and became the

chain known as The Bijenkorf or Bee Hive. Grandfather Cohen pulled out

as an active partner and sold his portion of the store when the

business became too hectic for his lifestyle. Other relatives and

second generation Cohens stayed in. Ro remained on as a head buyer for

Couture. Dad was raised by nannies with plenty of family members

checking in on him daily.

The four Cohen sisters - from left to right Ro, Jet, Alida, Anna - in 1906

Later known as "De Paarden van Cohen" (the four horses)

Strong - they kept the family together

Ski outing for the four Cohen sisters

From left to right: Alida Cohen-Drukker, Jet (Henriette) Cohen-de Swarte, Ro (Rosette) Cohen-Speyer, Anna Cohen-Velmans

Dad’s

parents divorced in 1933 when he was 11 years old but his father, aunt

and uncles remained a big part of his life. Sadly Dad’s father, aunt

and uncles were all killed in German concentration camps.

The best times for Dad before the war, were

the summers and holidays he spent with his cousins, aunts and uncles

from both sides of the family on the beaches of Scheveningen.

Eventually Ro moved with Dad from Amsterdam to Scheveningen not far

from the city of The Hague. Oma Ro’s sisters Anna and Alida were

already living there with their families. Jet was living with her

family in Zandvoort another beach town not far from Amsterdam.

When living in Scheveningen Dad attended

middle school and eventually he with his cousin Loet went abroad

spending time in England, France, Switzerland and Germany. Dad studied

languages and philosophy.

Then one night in 1939 while in France, Dad received a phone call from his parents to come home immediately. Germany had declared war!

The story of HMS Venomous (D75) is told in A Hard Fought Ship (2017)

I

have never known where the money came from but we were again – this

time in London – royally welcomed and treated. We got clothing, food,

shelter in various hotels surrounding the British Museum and even

pocket money.

Whether this money came from the Dutch

government-in-exile (in London) or from some British government agency,

I have never been able to figure out. But, anyway, we settled down and

times were really not bad at all. On the contrary, Londoners turned out

to be delightful people, helping us when they could and opening up

their homes, we were welcome, wherever we went. I even followed classes

in physics at the London University.

After the first glow of having survived gradually simmered down, living in a hotel, living off charity and having nothing to do but to sit around and wait, became a burden. When the opportunity came to emigrate to America or to the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) we grasped that chance with both hands. I always wanted to go to America, so here, I thought, was my chance.

We went to talk to the Dutch officials who – to my surprise – tried to talk us into going to the Dutch East Indies. And they did a splendid PR job. They painted wonderful pictures of how we would be able to live again in a Dutch environment (Indonesia was, at that time, a colony of the Netherlands), the many business opportunities and they stressed the need for ‘white’ people because the strings with the Dutch motherland were cut off. In addition, we would travel there, going halfway around the world, around the Cape of Good Hope, no less.

We

were talked into it, picked up everything we had and, as so many

Wandering Jews before us, hoped to start all over again in another

country. Six of us went: Loet and his parents and I with mother and

John Blitz. My other uncle and aunt had moved to Wales to work in the

diamond industry which, since the occupation of Holland and Belgium,

had moved there.

In Liverpool, we boarded the SS Viceroy of India,

and started zig zagging the Atlantic Ocean on our way to our first

stop, Gibraltar. (All ships zig zagged at the time to avoid being hit

by German submarines). From there to the Cape Verde Islands. Our

stay there was somewhat scary. The island harbor was shaped in the form

of an ‘8’ with an opening in the bottom and one in the top of the ‘8’,

as entrances to the two-part harbor. While we were in one side, the

German Navy was anchored in the other side of the ‘8’.

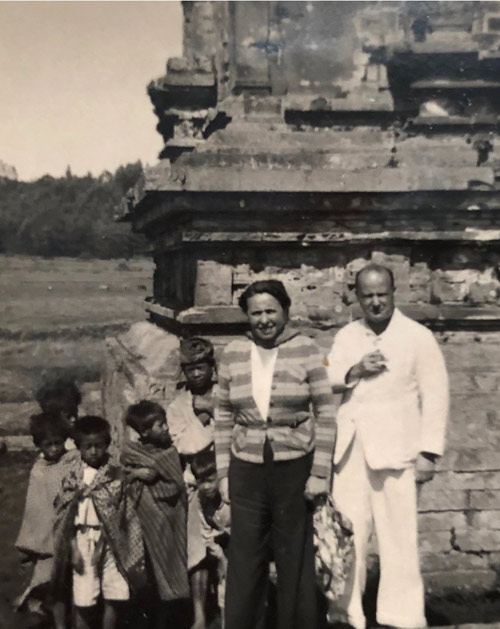

The two Cohen sisters and their families on the SS Viceroy of India traveling from England to the Dutch East Indies.

From left to right: John Blitz, Ro Cohen and Dick Speyer with Anna, Loet and Jo Velmans.

Alida Drukker (nee Cohen) and her husband

Max remained in Wales and Jet de Swarte and Meyer De Swarte stayed in

Holland and died in the Holocaust.

