Otto Neurath and and Marie Reidemeister

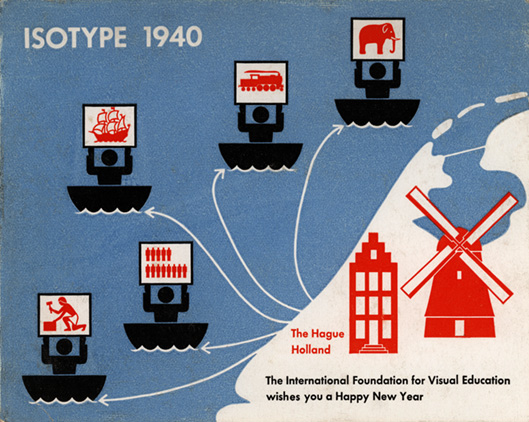

Otto Neurath and Marie Reidemeister had arrived in The Hague

from Vienna after the Austrian fascists took over the city in 1934. In

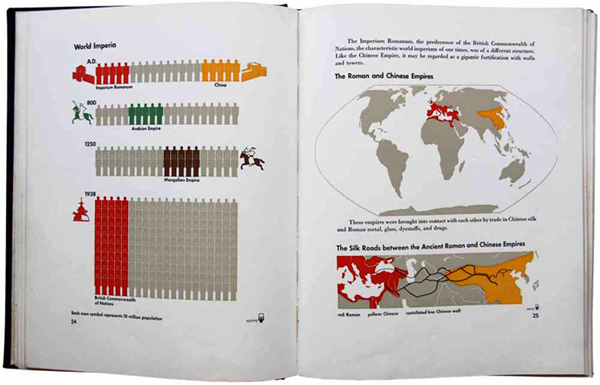

Vienna they had pioneered the use of symbols and icons to communicate

statistical and factual information in exhibitions and for adult

education. In the Netherlands they had established the International

Foundation for Visual Education and renamed their Vienna method Isotype

(International System of TYpographical Picture Education). When the

invasion of Holland began in May 1940, they hid in their apartment,

depending on Dutch friends to deliver food. When Dutch surrender seemed

likely they had escaped to the harbour at Scheveningen.

A

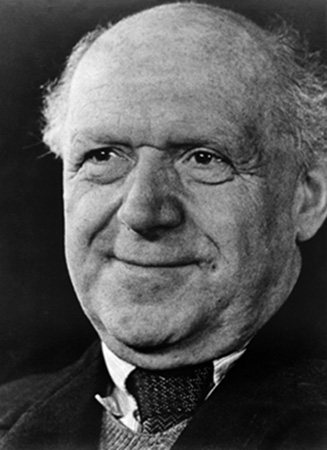

characteristic portrait of Otto Neurath (left) and the New Years

greeting card of the International Foundation for Visual Education, 1940

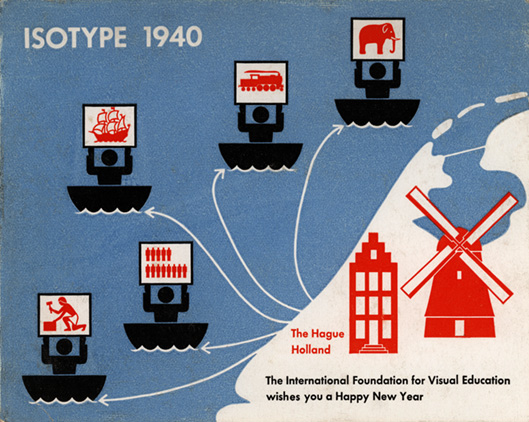

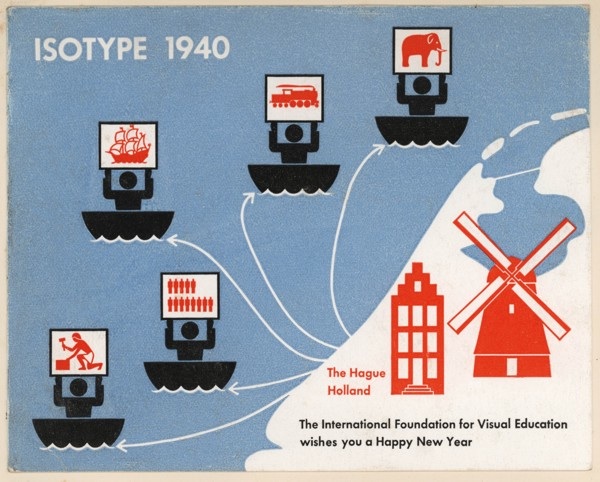

A

characteristic portrait of Otto Neurath (left) and the New Years

greeting card of the International Foundation for Visual Education, 1940

Courtesy of the Otto & Marie Neurath Isotype Collection, University of Reading

At first, all they could see were the fishing boats and fishermen

standing around, smoking pipes. There were soldiers on the beach. An

oil depot was on fire and the air was black with smoke. British and

Dutch troops had been destroying fuel reserves along the coast to

prevent the Germans using them. Otto said, “If we don’t find a boat I’m

going on a piece of wood”

But they found the

Zeemanshoop.

