Les

Proctor grew up in Watford, lived in Garston and got to know the

Fighting Cocks, England's oldest pub, and the local of Bill Forster, the publisher of A Hard Fought Ship (2017) and writer of this introduction to Les Proctor's story of the sinking

of HMS Hecla and his rescue by HMS Venomous.

Les had wanted to join the Royal Navy since he was eleven and as a first step to becoming an Electrical Artificer

(EA) he took a job at the General Electric

Company at Wembley in 1937 to train as an Instrument Maker Improver. This was declared a "reserved occupation" and the Royal Navy

refused to take him when he tried to enlist on his eighteenth

birthday after the war started in 1939. He was only able to fulfill his

ambition and join the Royal Navy in June 1941 when he was 19 and had

changed his job to a non reserved occupation as an Instrument Maker at

Novabax Ltd.

After basic training at HMS Victory (Gosport and Portsmouth) and a six months electrical course at HMS Vernon (formerly Roedean College, Brighton, a girls school) and St Dunstans (a former home for the blind) he was drafted to HMS Hecla after its return from Iceland for a refit on the Clyde at Glasgow.

Events on the voyage south leading to Hecla being mined near Cape Town on the 15 May 1942 and spending five months under repair in drydock at Simonstown are described elsewhere on this web site. In October 1942 HMS Hecla

left Simonstown with Capt G.V.B. Faulkner RN in command to

support the Anglo-American invasion of North Africa, Operation Torch.

With help from Linda Clarke and his daughter Kathleen Ladouceur Les Proctor described what happened when HMS Hecla was torpedoed, in Chapters 2 and 3 of a self published spiral bound booklet My Experiences in the Royal Navy 1939-1946. This extract begins when the first torpedoes struck.

"At 23:30 on the 11 November when we were 35

degrees N, 9 degrees 55' W and approximately 150 miles from Gibraltar

we were hit by two torpedoes simultaneously. Cyril Hardware and I were

awake but in our hammocks and his only comment was "not again" (a

reference to us being mined). While we scrambled out and dressed a

sleepy head appeared from the only other hammock in the mess and

"Porky" Jennings asked why we were getting up! We went to action

stations and found that the boiler rooms had been hit and we were

without engines or power, and the ship had a large list. The diesel

generators, located in the engine room, were run up and power restored.

Pumps, etc. were activated and the ship was brought back on an even

keel.

HMS Vindictive passed us a

line to prepare for towing. Meanwhile, the EAs were frantically

restoring power to various services and some of us were in the engine

room operating circuit breakers. The engine room was on the hold deck,

approximately 20 feet below the water line. Also present were a rotund

stoker Petty Officer and a couple of stokers. Access to the engine room

was via a manhole hatch, oval in shape, held down by six clamps, and

not easy to access at any time.

At 00:22 on the 12th, while we were working at the far end of the engine room, another

"fish" came in for'ard and, despite the climb up a 20 foot ladder to

get through the hatch, we were all out within a minute, or so it

seemed. The stoker Petty Officer always had a squeeze to get through

the hatch but he went through with lifebelt and gas mask like a cork

out of a bottle.

Again the ship listed and two more "fish" came in at 00:32 and 01:05

but we (EAs) carried on running emergency cables connected to terminals

through the bulkhead at the deckhead. We started at the supply end and

connected live (220V DC) but as the ship took on a 45-degree list, we

eventually worked with one foot on the ship's side and the other on the

deck. When we had connected about half-way through the ship, an

Engineer Officer came by and said that "abandon ship" had been given

some time ago, it seems at approximately 00:15. Our Chief EA and the

Warrant Electrician plus a watchkeeper were at the switchboard, so I

went down to warn them and then joined Cyril on deck.

"Stepping In" 01:09

The drill for leaving a sinking ship is to run, walk or slide down the

high side to avoid being dragged under as the vessel rolls, so we made

for the high side. Discarding our boots and jackets, we went to the

rail but we both fell and slid down the wet deck. On the way, I hit the

legs of Flynn who was trying to work his way up. However, we all

finished up in a heap on the rail, which was then under water. Cyril

stood at the rail and ceremoniously dumped his cap and we all (Cyril

Hardware, Flynn, Allan Wardell, and myself) "stepped in" and started to

swim (my watch stopped at 01:09), agreeing to stay together. It was

pitch dark and there was a ten-foot swell so we could not see each

other but we saw the Marne by

the light of a star shell she sent up. We tried to keep in touch by

calling out but we were all being sick from taking in salt water and

fuel oil, and the last I heard was Alan Wardle saying he could not go

on. Cyril had said we ought to swim to the Marne,

a quarter of a mile away, but she received a "fish" in the stern and

the explosion doubled us up and showered us with debris. Cyril and I

both instinctively ducked our heads under water to avoid the chunks of

steel plate coming down. The Admiralty report states that a second

torpedo, presumably aimed at the Marne, missed, and hit Hecla. As we were still close to Hecla and a quarter mile from Marne,