Now,

came a long journey ahead, along the West African coast to Capetown. In

South Africa we took a breather. We traveled the country as tourists

and amused ourselves with the Afrikaans language, which was like

medieval Dutch. (We had to travel around the Cape because the Suez Canal was either closed or too dangerous to use during the war).

Next stop, Mombasa on the East African Coast and on to Colombo, on the Island of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). In Colombo it was so hot and I saw a man digging a hole in the asphalt with the heel of his foot, put a drop of something in it, broke an egg into the hole, fried it and ate it. Beside this experience, I saw there the most beautiful flowers, I had ever seen in my life.

From Colombo to Bombay, in India. For the first time in my life I saw what being poor really meant. I saw beggars without arms or with one leg, beggars full of open wounds on their skin, I saw a dead horse in the middle of the street, covered with millions of flies, I saw women for sale in animal cages, there were narrow streets where the smell was so bad that I had to turn back to the main road ………. yet, on the other side of the Bombay Bay, there were gorgeous condominiums and wealth aplenty. I had never seen such a contrast between the rich and poor, together in such a relatively small area.

I also witnessed a religious funeral ceremony, which made me physically sick, just looking at it. The dead body was put on a rock near the ocean, waiting to be devoured by birds of prey that had been circling over the entire route of the funeral procession. Once the body was put down, they descended on the corps, tore it open and ripped it to pieces. (As I understand it, the religious significance of this ceremony is that the birds would drop their feces over the ocean and that then became the dead person’s final resting place).

Next stop, Kuala Lumpur in Malacca (now Malaysia) and on to Singapore. From there, it was only a short jump to our final destination, Batavia on the island of Java, in the Dutch East Indies.

On board I had met two Jesuit priests. During the entire trip, which lasted, I believe, about two months, the three of us walked the decks every single day. They showed such pleasure to teach me and I couldn’t get enough of their knowledge – and believe me, we were not just talking religion but worldly matters as well. For the rest of my life, although I turned into a religious atheist, I have kept respect and admirations for Jesuit priests. I know that I learned more in those two months than I would have learned in that ‘missed’ fifth grade in high school. It was a sublime lesson in philosophy.

Although

I suspect that the Dutch government-in-exile paid for my trip, I never

found out for sure. What I did find out, however, after arriving in

Batavia, was that the Immigration Inspector, who welcomed us with open

arms, said to me personally: “How wonderful to be able to welcome you

again on Dutch soil and o, yes, you’re 18 years old, I see, you will

have to go into the army.”

THIS, they never told me in London. I got six months to acclimatize.

Our two families moved into a very beautiful and comfortable house and got important, well-paying jobs, right away. We had maids again and the good life had returned where it had left off in Holland.

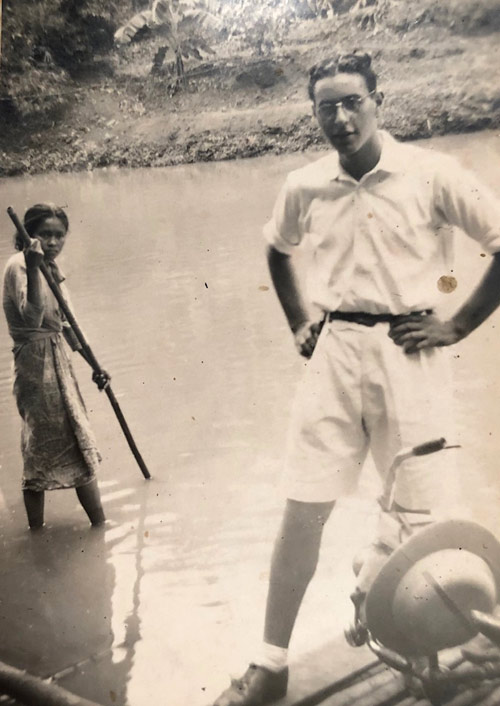

In the Dutch East Indies

Left to right: Loet Velmans with Ro Cohen-Speijer and and her son Dick Speyer

From there they went back to

New York where I was born in 1953. Dad was soon offered another

position at McKee Jungle Gardens in Florida. We moved to Vero Beach

where my brother was born in 1955. I recently found a business

card of my Dad’s: “Dick” S.A. Speyer/ Manager Wild Animal Compound /

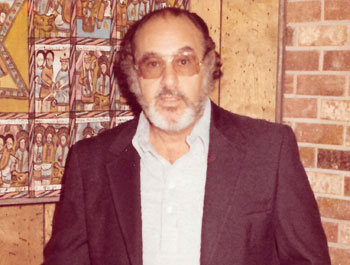

McKee Jungle Gardens. The portrait on the right was taken a Vero Beach in 1980 when he was 58.

From there they went back to

New York where I was born in 1953. Dad was soon offered another

position at McKee Jungle Gardens in Florida. We moved to Vero Beach

where my brother was born in 1955. I recently found a business

card of my Dad’s: “Dick” S.A. Speyer/ Manager Wild Animal Compound /

McKee Jungle Gardens. The portrait on the right was taken a Vero Beach in 1980 when he was 58.