In charge of the boat was a student called Harry Hack, “a fine name”,

remarked Otto, “for such an adventure”. More than forty people had

already gathered on board when they arrived. Otto joked that when they

jumped from the high dock, they jumped “head over heels”. Marie said

that his weight nearly sank the little boat. They thought they were the last to join

the already overloaded boat. A Dutch soldier shot his gun into the air

to prevent any more refugees from boarding. By the time they set off it

was evening.

Marie later wrote about the journey on the

Zeemanshoop

“For us this was a great adventure indeed. We were immersed in the

stories of the Huguenots and their flights in fog and night over the

frontiers and the sea - so there we are, we know how it feels”. She and

Otto were glad to be alive and “extremely happy” to have found the

“tiny nutshell of a boat”. Neurath described their rescue by HMS

Venomous, and how they were given “bananas, tea and kindness”.

On arrival in Britain both Otto and Marie were classified as "Enemy

Aliens". On the 11th May, in response to German campaigns in Europe,

the British military had persuaded the Home Secretary Sir John

Anderson, “that every male enemy alien between sixteen and seventy

should be removed forthwith from the coastal strip.” This strip

stretched from the Dorset coast right up to Inverness.

The May “coastal strip” ruling meant that the majority of newly arrived

refugees from Europe, mostly Jews, were among the three thousand people

interned. Otto and Marie were separated and taken into custody as they

landed at Dover. Neurath explained to the British police that he was

the author of the book

Modern Man in the Making.

To prove it, he pulled from his pocket a review of the book illustrated

with a photograph of him. This review was one of very few documents and

papers he had brought from the Hague. Neurath later wrote that,

“the bobbies did know Modern Man in the Making, and did hardly believe that the author was with them. Fortunately I had with me a review of my book with a photo of mine”.

If they were pulling his leg, Neurath, with his limited English, did not realise it.

Otto and Marie are among the notable internees mentioned in François Lafitte’s book

The Internment of Aliens,

which was published in late 1940 while the internment policy was still

in place. Otto Neurath is described as “world-famous pioneer of

pictorial statistics” who “fled from Vienna in 1934 because he was a

Social Democrat”. Marie is not mentioned by name but as Neurath’s

“chief statistical assistant to whom he is engaged”. In fact she was

known as a “transformer” – a role that mediated between researchers and

artists, combining artistic and design ability with understanding of

educational theory, statistics and science.

Lafitte’s description of Otto is accurate but hardly touches on his

achievements. Neurath was in fact a polymath, well-versed in economics,

science and philosophy. In Vienna he had established extraordinarily

innovative museums and travelling exhibitions which were amongst the

first to use artificial lighting, interactivity and hands-on exhibits,

night-time opening and film screenings. He also co-founded and named

the influential Vienna Circle, whose philosophy of “logical positivism”

was world-famous.

It was Marie who alerted British friends that she and Otto were in the

country. She was able to do this because while the German and Austrian

men from the

Zeemanshoop were immediately arrested, the women were not.

The refugees were transported from Dover to Victoria station. Marie was

taken to the Fulham Institute for the night, a place she described as a

Dickensian poorhouse. The next day she was taken to Holloway. Neurath

was imprisoned in Pentonville. He wrote, “I studied Pentonville, a

famous prison (spies are hanged there)”.

From Pentonville, Neurath went to a makeshift camp at Kempton Park

Racecourse. There the internees were housed in the racecourse

buildings, in stables, and in tents. They slept on mattresses on stone

floors, up to a hundred men to a room. Nearly a month after his arrival

in England, Neurath was shipped to the Isle of Man. He was among the

men taken on two ships, the steam packet

Rushen Castle and the smaller

Victoria, between the 11th and the 14th of June. The

journey from Kempton Park to Douglas on the Isle of Man took seventeen

hours.

Neurath was imprisoned in

Onchan camp (pronounced Onken), in the

village of Onchan, at the top of Douglas bay. The second world war

internment camps on the Isle of Man were made from the streets in the

towns of Douglas, Ramsey and Port Erin, and the Victorian boarding

houses were requisitioned.

At first, the camp authorities disallowed access to radio and press:

the men built their own radios. Soon they realized that the internees

posed little threat, and the ban on communications was lifted. Inside

the camp a newspaper was published by the internees: the

Onchan

Pioneer. A “Popular University” was quickly established, and between

May 1940 and February 1941, four hundred and ninety-six lectures were

held. At least one of these was given by Otto Neurath. According to the

Onchan Pioneer Neurath’s lecture held the record of the highest

attendance for an indoor lecture. Two hundred and fifty men came to

hear him give a lecture in sociology cryptically titled ““How do you

make the tennis court so durable?”.

