Eric Pountney, Telegraphist, and George Speechley, Signalman, both joined HMS Venomous

at Rosyth on the 31 July, the same day as its first wartime CO, Lt Cdr

Donald MacIntryre RN. Poultney must have used a tripod to

photograph himself in the W/T Office on Venomous and his fellow telegraphists off duty in the dim light of their Mess deck. He kept copies of signals received or sent during the evacuation of

the Welsh and Irish Guards from Boulogne on the 23 May 1940, one of the

most dramatic events described in A Hard Fought Ship, and during the first of five trips to evacuate the troops from the North Mole and beaches near Dunkirk

on the 31 May. They record events as they happened while the outcome

was still in doubt. You can link to these signals from the foot of this

page.

But

before the signals tell their story I have asked a Wireless

Telegraphist on a wartime destroyer to describe the use of telegraphy

and visual

signalling. Keith Burns (on right below) was nineteen when he joined the modern U Class destroyer, HMS Undaunted,

at Malta in September 1944 as a Wireless Telegraphy Operator. Its

Commanding Officer, Lt Cdr Angus A. Mackenzie RNR, had been "No 1" to

Lt Cdr John McBeath RN, the CO of HMS Venomous

at Boulogne and Dunkirk in 1940.

Keith

described to me in a series of

e-mails the work of the telegraphists aboard a wartime destroyer and

gave me a better understanding of the photographs and naval signals

brought home from the war by Eric Pountney.

"It

took five months to train a Wireless Telegraphy Operator. They began by

learning Morse code and the navy's methods of sending and receiving

signals. To pass out at the end of the course they had to be able to

read at twenty-two words per minute and transmit at ten words per

minute. Telegraphists were also trained in coding since there were very few coders at the beginning of the war.

"It

took five months to train a Wireless Telegraphy Operator. They began by

learning Morse code and the navy's methods of sending and receiving

signals. To pass out at the end of the course they had to be able to

read at twenty-two words per minute and transmit at ten words per

minute. Telegraphists were also trained in coding since there were very few coders at the beginning of the war.

Once

completing training one became an Ordinary Telegraphist and advanced to

Telegraphist and Telegraphist (Trained Operator). Some ships had a

Leading Telegraphist and all destroyers would have a Petty Officer

Telegraphist. Flotilla Leaders would have a Chief Petty Officer.

Rates

were distinguished by the badge on their right arm. All Telegraphists

wore a badge with wings crossed by streak of lightning representing a

radio frequency pulse. Telegraphists (Trained Operators) wore

the same wing but above it was a star. Leading Telegraphists (W/T3)

wore the

wing with one star above and one star below and like all other Leading ratings, were entitled to wear an anchor, known as a 'killick', on the other

sleeve. This was known as 'Having picked up the hook'. The badges

(similar to an army corporal's 'stripes') on the left arm beneath the killick

were awarded

for good conduct., one after three years service, two after seven years

and three after twelve years. Keith

Burns was a Leading Telegraphist with one badge below the hook

(killick) on his left sleeve when this photograph was taken. A Petty

Officer Tel. would have a

crown above the wings and crossed anchors on the other arm (on left). The Chief

Petty Officer Telegraphist wore the wings on each collar of his jacket,

with a crown above, and a single star below but only after having had

the rate for a year.

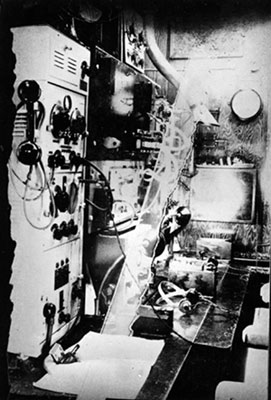

The bulk of the signals were at relatively long range. Radio Silence was usually essential so they mainly came from shore bases. We sat in the W/T Office in front of a receiver and wore headphones while we read all the signals that were transmitted to ships in the part of the world in which we were operating. Separate sets were used for transmitting and receiving, the latter being smaller. Some of the signals were for the attention of all ships in that region and others for particular ship(s). The equipment in the photograph of photograph of the W/T Office on Venomous is very different from that on HMS Undaunted.

The signal had to be framed in a certain way beginning,

obviously, with the address. The address would be in letters and the

text in groups of four figures. Every

signal, even if it were for the same ship, would have a different

address and it would only become clear as to who it was for when the

address had been decoded. Ten signals, ten different addresses due to

the coding. I know it sounds double dutch but it was the sophistication of the coding.

The signal had to be framed in a certain way beginning,

obviously, with the address. The address would be in letters and the

text in groups of four figures. Every

signal, even if it were for the same ship, would have a different

address and it would only become clear as to who it was for when the

address had been decoded. Ten signals, ten different addresses due to

the coding. I know it sounds double dutch but it was the sophistication of the coding.

When the

address had been received and written on a message pad, we would let

the coder on watch see this and he would decode the address to see if

it concerned us. The key to the

code were the two identical five figure groups at the beginning and end

of the signal. I have always considered that it must have been

impossible to break the code but I don't know if the enemy ever managed

it. The coder would either decode the text

himself or if the security was above a certain level pass it to the

ship's Signals Officer for decoding.

All ships carried a Signals Officer and on destroyers this was often

the ship's Navigating Officer.

Petty Officer Telegraphists

sometimes insisted that the telegraphist reading the signal should read

it all even if we had no interest in it. This was seen as good practice

in developing one's skills.

These transmissions went on 24 hours each day and in the rare cases of

there being nothing to send, then the transmitter would repeat signals

sent earlier. These signals were known as "Routines" and it was usually

the job of the more junior ratings to read these. As a result they were

reading constantly during their watch. No let up. There were times when

signals were impossible to read due to atmospherics or other

conditions. Signals were consecutively numbered so we knew if something

had been missed. Some telegraphists were better at tuning a receiver

than others, a constant frustration. Unless engaged with the enemy radio

silence was essential to avoid giving away the position of the ship and for close range communication the visual signalman came into their own.

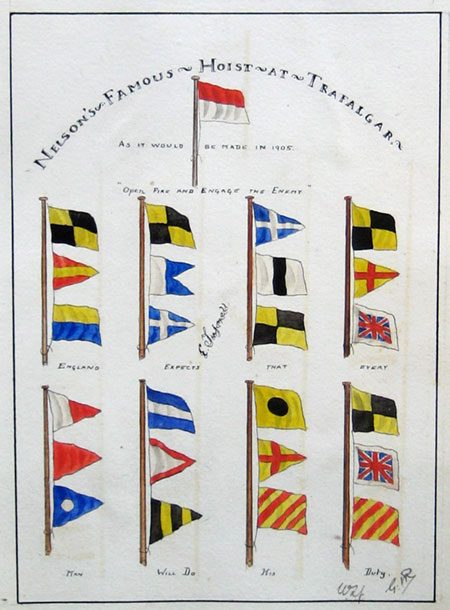

In 1905 Midshipman Eric E.C. Tufnell painted "Nelson's

Famous Hoist at Trafalgar" in his Midshipman's Log but at the Battle of Jutland signal flags

had been obscured by smoke from the funnels of the battleships.

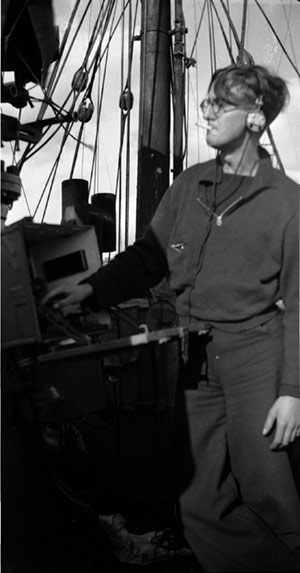

"Bunting tossers" (Visual Signalmen) increasingly communicated with

other ships in company with flashing lights (in morse

but plain language, not coded). There were 20 inch and 10 inch

signalling lamps and smaller

hand held Aldis lamps. In clear weather the 20 inch lamp could

be read quite easily at 10 miles distance but lamps could only be used in

daylight.

