Thomas 'Yorkie' Russell

Stoker on Venomous

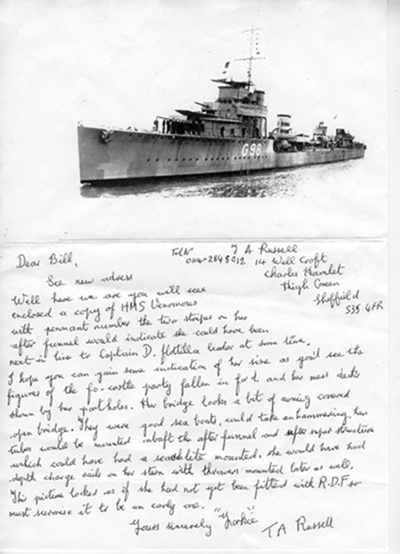

Thomas Arthur Russell was born in 1920 and earned 2/6 a week when he signed up as a a stoker in the Navy for 12 years. He was interviewed by Community Service Volunteers (CSV) Sheffield for the BBC Peoples War website. I was able to trace him and he gave his consent to the use of this material in the second edition of A Hard Fought Ship (2010) and attended the book launch at the Royal Navy Museum in Portsmouth in April 2010. Sadly, these interviews are no longer available on the BBC Peoples War website and I decided to add the description of his time in HMS Venomous to my web site.

In this short passage 'Yorkie' outlined his service in the Navy before he joined Venomous in December 1944:

"My first ship after joining on a 12-year engagement was the battleship HMS Ramillies. I joined her in Alexandria. We operated in offensive sweeps in the Mediterranean and bombarded Fort Cappuso. We had a run in with the Italian Battle Fleet off Cape Spartivento, but could not bring them to a decisive action. I remember being in the forward damage fire and control party, and being near the forward 15” gun barbette on the seamen’s mess deck, we fired a salvo at extreme range. We thought that we had been hit, but it was the concussion of our own main armament, which rolled the ship slightly on to her beam-ends.

I remember the Italian bombers flying at high altitude, being pretty good but not good enough, I remember the old HMS Eagle who carried Gloucester Gladiators Bi-Planes, vanishing behind a wall of spray, raised by these bombers with no damage caused.

We left the Med. and I went on leave for 4 days to Sheffield, just after the Sheffield Blitz, I remember the smoke and steam rising from the bomb damage, streets blown in causing the bus home to go on a round about route.

I served in the North Atlantic on convoy duty, where the German heavy cruiser ‘Hipper’ tried to intercept one of our convoys, she slunk away in the fog before we could bring our main armament to bear. This was in February 1941, well this is just a small part of my service, I served in the Indian Ocean, was torpedoed in the Madagascar campaign, served in destroyers, in operations in the Sicilian and Italian campaigns, loosing many comrades in the mining of HMS Quail. I was in the destructive bombing of Bari Harbour, Eastern Italy when we were unarmed, having been stripped of AA response due to the mining, I was on skeleton crew.

The USS John Harvey carrying mustard gas bombs blew up, so we were exposed to smoke carrying chemicals. Not many know of this, and I can prove it, the harbour next morning was covered in oil with bodies floating in it, some just torsos, a terrible sight, I could tell you so much more.

My war did not really finish in 1945, I went to Norway in May 1945 in HMS Venomous, to take the surrender of the Germans at Kristandsand, I have a scroll from the Norwegian Government, giving thanks for the liberation."

The Venomous was powered by oil burning steam turbines. The engine department of HMS Venomous comprised 14 stokers (including a Petty Officer Stocker and 2nd and 3rd Class stokers) and 6 Engine Room Artificers (ERAs), from 1st to 5th Class ERA. The stokers wore bell bottomed trousers and tunics but the ERA were ‘square rigged’ with jacket, straight trousers and peaked cap. The stokers and ERA had separate mess decks. The Chief Stoker, Charles B Weeks (K.54729) and Thomas Henry Poole (K.62202), had served in Venomous from coming out of Reserve in 1939 to paying off and decommissioning.