Marie’s experience of internment is better documented than Neurath’s –

she was interviewed for a book on the internment of women. From other

refugee accounts, we know that the emotional impact of internment was

very varied. For some prisoners it was traumatic, particularly for

those who had already experienced the Nazi concentration camps. Both

Marie and Otto took it remarkably well. Separation from one another was

painful, though they told the authorities that they were married, and

so were able to meet after a few months (Marie was in a women’s camp in

a different town on the island). In letters written after his release,

Neurath insisted it was not a terrible experience for him. He wrote:

“I was more interested in the sociological facts, therefore less

disturbed than some others of my mates. Mary was of the same mood. Both

of us regarded the first weeks in prison etc. as a kind of relaxation

or holidays after the tension in Holland”.

They were released in early February 1941 after appeals from famous

figures such as Julian Huxley and Albert Einstein and immediately

married. Marie became

Neurath’s third wife: his first wife was

Anna Schapire-Neurath

(1877-1911). With Anna he translated the Eugenicist Francis Galton’s

Genius and Heredity into German, and had one child, Paul Neurath.

Neurath’s second wife,

Olga Hahn (1882-1937) was a highly gifted

mathematician, who had become blind in her early twenties. Olga died in

The Hague, from complications following an operation.

Otto and Marie Neurath (on right, courtesy of the Otto and Marie

Neurath Isotype Collection) immediately set about establishing a new

Isotype

Institute in Oxford. The principal artist of Isotype, Gerd Arntz, had

stayed in the Netherlands. Without their team, and especially without

the graphic talent of Arntz, rebuilding their work in England was

difficult. Even so, the Institute became influential in propaganda,

adult education, town planning, film and information design during the

early 1940s. They made films for the Ministry of Information, worked

with the renowned documentary filmmaker Paul Rotha, and produced

statistical charts to illustrate numerous books. They made charts for

international organizations, and involved themselves in political

groups including the Fabians and the China Campaign. Neurath was

involved in early plans for Britain’s post-war reconstruction, but died

suddenly in December 1945.

Neurath was fifty eight years old when he arrived in Britain. Marie was

forty two. She was attractive, quietly intelligent, and tended to

underplay her own role in the work they did together. She spoke

excellent English, while Neurath joked that he spoke “broken English

fluently”. He was a very compelling character: unusually big for his

generation (in height and girth) with a loud voice. The philosopher

Karl Popper described him as ““a big, tall, exuberant man with flashing

eyes … The impression was of a most unusual personality, of a man of

tremendous vitality and drive.”

Otto Neurath died suddenly in 1945, possibly from a stroke. He had

enjoyed living in Britain and appreciated the “British muddle” and also

the British lack of respect for “genius”. At the time of his

death he was writing about tolerance and brotherhood, and the

re-education of young Germans and Austrians who had been indoctrinated

under the Nazis.

He and Marie were also busy helping the town council of Bilston, near

Wolverhampton, plan their post-war reconstruction. The Town Clerk A.V.

Williams, later remembered that he “made one believe in the dignity of

human beings” and that “the pursuit of beauty and happiness could be

achieved by the common man”.

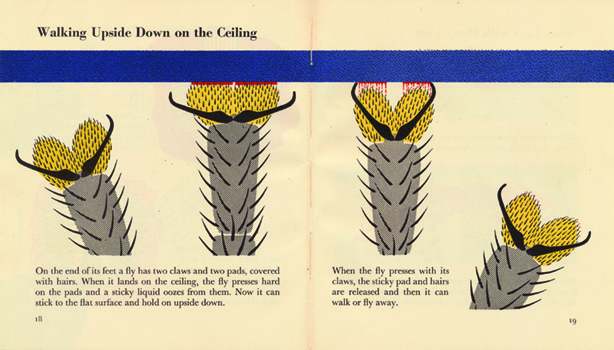

Marie Neurath continued living and working in Britain. She died in

London in 1986. She had taken Isotype in a new and influential

direction in her beautifully designed and educational children’s books.

They were designed on the basis of a deep understanding of how children

conceptualise the world, and today are highly collectible. Many people

who grew up in Britain between the 1950s and the 1970s, would recognize

these books from their own childhood.

Michelle Henning

Senior Lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies

University of the West of England

Marie’s experience of internment is better documented than Neurath’s –

she was interviewed for a book on the internment of women. From other

refugee accounts, we know that the emotional impact of internment was

very varied. For some prisoners it was traumatic, particularly for

those who had already experienced the Nazi concentration camps. Both

Marie and Otto took it remarkably well. Separation from one another was

painful, though they told the authorities that they were married, and

so were able to meet after a few months (Marie was in a women’s camp in

a different town on the island). In letters written after his release,

Neurath insisted it was not a terrible experience for him. He wrote:

Marie’s experience of internment is better documented than Neurath’s –

she was interviewed for a book on the internment of women. From other

refugee accounts, we know that the emotional impact of internment was

very varied. For some prisoners it was traumatic, particularly for

those who had already experienced the Nazi concentration camps. Both

Marie and Otto took it remarkably well. Separation from one another was

painful, though they told the authorities that they were married, and

so were able to meet after a few months (Marie was in a women’s camp in

a different town on the island). In letters written after his release,

Neurath insisted it was not a terrible experience for him. He wrote: