This vivid description of the torpedoing of the destroyer depot ship, HMS Hecla,

off the coast of North Africa shortly before midnight on the 11

November 1942 and the rescue of five hundred survivors the following day was written

in 1951 by "Freddo" Thomas, the RDF Operator, who joined Venomous

in June 1940 after Dunkirk and remained aboard until October 1943. It

was originally published in the annual booklet of the London Nautical

School where he taught after the war while studying part time at

LSE.

In

July 2009 he wrote to the publisher that "by then [1942] we

were a team of two in the Radar compartment, the highest point in the

ship, and during the strains of the action we were able to relieve each

other on an agreed basis as it was not possible to follow the usual

four hour watch system" (personal letter).

His account does contain a few errors, some of which are typing errors. I have inserted corrections within square brackets rather than change what "Freddo" has written. The photographs were all supplied by him and were mostly taken on his Ensign box camera.

The

warm sunshine bathed the rock and the harbour nestling below.

Occasionally a golden gleam, coming from the face of the rock marked

the windscreen of a turning car climbing the twisting road. Gibraltar

Harbour seemed to be more crowded with warships than usual, while the

commercial harbour contained a vast array of vessels of all kinds. It

was November 1942 and the great battle that had been ranging for a

fortnight in the Western Desert was over and Rommel was in full

retreat. It did seem at last that someone at last had beaten Rommel

and, looking round the Harbour at the Naval might assembled there, we

wondered what was to be the next move.

During the first dog-watch our sailing orders came aboard. “Being in all respects ready for sea, HMS Venomous

will proceed at 2300” went the familiar Naval prose. As soon as we were

clear of the harbour, with the lights of Algeciras twinkling on our

Starboard beam, the Captain spoke to the ships company over the

internal relay system. We were about to take part in Operation Torch,

which called for simultaneous Anglo-American landings in French North

Africa on the morning of 8 November. A pre-requisite for the success of

the operation was the quick capture of the three large ports. Algiers,

Oran and Casablanca. Our part in Operation Torch was to meet at sea two large depot ships, HMS Hecla and HMS Vindictive which were to be the base ships at Algiers and Oran, and in company with destroyer HMS Marne, to escort them safely to their respective ports. Obviously this was an important though not spectacular role in Torch,

and quite likely to be uneventful. But the Captain warned us that after

the initial landings on the 8 November, every U-boat in the

Mediterranean and Eastern Atlantic would be whistled up to attack our

convoy.

The two depot ships had already sailed from Capetown a week previously and we were to rendezvous with them near the Canaries.

On the 8 November in the Forenoon, we met the depot ships coming from

the south. The two destroyers then turned about, stationed themselves

one on either side and proceeded northwards towards the Strait of

Gibraltar. The large convoy and its heavy escort (of which the two

depot ships had been a part) soon drew ahead of us and disappeared. We

continued our more leisurely course, the two big ships with their

escorts. The Hecla we knew

well from the earlier days of the war in the North Atlantic when she

had been the depot ship at Havelfjord, Iceland. We had often gone

alongside Hecla and she had

provided us with fresh provisions, delicious white bread, cinema shows

and skilled technicians to deal with our engine room defects.

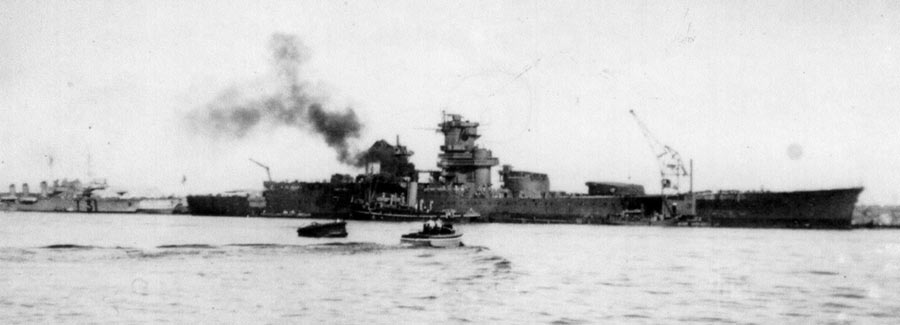

HMS Hecla (left) and HMS Marne (right) at Havelfjord, Iceland, in 1941

Courtesy of the estate of F.N.G. Thomas

HMS Marne was a brand new destroyer we had not encountered previously, and we in Venomous felt rather shabby and outdated in our 24 year old ship.

Later

that day we listened to the first BBC news of the landings. The British

landings at Algiers and Oran had succeeded after initial set backs, but

the Americans seemed to be making slower progress at Casablanca.

Meanwhile, we moved northwards at a moderate speed as we were timed to

arrive about five days after the first landings. We felt comfortably

detached from the sterner business going on at the ports, but were very

much on our guard. Obviously two destroyers provided a very incomplete

anti-submarine screen and the enemy had been attacking in "wolf packs".

By 11 November we were level with Casablanca about forty miles out. We

wondered how the American landing was going, the news that day had

mentioned that a French battleship in the dockyard was offering

strenuous resistance to the Americans. We were too far away to see

anything.

At about 2330 hrs there were two bright flashes from the Hecla

followed by a heavy explosion. Almost simultaneously the radar and

asdic cabinets were calling the bridge, Radar reported the decreasing

size of the echo from Hecla

and the Asdic reported a submerged echo at about 2,000 yards on our

port bow. Immediately we altered course to intercept what was almost

certainly a U-boat. Within a minute we were, steaming at full speed,

thanks to our closed-feed system. Radar then reported a surface target

dead ahead. Evidently the enemy had surfaced. When the range had closed

sufficiently we fired a star shell. Up went the binoculars on the

bridge. The flare burned brightly, and almost under our bows, it

seemed, was the U-boat, like a monstrous black whale its wet side

glistening in the yellow light.

"Stand by to ram". Everyone on the bridge held tightly to some firm

object and braced for the shock. The U-boat however, could turn in a

tighter circle and was too quick for us. She was clear with ten yards

to spare, and her guns crew were already training their five-incher on

us. Neither of our four-point-sevens could bear as we reeled to port

under full helm. A quick-witted seaman on our starboard Oerlikon opened

fire and the enemy gun crew melted under the murderous hail. Still

reeling crazily to port, we came round again for another run in and the

U-boat was diving at panic speed. Once again she managed to evade our

cleaving bows, but as we raced by we fired a pattern of depth charges,

one actually striking the submerging conning tower.

Astern the sea shuddered, boiled and upheaved itself into a gigantic

water spout. By the light of our ten inch searchlight we saw a huge,

black cigar shape appear to break slowly into two, both parts slowly

disappearing almost immediately.

Meanwhile, the other destroyer had stopped to pick up survivors from the Hecla. There were about eight hundred men in the oil-covered water. With scrambling-nets down and all hands manning the sides Marne

had picked up about one hundred men when her stern was completely blown

off by a torpedo but miraculously her watertight bulkheads held and she

remained afloat, a helpless hulk, waiting for the next crashing blow

which would send her to the bottom of the Atlantic.

The old Venomous was now left with the triple task of protecting the helpless Marne,

picking up about seven hundred men and at the same time fighting off

the wolf pack already closing in for the kill. Each one of these tasks

clashed with the other two. We no longer had the freedom of dashing

after radar and Asdic contacts, for this would leave the Marne

unprotected, and we could not depth charge freely because of our men in

the water. Somehow we had to pick these men up out of the sea and that

would mean stopping and presenting ourselves as an easy target for the

U-boats. The other depot ship meantime had relieved us of yet a fourth

task by quitting the scene at high speed. This was no place for a large

vessel to dally.