After dark they would have been a security risk. Oscar Maylands is the man using the large lamp in the photograph. Flags were still used

for passing signals at close range but their use diminished as Radio

Telegraphy (for voice transmission) became more popular, particularly

amongst the huge fleet operating in the

Pacific. The same equipment was used for receiving and transmitting,

unlike W/T.

In 1905 Midshipman Eric E.C. Tufnell painted "Nelson's

Famous Hoist at Trafalgar" in his Midshipman's Log but at the Battle of Jutland signal flags

had been obscured by smoke from the funnels of the battleships.

"Bunting tossers" (Visual Signalmen) increasingly communicated with

other ships in company with flashing lights (in morse

but plain language, not coded). There were 20 inch and 10 inch

signalling lamps and smaller

hand held Aldis lamps. In clear weather the 20 inch lamp could

be read quite easily at 10 miles distance but lamps could only be used in

daylight.

After dark they would have been a security risk. Oscar Maylands is the man using the large lamp in the photograph. Flags were still used

for passing signals at close range but their use diminished as Radio

Telegraphy (for voice transmission) became more popular, particularly

amongst the huge fleet operating in the

Pacific. The same equipment was used for receiving and transmitting,

unlike W/T.

We had eleven telegraphists and two coders on HMS Undaunted

and I think that was fairly typical for destroyers. On our Mess we had

telegraphists, visual signalmen and coders but no RDF operators (they

were classed as seamen). Hammocks

were slung over the mess table but only after a certain time in the

evening. The long seat on which we sat at the table had a top which

could be lifted up and covered our lockers. The seat was topped with a

cushion and some ratings slept on this instead of slinging their

hammocks. One of the most popular places was on the table itself where

the person would lay his hammock.

Two telegraphists would be on watch together

in the W/T Office and there were, of course, four watches. I was interested to see the photo taken in the W/T Office on Venomous

and it looks as if it was even more cramped than ours. I did not

recognise any of the wireless sets. I guess they had all been

superceeded by my time.

HMS Venomous was an elderly V&W Class destroyer built in 1919 and HMS Undaunted

was a modern newly built U Class destroyer. The equipment we used was

more advanced than that installed in HMS Venomous

when Eric Pountney (photographed below) joined it in August 1939.

Bill Legg, Curator of the Royal Navy Museum of Radar and

Communication describes the equipment used on Venomous at the bottom of

this page.

Procedures may also have changed

between1939 when Eric Pountney joined Venomous and 1944 when I joined Undaunted.

I think the signals he kept are copies, not originals, as they differ

from the standard practice for recording the Time of

Origin (TOO) in 1944. The time which we put on a

signal comprised the first two figures for the date and the next four

figures for the time (the month was not recorded) and then a letter which represented the time zone.

By the time I joined Undaunted there was one transmitting station (Whitehall) for the whole of the

Home and Atlantic Fleets, one for the Mediterranean Fleet, and a very

few others but surprisingly only one (Hawaii - Pearl Harbour) for the

entire Pacific.

The

Americans made their routine signals by machine which transmitted at

about 30 words per minute and when reading these it was totally

impossible to write quickly enough. All American telegraphists

(Radiomen) were trained to type so that when receiving speeds at this

rate they could type instead of writing. When the British Pacific Fleet

(BPF) was formed and we arrived in the Pacific, all our telegraphists had to

be trained in typing.

The Royal Navy was embarrassed that it could neither send of receive

Morse Code at the speed of the USN, which, months later, after VJ day

in August 1945, led to a complete rethink on training RN Telegraphists.

Towards

the end of the war Radio Telephone (R/T) came to be used between ships

in company and uncoded voice messages were transmitted. This was a

tremendous advantage to the fleet in company. It also relieved the

Signalmen of a lot of work much to the disgust of the telegraphists!

There were many ancillary matters covered by telegraphists such as the

technical aspects of the equipment, batteries etc.

A few telegraphists were trained as High

Frequency/Direction Finders (HF/DF, known as "huff-duff") to determine

the position of German U-boats and commerce raiders, but they only had

to carry out

these duties at specific times. At other times they had the normal

duties of "sparkers" which lightened the load on the mainstream telegraphists and we could switch to four watches instead of three.