The Chief ERA, Arthur 'Wiggy' Bennett, reported to my father Lt(E) William Redvers Forster RNR. The Lt(E) did not take a watch but made unscheduled visits

to the engine room, filed reports on engine performance, etc and kept

the Captain informed of all relevant matters relating to the ship’s

engine.

"After

weeks of waiting back at the barracks, my luck took a turn for the

better and I eagerly scanned the small white slip of paper with my name

on. I had to report to the D.F.D.O. office. I had been put on draft to

HMS Venomous, a destroyer. It was April 1945. It wasn’t a new destroyer like the Quail

but an old V and W class of World War 1 vintage, I believe. Still, it

was a destroyer and it would be a relief to leave the routine of R.N.

Barracks, Devonport.

"After

weeks of waiting back at the barracks, my luck took a turn for the

better and I eagerly scanned the small white slip of paper with my name

on. I had to report to the D.F.D.O. office. I had been put on draft to

HMS Venomous, a destroyer. It was April 1945. It wasn’t a new destroyer like the Quail

but an old V and W class of World War 1 vintage, I believe. Still, it

was a destroyer and it would be a relief to leave the routine of R.N.

Barracks, Devonport.

When I finally arrived at the ship, she

looked ancient. I didn’t realise at the time but she was used mostly as

a target ship for the Barracuda torpedo bombers to practice on. She was

slightly turtle backed and seemed far narrower in the beam. She had two

funnels, one thin, the “woodbine” type and one a bit wider with a

single set of tubes. The stokers’ mess deck seemed smaller than the

Quail’s. You could tell she was aged by the thickness of the paint

below decks, the rivets didn’t stand out as sharply as on a ship of

younger years. Down below, the stokers’ mess deck was far narrower; we

were more crowded together. Her paintwork and overhead corking was

tinged a dirty yellow from the thousands of cigarettes that must have

stained it over the years of service. It smelled of a certain amount of

dampness and paint.

I got to know my messmates over the days

ahead and I found them a great crew. It was April and the days were

often cold and grey. We would go down the Forth to the practice range

and then afterwards, the exercise came alongside. Sometimes, the

torpedoes fired would take some spotting and at times they must have

given our captain a lot of anxiety, for to lose a “fish” entailed the

loss of around a £1000, a large sum in those days. The sea boat’s crew

and the cutters would curse at the time taken to spot the nose of the

torpedo as it bobbed in the troughs, especially if rain had set in.

My war did not really finish in 1945, I went to Norway in May 1945 in HMS Venomous,

to take the surrender of the Germans at Kristansand, I have a scroll

from the Norwegian Government, giving thanks for the liberation.

When we

got ashore on our usual beer laced binges, I found a substitute for my

mother’s bread. As we arrived back outside the naval base, we found

women selling paper bags containing bread rolls, six for a shilling.

The boys went mad for them and if your chums went ashore, you usually

got someone to bring a bag back for you.

I

did manage to get a bit of cod fishing when we anchored off Grantham.

It helped the cook vary the diet. One day we sailed out further than

usual, in fact, we ended up off the most northern tip of Scotland and a

bout of some of the worst weather that I’ve ever experienced. The signs

came as the ship’s company was ordered to secure everything that was

loose and make ready for heavy weather that was imminent. It wasn’t

long coming and it was said to be of hurricane force. The old ship

heaved her fore foot up, rearing up like a startled horse, then came

crashing down her bows, to be buried under an oncoming wave. One whaler

was smashed to matchwood in the davits and I was told that even the

for’d gun shield had been sprained. Items of food and vomit sloshed on

the deck, we had reached the depths of misery. I don’t think we would

have cared if she had sunk. The ship showed her age more, it had made

the rust streaks more obvious, it needed a lot paint and the chipping

hammers would have to work overtime to restore the ship to something of

naval tidiness.