Having completed half-a-dozen sweeps around the crippled destroyer, Venomous made

for the men in the water, whose position was revealed by hundreds of

minute, bobbing lifebelt lights. Soon we had our scrambling nets down

and all men who could be sparred were manning the sides. As we wallowed

in the heavy swell, over the side they came, black and slippery with

oil often by their hair, vomiting and coughing up the filthy oil. Most

were hurried to the warmth of the mess decks, while those suffering

acutely from exposure were taken to the blazing heat of the ship’s

galley.

Reports were now coming from the asdic and radar of suspicious contacts, but the floating wreckage from the Hecla

had been confusing the operators. Now the radar reported a definite

contact slowly closing us. Our Captain had the awful decision to make,

either to remain stationery and perhaps save another hundred men, or

get under way and attack the stalking U-boat. If we delayed too long we

should certainly be torpedoed and all would be lost but if we started

turning our screws it would certainly kill many men.

We continued picking up men for another five minutes, allowing the U-boat to close to about a thousand yards.

Then seizing the microphone, the Captain warned the men in the water

“Keep clear of the screws! I must go ahead to investigate a contact! I

must go ahead! I will come back for you! I will come back for you!”

Seeing their last chance apparently slipping away from them, several of

the men tried to cling to the ship and to the scrambling net, with

disastrous results. We had soon worked up to top speed and an audible

sigh of relief went through the ship after the terrible twenty minutes

of waiting for torpedoes out of the darkness. The asdic echo was now

loud and clear and our quarry dived. Judging ourselves to be at least a

mile from the men in the water the Captain ordered a heavy pattern of

depth-charges to be dropped, and the ship shuddered violently as eight

charges erupted a couple of hundred yards astern. Tilting over

dangerously at full helm, we swept the area with our searchlight. A

mass of oil spread like a dark stain over the surface. Asdic reported a

lost contact but to make absolutely sure we made another run over the

target area and dropped another pattern. No submarine could have

possibly lived through that,

When we returned to the crippled Marne

and the men in the water we noticed that their lights were getting more

dispersed. This would make our task more difficult and after circling

the Marne several times to

conduct a thorough anti-submarine sweep, we again stopped to pick up

survivors. Many of them were now numbed with cold and needed a great

deal of help to climb the scrambling nets. On the bridge they could do

little but wait, expecting any second to feel the crashing blow which

would end all our anxieties. We were only too painfully aware of the

easy target we presented to the enemy. It was a wonderful relief to

feel the ship get under way as once again we went to investigate a

dangerous echo. Altogether we made four depth charge attacks that night

but with inconclusive results. Between these attacks, we would make

periodic sweeps, around the Marne and then stop and pick up more men.

Survors from HMS Hecla sleeping on the deck of HMS Venomous and the burial at sea of those who died after rescue

Courtesy of the estate of F.N.G. Thomas

When dawn came we had nearly six hundred [an over estimate, the true figure was nearly five hundred] survivors from the Hecla in the Venomous, and the Marne was still there. We continued sweeping around the Marne

and picking up what few men were left alive in the water until late

afternoon, when two destroyers and a tug from Gibraltar arrived to take

charge of the Marne.

But now, after nearly twelve hours at full power, our reserves of oil fuel were. about exhausted. The Venomous,

an old "V&W" destroyer had been built in 1919 for the shorter

ranges in the North Sea. It was obvious that we had insufficient oil to

reach Gibraltar. We had tried unsuccessfully to go alongside Marne

for her oil but the ships were crashing heavily together in the swell.

The Captain then decided to make for Casablanca, about thirty miles to

the eastward.

