Donald

Macintyre known to his fellow officers as D. Mac was one of the most

successful wartime COs of convoy escorts in the Battle of the Atlantic

credited with sinking at least seven U-boats, including U-99 commanded

by Otto Kretschmer, the most successful U-boat commander of them all.

His autobiography, U-Boat Killer,

is perhaps the best account of the war against the U-boats by a serving

officer. He went on to write many more books on the Battle of the

Atlantic.

Donald George

Frederick Wyville Macintyre was born at Dehra Dun, the son of a major

general in the Indian Army, on the 26 January 1904. He attended a

preparatory school in Cheltenham and the Royal Navy College Osborne

before joining the Royal Navy as a fourteen year old cadet at Dartmouth

in 1917.

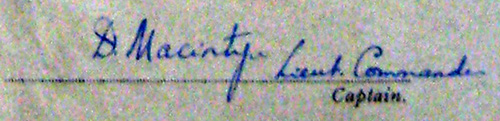

The following extract from his autobiography describes his time as CO of HMS Venomous from joining his ship at Rosyth on the 31 July 1939 to handing over to Lt Cdr John E.H. MacBeath RN on the 8 January 1940. The photograph of him on the open bridge of a V&W Class destroyer was probably taken on HMS Walker.

****************

"In 1937 I graduated to my first destroyer, the Defender, on the China station. With her 35,000 HP and 32 knots, she was a very different proposition from my little 785-ton Kingfisher

and her 20 knots. I thanked my stars for my early destroyer training in

the old Mediterranean days as the flotilla streaked about the China

Sea, performing its intricate manoeuvres at 30 knots. But this soon

came to an end with the beginning of the war between Japan and China,

when every ship on the station was required to bring comfort and

confidence to the many foreign communities in the ports up and down the

China coast. Gunboat diplomacy is out of fashion today, but in those

days many a Western trader in China was very glad to see the White

Ensign or the Stars and Stripes flying on a warship in the harbour.

"In 1937 I graduated to my first destroyer, the Defender, on the China station. With her 35,000 HP and 32 knots, she was a very different proposition from my little 785-ton Kingfisher

and her 20 knots. I thanked my stars for my early destroyer training in

the old Mediterranean days as the flotilla streaked about the China

Sea, performing its intricate manoeuvres at 30 knots. But this soon

came to an end with the beginning of the war between Japan and China,

when every ship on the station was required to bring comfort and

confidence to the many foreign communities in the ports up and down the

China coast. Gunboat diplomacy is out of fashion today, but in those

days many a Western trader in China was very glad to see the White

Ensign or the Stars and Stripes flying on a warship in the harbour.

The Munich crisis found Defender

playing guardian angel to the foreign community of Amoy and the

precarious position in which they would have found themselves in the

event of war must have been brought home by our immediate departure for

our war station at Singapore. But I was not to take Defender to war, and in the spring of 1939 I handed her over to my successor and sailed for home.

I hoped that when the buff envelope from the Admiralty arrived with my

next appointment it would give me command of one of the new destroyers

joining the fleet. It was not much cause for jubilation therefore when

mobilisation of the Reserve Fleet was ordered and I was instructed to

go to Rosyth to commission a destroyer veteran of the 1914-18 war, HMS Venomous.

A destroyer is a destroyer though, I told myself resignedly, and set

off. My gloom returned when I reached Rosyth and sought out from

amongst the mass of ancient-looking V and W class destroyers lying in

the dockyard basin the particular old warrior that had been selected

for me.

I found that Venomous was a

very dubious proposition. Built towards the end of the 1914-18 war, she

had been equipped with an experimental machinery layout. For those of

an engineering bent I will enlarge by saying that she was the first

destroyer to be given a "closed-feed system”. The system was

experimental and had a number of defects; so, when the First World War

came to an end Venomous was hurriedly placed in reserve - and her engineers no doubt breathed a heavy sigh of relief.