we should have been affected by a second explosion seconds later, but I

only remember one explosion. As we did not wish to be caught between

two sinking ships, we turned and swam at ninety degrees. As it

happened, the Marne did not sink and was towed to Gibraltar the next day. Before being hit she had picked up about fifty survivors.

I swam on and found a Spanner raft, a cross hatch of wood about 18

inches square, but lost it soon after when another swimmer grabbed it.

I swam until dawn, about 07:00, when I saw a Carley float and hung onto

the ropes around it. They were made for 12 but this had many more and

was just submerged. After a while it overturned and, for a time, I sat

on it until it overturned again. As people died or disappeared, I

managed to stay with it and we helped to balance it against the

ten-foot swell. As the light improved, we caught glimpses of Venomous

picking up survivors but it was around noon before they got to us. This

was one of the worst parts of our time in the water as we had no way of

knowing whether the rescuer would ever come our way. All we could see

was the top of its masts when we rose to the top of a wave. As time

wore on the number on the float gradually reduced as cold, fatigue or

despair overcame them. The first time 1 heard the "death rattle" was stoker pensioner Tommy Totel who was then pushed away; it was depressing.

Rescue, 12:00, November 12

As the ship came alongside, we had to grab ropes or nets as she could

not stop and, thereby, present an easy target. I managed to grab the

scramble net but as my fingers, arms, and knees were locked, I could

not climb up, and two seamen reached down and hauled me aboard. Once on

deck, I could only move with bent knees. My only clothing was an

oil-soaked tropical shirt and underpants, the latter were "borrowed"

while I slept and they were drying.

Venomous ceased looking for survivors at 12:50 as no more could be seen and she was running low on fuel oil.

Questions were asked about the recovery of bodies. Venomous would have been a sitting target if it had stopped to retrieve bodies,

consequently, to avoid leaving them floating, they were machine gunned

to make them sink. I understand that the last survivors were picked up

some 23 miles from the point of sinking, i.e. a drift of about two

miles per hour.

A hero of the rescue was Herbert Button, the anti-submarine bosun of HMS Venomous,

who entered the water several times to assist exhausted survivors. He

became exhausted, retired to his bunk, lapsed into a coma and died a

few days later.