Arriving off the port at about 1700 hours, we were challenged by the American Cruiser Augusta,

which started swinging her huge turrets to aim her guns on us in a

distinctly unfriendly way. We speedily identified ourselves and went

into the harbour, going alongside an American Carrier, to which

we transferred the Hecla survivors [they were initially taken aboard USS Augusta, issued with clothes and fed before returning to Venomous and later transferring to the USN carrier USS Chenango

where they spent the night]. About two hours later a few hundred of

them, dressed in US Navy working uniforms, were able to return to us

after a bath and a good meal. As we looked around the harbour, it was

evident that Casablanca had only been taken that very morning. The

French Battleship Jean Bart

was lying on her side with smoke and flames pouring out from an

enormous gash. Meanwhile, our sailors had taken full advantage of the

Americans' obvious greenness by trading the “famous Venomous

cap ribbons” for cartons of cigarettes. The young American sailors

fresh from the peace of the United States, stared in shocked silence

upon the ninety pitiful forms laid out under hammocks on our forecastle

[should be nine, typing error?]

Having

topped up with oil from the carrier we slipped and proceeded out of

harbour and kept up a steady twenty knots to Gibraltar. On the way we

performed the melancholy task of burying at sea all those that had died

after being picked up. On arrival at Gibraltar all the Hecla survivors went ashore to the base and we set to cleaning ship. To the great disgust of everyone, we discovered that Venomous

was duty ship that night for the Strait U-boat patrol, this meant

another sleepless night chasing radar echoes, which usually turned out

to be unlit Moorish fishing vessels.

About 0900 next morning, bleary eyed and very sorry for ourselves, we entered harbour just as the huge battleship King George V

was leaving for the United Kingdom. A magnificent line of sailors stood

at attention on the forecastle and a superb Royal Marine band played on

the quarter-deck of the great ship as she made her way towards the

harbour entrance. Coming abreast the great flagship, shabby little Venomous

had just made her salute and received the condescending reply, when the

perfect symmetry of the ranks was rudely broken by a large number of

“American” sailors who should have been decently tucked out of sight,

rushing to the guardrail in the waist of the great ship, and waving

their hands excitedly. Clear across the water came their shout, “GOOD

OLD VENOMOUS!!!”.

Up went our chins and out went our chests. Seven hundred eternally

grateful men were an awful lot of friends … someone appreciated us!

Footnote: The survivors eventually returned to the Clyde on the elderly liner, Reina del Pacifico, which had been converted into a troop carrier. Freddo was mistaken in believing the U-boat had been sunk. U-517 survived both attacks and was sank on the 9 April 1944 by US Task Group 22.3. Werner Henke, its CO, was captured and imprisoned at Fort Meade, Maryland, and shot while attempting to escape.

"Freddo" also wrote a true to life description of life on the lower deck of a wartime destroyer based on the three years he spend on HMS Venomous

as an Ordinary Seaman (OD), Able Seaman (AB) and Leading Seaman (LS)

before being sent for officer training after the landings in Sicily.

Sub Lt F.N.G. Thomas RNVR was posted to the cruiser HMS Sirius as HA Gunner in October 1944. In 1946 he was second in command of the mine sweeping trawler HMS Lord Irwin

en route to the Far East via Suez but was ordered back home when Japan

surrendered. Freddo gave a hilarious account of the problems caused when

the crew of former fishermen went ashore in Spain, got drunk and stole

some policemen's helmets leading to their arrest by Spanish soldiers

to the immense annoyance of the British Consul.

After the war Freddo taught at a school in north London before joining the staff of

the London Nautical School. He studied part time at the London School of

Economics for a degree and an MSc on Portsmouth and Gosport: the Historical Geography of a Naval Port

(his supervisor was so impressed he wanted him to re-register for a PhD but family commitments made this impossible) and was

appointed as Principal

Lecturer in Geography at the College of All Saints, a teacher training

college, now part of London University, and retired in 1981 as a

Reader. He married Violet Gilham in 1951 and they had two daughters. He died after a short illness on the 9 May 2012.

Return to the "Home Page" for HMS Hecla

to read the stories of some of the survivors

The story of HMS Venomous is told by Bob Moore and Captain John Rodgaard USN (Ret) in

A Hard Fought Ship

Buy the new hardback edition online for £35 post free in the UK

Take a look at the Contents Page and List of Illustrations