In consequence I found that, unlike her sister ships, she had never

been out of reserve since; that engineers, used either to more modern

or more matured types of machinery, viewed her hybrid set with

considerable alarm; and that none of the improvements by way of

modernisation that had been given to others of her class had been given

to her. This meant amongst other things that she had not been fitted

with the asdic, the only device for detecting submerged submarines.

With her obsolete armament of 4-inch guns, no anti-submarine weapon and

very doubtful machinery, she recalled the Duke of Wellington's scathing

description of some troops under his command which "might not frighten

the enemy but, by God, they frighten me”.

However, we duly commissioned and a ship's company composed largely of

experienced, time-expired reservists who 'knew the ropes' got things

smoothly into shape. Smoke began to pour from the funnels, machinery

came to reluctant life, giving the ship that vibration which is its

soul, and in due time we nosed our way out into the Firth of Forth for

trials and exercises.

HMS Venomous exercising with the16th Destroyer Flotilla in August 1939

Written on reverse of the centre photograph: "91 RD. 90 degree turn to port. 16th DF Manoeuvres, Aug 1939"

Courtesy of Erica Pountney and Angela Bowley, the daughters of Eric Pountney, the photographer

These

went off surprisingly well owing to my engineer officer's skilful

manipulation of his strange machinery system, and we became part of the

flotilla commanded by Captain Tom Halsey in the Malcolm.

Our first assignment was to take part in the royal review of the

Reserve Fleet in Weymouth Bay, the principal function of which was the

presentation to His Majesty of all commanding officers and a selected

number of officers and men from each ship. When my turn came I

particularly noticed the glowering, surly face of Admiral Darlan, head

of the French Navy, who had been invited to be present. At that time I

had no idea that he had such an implacable hatred for the Royal Navy,

but looking back it seems to me that he made no attempt on that

occasion to hide his feelings.

From Weymouth the flotilla went to its war station at Portsmouth and it was there that we heard Neville Chamberlain announce that we were at war with Germany.

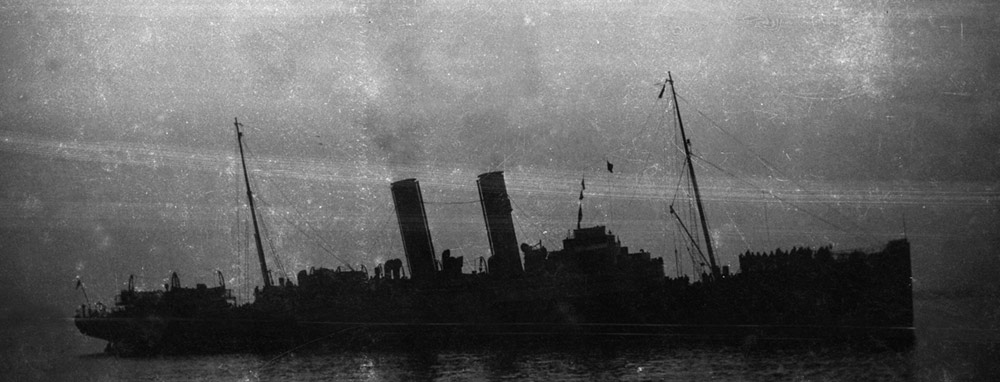

The LNER passenger ferry, Archangel, was one of the ships which carried troops of the BEF from Southampton to France - note troops on the bow

She carried troops back from

France at the end of the Great War but did not survive this war - she

was bombed on the 16 May 1941 and abandoned after being beached

The photograph was taken by Eric Pountney, a wireless telegrapher on HMS Venomous

The flotilla's function was to escort the ships carrying our troops across to France - and a very unrewarding task it turned out to be. Nightly, at around midnight, two or three ships of the flotilla would rendezvous, at the ‘gate' of the boom which stretched across to the Isle of Wight, with the fast cross-Channel or Harwich packet boats which were employed as troopships. Having marshalled them into a body outside the boom, we would set off at a spanking 25 knots for Cherbourg or Le Havre where we would arrive at daylight. We usually had an hour or two to wait before bringing back an empty convoy and could sometimes get ashore for a brief shopping tour - Guerlain's perfume for our girl friends, and wine, were the only purchases I can remember. The former made us very popular ashore on our return and the latter soon gave Venomous a remarkably fine cellar for a modest price.