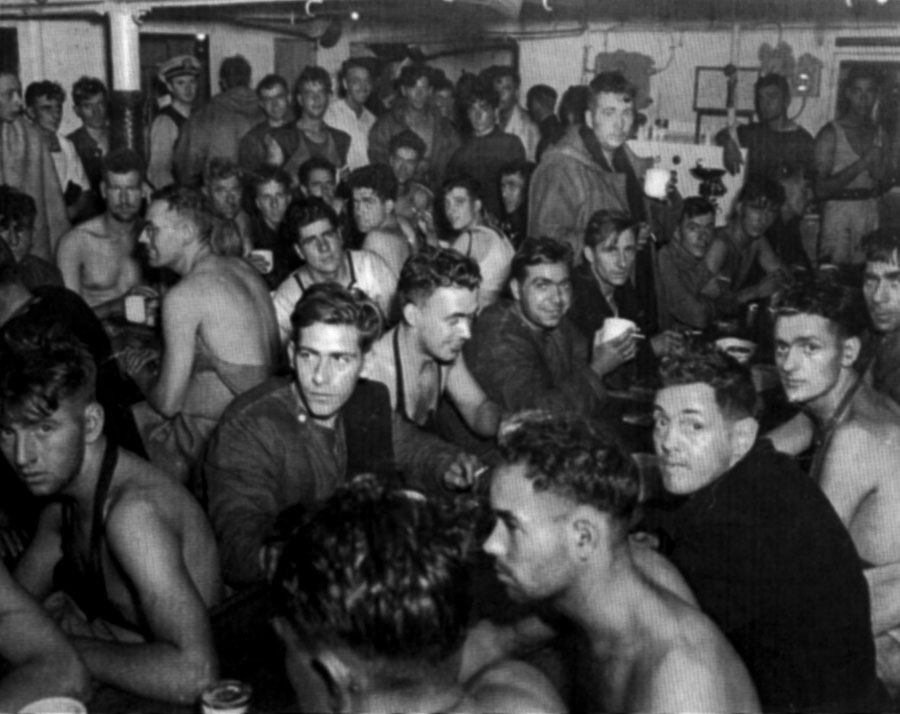

Venomous had a crew of 120 and picked up about 500 survivors, so you

can imagine we each had a stateroom! We were so crowded and tired, we

stayed where we were. The only person I recognised was a pensioner,

Charlie Meech, with whom I worked in the instrument section. You could

set the clock by him: workshop 08:00, tea 10:00, rum 11:00, leave for

dinner 11:50, head down 12:15, workshop 13:15, to "secure" at 15:50.

When Hecla sank, he abandoned

ship fully clothed, got on a Carley float and was picked up early. When

I saw him he was still fully clothed including collar, tie, and a cap,

dried out, and his only complaint was that his tobacco had gotten wet.

He had lost his entire watchmakers' equipment (the value in 1940 was

150 pounds for the lathe alone) but not a word about that.

Conditions aboard the rescue ship

As we were near the end of a two week voyage, there was little food

aboard so we could not be fed. Fuel oil was also low and, as we were

closer to Casablanca than to Gibraltar, we went there to take on fuel.

During the night passage, a spread of torpedoes was fired at us but,

fortunately, these were spotted and the spread "combed", i.e. the ship

turned to go between them.

We stretched out on the mess benches to sleep with the first fellow on

his back with his head at the end. Others then lay between his legs

resting their body on his stomach - this were the soft sleeping

accommodations. Due to the numbers, many had to sleep on the deck. When

the torpedo attack came during the night, the violent turn shot us all

onto the deck on top of those sleeping there. The crockery also smashed

on the deck. The lower mess deck is below the waterline and, had we

been hit, those in there would have had no hope, but those of us at

upper deck level may have escaped.

Arriving in Casablanca around 07:30 with only about four tons of fuel left (gauges showed empty), we were taken aboard the heavy cruiser, USS Augusta and given food and some clothing. I got a pair of socks, underpants, and drill trousers, after having been dressed in only my oil-soaked tropical shirt. That food tasted very good after 36 hours without. The landings in that area had just taken place and there was still fighting in the town and there were ships in the harbour on fire or sunk.

After refuelling we set out around noon. Outside the harbour

destroyers were circling, dropping depth charges and, as we crossed the

circle, a huge mushroom of oil came up following one depth charge drop.

The U-boat was hit.

Passage to England

We arrived in Gibraltar late evening and went to our respective messes on board HMS Duke of York

and "crashed" down on the deck. The following morning they gave us

their breakfast - bacon, eggs, and tomatoes - the first eggs these

people had received in three months. This was our first food in 24

hours. As we were heading for our mid-day meal at 12:00 we were piped

to muster on deck where we boarded tugs to go out to vessels for

passage back to England. We steamed around until 19:30, going from ship

to ship, until the liner Reina de Pacifico

agreed to take us. One vessel said we could come aboard but we would be

two decks below the Lascar messes, around bottom decks. This was

rejected. Once aboard the Reina de Pacifico we were allocated to cabins, between eight and twelve to each, but we received some food, our first since breakfast.

We sailed at midnight and, as the anchor was weighed, it banged on the

ship's side. One of us, a South African called Sjolander, was out of

his bunk, on deck, found the cause and back in the cabin before we

could get out - he had become very nervous.

Next day a raffle was held for a USAF bomber jacket (leather, lambswool

lined). Jennings won this with a shilling he "borrowed" from me (I

still have the belt in which I saved my money), so I bought it from him

for 30/- (£1 and ten shillings). I kept it until the late 1970s when I

gave it to Arve Bredahl, a friend in Saskatchewan.

Interestingly, Jennings, who had left the Hecla

in the prescribed manner by sliding down the higher side, found that

his buttocks and forearm had been badly lacerated by the barnacles but

the salt water had cauterized the cuts and stopped the bleeding."