We carried out our usual routine until one

day a buzz originated that we were sailing on some unknown mission;

this was early in May 1945 and we were all eager to know what it was we

were going to do. The Germans surrendered in Europe and some wit said

that we were going to join the Pacific Fleet against Japan. We saw a

uniformed officer who was wearing the regalia of the German Navy. He

was accompanied to the wardroom by one of our officers and the German

was carrying a large briefcase. It eventually transpired that we were

going to Norway and our destination was Kristian Sands, where we were

to accept the surrender of the German forces in Norway. The German

officer had come aboard to act as a pilot through the German

minefields. To make doubly sure, we were accompanied by a couple of

minesweepers.

I felt very uneasy; I remembered the Quail

and the causalities and damage that we had suffered. There was a

crackle of small arm fire and an occasional oerlikon burst. Mines had

been swept and the sweepers were firing at them to sink or to explode

them. I heard no heavy explosions but I did see on one occasion, a mine

coated in red lead bobbing up and down in the choppy sea. This did

nothing for my peace of mind.. Soon I saw another amazing sight; small

craft that I can only describe as smaller than cobbles which used to

take anglers out of the east coast ports. They were Norwegian fishing

boats and I noticed that in them were kids looking about nine or ten

years of age and they were fishing with hand lines.

The Norwegian coast came into view and the

usual talk of getting ashore and wondering what the “Norwegian” parties

would be like. Everyone seemed to be expecting to be swamped by a lot

of busty blondes. It is funny how fantasy can build a picture in one’s

mind of different races and how they should look. We came to anchor in

Kristian Sands; to starboard was a large building that someone said was

a brewery. It was unmarked. Then I saw some hills with German AA

batteries situated on the crest and sides. It would have been sticky if

they thought they wouldn’t surrender after all but I need not have

worried. We were piped ashore leave and my leave would be next day so I

was eager to hear what it was like when the boys came back aboard. Not

one drunk came aboard. Apparently there was a beer of a sort but the

boys said that it tasted like onion water and if you ‘d drunk gallon,

you couldn’t get drunk.

I did get ashore eventually after we had

tied up alongside a sweeper. I got a surprise when the bosom’s mate

shouted down the mess deck hatch, “Anyone here by the name of Bill

Russell?” A chorus of voices shouted, “There’s a stoker called Tommy

Russell, maybe its him.” “Well tell him there’s a stoker, Tony Harding

off the sweeper here.” What a surprise, Tony is the wife’s brother. I

knew that he had joined the navy as an H.O. but never knew he was on

the sweeper alongside; my wife must have told him that I was aboard the

Venomous. I went aboard the sweeper and sampled his tot and wished him

well. They had swept the mines up and had been firing at them, and here

he was now. I’d have to write home to Magdalena; she would be surprised

that her husband and her brother had met like that. In a way he was

helping to keep me safe; such is fate.

I got ashore next day and wasn’t impressed

at all. The people seemed few and far between and not so talkative

either. They seemed in a state of shock, as they couldn’t believe that

they had been liberated. Then to be fair, they had never had the chance

of seeing many of the goods in the shops that even we in rationed

Britain had seen. The kids had never seen chocolate and I expect fruit

like oranges and bananas either.

What

struck me was a squad of German sailors marching past, still armed and

we had not so much as a knife between us. Maybe they were happy that

the war was over, maybe they were having a little joke at our expense.

We went back aboard early, an hour or two was long enough in that

lifeless place. While there, I suffered a bit of embarrassment. My pal

and I decided to have a bath down in the narrow washroom situated just

below the mess deck. This compartment had only one hatch into it and

you had to bath in a large round bowl. There were only two of these

bowls and you didn’t always have enough hot water anyway to fill the

two.