It

was difficult to take our escorting duties very seriously for the enemy

made no effort to interfere with these nightly runs. The chief

difficulty I found was to cope with the rather hectic 'phoney war'

conditions ashore (where I had just got to know the girl whom I later

married), and then to take my ship out of harbour in the black-out and

the rain and thread my way between the very dim lights marking the gate

of the boom defences. With the fierce cross-tide at the gate it took

some tricky manoeuvring to wait while the troopships went through.

Once outside and round the Nab Tower this convoy of fast ships would

hare slap across the main convoy route up the channel, showing no

lights and of course without radar in those days. On at least one

occasion we ran at right angles through a large convoy at 25 knots and

it was a miracle that there were no collisions. It was all good

practice for the problems of wartime navigation, which stood me in good

stead later, but I felt a fraud in my old Venomous - our chief pre-occupation was to keep up with our high-speed charges, let alone to protect them.

It was therefore with some excitement that I found the familiar

official envelope containing a new appointment in my mail one morning

early in January. Opening it I found that I was to command HMS Hearty,

then in process of completion at Messrs Thorneycrofts shipyard at

Woolston, near Southampton. The name of the ship meant little to me and

it sounded more like a tugboat than anything, so it was a happy

surprise when I found she was in fact a destroyer much like our own H

class, though modified to suit the tastes of the Brazilians for whose

navy she and five others were being built.

Turning Venomous over to my

relief, John MacBeath, I hurried off to Thorneycrofts and there, lying

at her buoys, I saw the ship that I knew I could lose my heart to. To

try to explain this feeling would be as tedious as those passages of a

novel in which the author describes the beauty of his heroine, so I

will restrict myself to saying that she was a destroyer built on

classical lines by Thorneycrofts, who are in my opinion the finest

destroyer constructors in the world. But even the most attractive of

heroines cannot be without flaw and Hearty

had early faults to get over. These were chiefly due to her completion

date being arbitrarily advanced by order of the Admiralty who were

desperate to get ships to sea where there was a deadly shortage of

craft to hunt the U-boats and escort our convoys. However, steam

trials, gunnery trials and all the multifarious tests and calibrations

required before formally commissioning went off well, and soon I had

signed the receipt on behalf of the Admiralty for ‘one destroyer’. We

were ready for our first assignment: to test her out for teething

troubles."

Donald Macintyre's story is continued on the website of the V & W Destroyer Association. HMS Hearty was renamed Hesperus on 27 February 1940, after the Hesperus of mythology, to avoid confusion with the destroyer Hardy. HMS Hesperus was based at Sheerness as Leader of the 21st Destroyer Flotilla which included HMS Vanessa. Ken Brown served in Vanessa and described events on the V & W Destroyer Association's website.

Donald Macintyre was CO of HMS Walker in March 1941 when three of Germany's top u-boat aces were sunk in a week and Otto Kretschmer was captured and landed by HMS Walker at Liverpool. This story is told by Paul Smith the grandson of George Smith, the Wireless Operator. In August 1944 Ron Rendle was on the bridge of HMS Bickerton with Macintyre when Bickerton was torpedoed. Ron Rendle was 98 when he died on the 23 December 2017.

A HARD FOUGHT SHIP:

the story of HMS Venomous

by R.J. Moore and J.A. Rodgaard

Holywell House Publishing, 9 May 2017

244x170 mm with 480 pp, 256 photographs and 12 maps and plans

ISBN 978-0-9559382-4-5; hardback, £35 (including post & packaging)

A small number of author signed copies are available - first come first served