HMS Hecla on the Clyde after commissioning in March 1941

Bill Clayton survived the Hecla to serve on its identical sister ship, HMS Tyne

Courtesy of Simon Skelhorne

The Reina del Pacifico

berthed at Greenock on the 23 November and after walking barefoot over

cobblestones to a bombed out warehouse, they

were partly kitted up (Les was given a seaman's jersey, boots, a cap

and an oilskin coat). They were given a stew for dinner at noon and,

when the nearby "Wrennery" heard they had nothing more, sandwiches and

cocoa were brought at 21.00. They boarded a train at midnight for the

journey south to their barracks at Portsmouth.

*****

When Les returned from leave in January 1943 he was drafted to HMS Indomitable at Liverpool, an Illustrious

Class aircraft carrier commanded by P. Wooten-Wooten, known as "Peanuts" and other less polite names (he was not a

popular officer). After working up routines they left the Clyde in June

for the Mediterranean to cover the landings in Sicilly and Indomitable survived a hit from an air launched torpedo and spent ten days in Malta being "patched" before proceeding to Gibraltar. The Indomitable was sent to the US for repairs while Les returned to Londonderry on a corvette, his first experience of

life at sea on one of the smaller ships of the Royal Navy.

Les was posted to John Brown's shipyard, Clydebank, in October 1943 to

standby for the final building and commissioning of the aircraft carrier

HMS Indefatigable and it was there that he met and courted his wife, Catherine Macfarlane. Indefatigable joined the home fleet at Scapa Flow and took part in the attack on the Tirpitz in Altenfjord.

On 18 November HMS Indefatigable sailed

to join the British Pacific Fleet at Trincomalee in Ceylon where they

went on three week sorties to bomb oil fields on the Japanese occupied

islands of the Dutch East Indies. Indefatigable

spent Christmas in Australia and then joined the US Fifth Task Force in

covering the landings at Okinawa and

Sakashima

"during which they were repeatedly attacked by Japanese torpedo bombers

and kamikaze (suicide bombers)." One of these at Okinawa "scored a hit

on the flight deck at the base of the island, blowing a hole right

through but fortunately not damaging the boiler room smokestack. After

the islands were taken we withdrew to the Philippines, Manila Bay, and

effected our own repairs."

On 18 November HMS Indefatigable sailed

to join the British Pacific Fleet at Trincomalee in Ceylon where they

went on three week sorties to bomb oil fields on the Japanese occupied

islands of the Dutch East Indies. Indefatigable

spent Christmas in Australia and then joined the US Fifth Task Force in

covering the landings at Okinawa and

Sakashima

"during which they were repeatedly attacked by Japanese torpedo bombers

and kamikaze (suicide bombers)." One of these at Okinawa "scored a hit

on the flight deck at the base of the island, blowing a hole right

through but fortunately not damaging the boiler room smokestack. After

the islands were taken we withdrew to the Philippines, Manila Bay, and

effected our own repairs."

They patrolled the Japanese coast and

Formosa "while the atom bombs were delivered" and when Japan

surrendered "went into Tokyo Bay for the signing ... and met up with

HMS Duke of York carrying Admiral Tovey to accept the surrender on Britain's behalf and our captain sent a message to the skipper of the Duke of York 'Well done - we do the work, you take the glory'." Indefatigable

flew the flag in Australia and New Zealand and returned to Portsmouth

via Cape Town in March 1946 where it was decommissioned.

After

demobilisation Les returned to his pre-war job at Novabax, an unhappy

experience. His three children were born in Watford but Les moved to

Canada in 1955, obtained a job as an electrical engineer and the family

joined him the following year. His daughter, Kathy, lives in Ottowa and

visited him regularly. His oldest daughter, Valerie, lives in

Geneva and Douglas, the youngest member of the family, in Calgary.

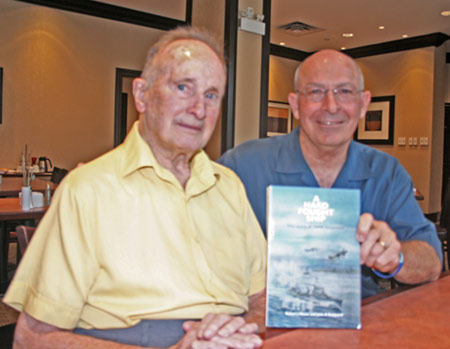

In August 2012 Capt John Rodgaard USN (Ret), the author of A Hard Fought Ship,

visited Les in Ottowa and presented him with a copy of his book.

Armistice Day 2012 was the 70th anniversary of the torpedoing of

HMS Hecla when 273 men died and HMS Venomous rescued 493 of the survivors. Les Proctor lived a good life and was 94 when he passed away on 9 September 2016.