This day we were in luck; we took our

washing down and with it, the usual bar of pusser’s soap and a knife to

shave some onto the washing. I had got one of the metal tubs and as I

was filling it, I decided to kill two birds with one stone and I would

wash my clothes and bathe in the same water; my mate decided that it

was a good idea. There we were both in the nude, perched with our

buttocks on the edge of our respective tubs, rubbing our washing in the

lather the soap shavings had created. My back was towards the washroom

entrance and I was concentrating on the job in hand. Suddenly, I heard

a clattering of feet on the hatchway’s steel ladder, nothing wrong with

that but then I heard the unmistakeable sound of female laughter. “Cor

Yorkie,” my mate said, “Look behind you.” I turned and it must have

been one of the few times that a sailor has blushed. There, laughing

and pointing, were several Norwegian girls; what do you do in such a

situation? We just carried on with our washing. I’d never felt so

embarrassed. The b******s on the mess deck had actually directed the

girls down to the bathroom and had had a good laugh at our expense. The

girls had been invited aboard on a good will trip; they certainly had

something to tell their folks. The boys on the mess deck, said, “Did

you give them a flash, Yorkie?” But as luck had it, my back was towards

them.

This day we were in luck; we took our

washing down and with it, the usual bar of pusser’s soap and a knife to

shave some onto the washing. I had got one of the metal tubs and as I

was filling it, I decided to kill two birds with one stone and I would

wash my clothes and bathe in the same water; my mate decided that it

was a good idea. There we were both in the nude, perched with our

buttocks on the edge of our respective tubs, rubbing our washing in the

lather the soap shavings had created. My back was towards the washroom

entrance and I was concentrating on the job in hand. Suddenly, I heard

a clattering of feet on the hatchway’s steel ladder, nothing wrong with

that but then I heard the unmistakeable sound of female laughter. “Cor

Yorkie,” my mate said, “Look behind you.” I turned and it must have

been one of the few times that a sailor has blushed. There, laughing

and pointing, were several Norwegian girls; what do you do in such a

situation? We just carried on with our washing. I’d never felt so

embarrassed. The b******s on the mess deck had actually directed the

girls down to the bathroom and had had a good laugh at our expense. The

girls had been invited aboard on a good will trip; they certainly had

something to tell their folks. The boys on the mess deck, said, “Did

you give them a flash, Yorkie?” But as luck had it, my back was towards

them.

One day as some of the boys were returning

aboard, they came across a stranger in a uniform that they had never

seen before. He wasn’t German and he had only a very slight knowledge

of English. He managed to get across that he was very hungry, doing

this mostly by sign, pointing to his mouth and to his stomach. His

uniform was a green shade, nearly the so-called Lincoln green of Robin

Hood. He was escorted off the dockside, down to the mess deck and was

seated while someone went off and brewed the mess deck tea urn to the

half way mark. A large tin of baked beans was opened and half a large

loaf was cut up into thick slices and liberally coated with butter.

This repast was placed in front of him as he literally drooled at the

sight. I think he would have kissed us all if we had let him. His

thanks were embarrassing; I’d never seen anyone starving like this man.

He wolfed the food down and we just sat and watched him. His words were

Russian sounding and he did claim that he was a Russian prisoner of the

Germans and said that the Germans had shot some of his mates before we

arrived. We made sure that he had his fill and then we packed him off

before any officers arrived on the scene and kicked a stink up. We had

after all, managed to get him aboard unbeknown to the officer of the

day. I often wonder about this man and his eventual fate, for since the

war, we have heard reports that the Soviets didn’t treat returned

prisoners of war very well, saying that they should have fought to the

death and they looked on the prisoners as traitors.

After this, we sailed soon for Grangemouth,

Scotland where we expected a shore leave would bring us a chance of

some celebrating and maybe a pint or two of free beer. We need not have

bothered. You might have thought that the war was still on. I reckon we

could have been in a better place than this. The Scottish seemed to be

tight fisted as was often said. Still, the war in Europe was over now

and everyone hoped that the Pacific war with Japan wouldn’t be long. I

stayed with Venomous a few

more months, just the usual exercises with the Fleet Air Arm and a few

training patrols. I returned to barracks on July 7th and I got seven

days’ leave granted. I was in heaven back with my wife and daughter

again looking as beautiful as ever.