I would like to finish by telling you a personal story. I was on watch in the W/T office during the middle of the night. Things were fairly quiet and I had turned the volume on my receiver to its highest level and then hung my headphones around my neck. Of course I fell asleep. Asleep on watch - was there a worse crime? Who should come into the office but our Signals Officer. Did he put me on a serious charge? No. He put his hand on my shoulder, I awoke and he said, 'Burns, one day someone will catch you asleep on watch.' Then without another word he walked out and the event was never mentioned again. I made sure it never reoccured and the officer's behaviour was a lesson to me in humanity which I was able to use in my own career, with my own staff. I told him this after the war."

Radio Telegraphy equipment on HMS Venomous

Bill Legg, the former Curator of The Royal Navy's Museum of Radar and Communication at Fareham, describes the equipment for receiving and transmitting telegraphy on HMS Venomous when Eric Pountney joined in August 1939 and later modifications:

"Venomous

went to war with archaic equipment installed in the late 1920s but was

still able to communicate with the shore and other Fleet Units at sea.

Visitors to the Royal Navy Museum of Radar and Communications can see a mockup of a 1920 period W/T Office. The receiver consisted of up to six separate parts, each bulkhead

mounted and interconnected. The transmitter, was similar but had fewer units married together. Venomous had

two quite separate areas devoted to wireless telegraphy, the

main operating area containing the receiver and associated equipment

and another for the high powered transmitter.

The Type 37S transmitter had been introduced in 1924 and last modified in 1930. The

"SPARK" waveform of the Type 37S was extremely dangerous

and unpredictable and in the past operators had received fatal electric

shocks and RF burns. The operator sat well away from the transmitter in

a 'cage' which in a small ship like Venomous was an integral part of the W/T office. The high powered transmitter was connected to the aerial on the

superstructure via metal trunkings which ran through the decks of the

ship, and this trunkings radiated dangerous RF voltages resulting in

very little of the power actually getting to the aerial - such were the

losses. Touching that trunking, or being thrown onto the trunking in

rough weather, was not recommended.

In

1942 following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbour and Germany's

declaration of war on America the US stepped up its assistance to

Britain, including the supply of modern radio communication equipment

to the Royal Navy. HMS Venomous may have been equipped with the new US supplied Type 60 transmitter or

one of its variants during its major refit in the first quarter of 1942

after its collision with HMS Keppel.

This transmitter was kept quite separate from the

receiver in the W/T Office and wired with coaxial cable direct to a

transformer which was directly connected/coupled to the intended

aerial. Thus, all the intended output power went into the ether and

personal shocks became a thing of the past. HMS Undaunted would have been fitted with the Type 60 transmitter when built."

From Morse Code to Modern Data Transmission

Morse Code required expert operators to intrepret the signals into

alpanumeric characters but eventually machines were developed which

de-skilled the task by allowing characters to be typed and printed

which could be used by low paid operators. Electro-mechanical machines

were replaced in the 1970's with computers, the 5 bit Baudot Code grew

into 7 bit ASCII code allowing 128 characters to be coded. Today ASCII

is replaced by Unicode, a 32 bit code which can encode every

characterof every language of the world, but the basic principles of

the modern Internet age are still those of Wheatstone and Morse. Wth

due acknowledgement to "Telegraphy: a brief history" by Trevor L Cass.

I shall end this page with another of Keith Burns' stories:

Eric Pountney kept copies of the naval signals received and sent by HMS Venomous during the evacuation of the Welsh and Irish Guards from Boulogne on the 23 May 1940 and on the 31 May when Venomous

made the first of five trips to evacuate the troops from Dunkirk. There

was no need to preserve radio silence as the destroyers were in close

contact with the enemy and their positions were known. Most of the

signals are from ship to shore where, Bertram Ramsay, Vice Admiral

Destroyers (VAD) was directing operations from Dover Castle. These

signals give a vivid impression of decisions being

made and sometimes reversed in response to rapidly changing events.

Follow events as they happened by reading the naval signals received and sent by HMS Venomous at

Boulogne on the 23 May 1940 and Dunkirk on the 31 May 1940

Eric Pountney was a keen photographer and his pictures tell the story of his wartime service